Cluster Munition Monitor 2023

The Impact

This overview details the negative impact caused by use of cluster munitions, and charts the efforts and challenges facing States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions that have a responsibility for clearing cluster munition remnants and assisting victims of these weapons.[1] It assesses progress on the strategic commitments made by States Parties under the five-year Lausanne Action Plan, adopted at the convention’s Second Review Conference in September 2021.[2] It also considers States Parties’ overarching commitment “to put an end for all time to the suffering and casualties caused by cluster munitions” as stated in the convention’s preamble.

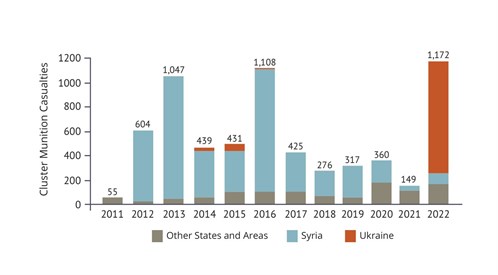

A Rise in Annual Cluster Munition Casualties

The Monitor recorded a total of 1,172 new cluster munition casualties across eight countries in 2022.[3] This is the highest annual number of people killed and injured by cluster munitions that the Cluster Munition Monitor has recorded since it first began reporting in 2010. The alarming finding is primarily due to the casualties caused by Russia’s repeated use of cluster munitions across Ukraine. Ukrainian forces have also used cluster munitions causing civilian deaths and injuries. Both states have launched cluster munition attacks that have affected protected civilian objects including schools and hospitals, and caused casualties among children. The rise is also due to cluster munition attacks in Syria during 2022, and a substantial increase in the number of casualties from cluster munition remnants in Yemen.

In 2022, 95% of cluster munition casualties recorded by the Monitor were civilians. This shows how these weapons disproportionately cause civilian harm and suffering. The devastating humanitarian impact of cluster munitions is due to their inherently indiscriminate nature. It was grave concern over civilian harm from use of cluster munitions that drove the adoption of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2008.

Of all casualties recorded in 2022, a total of 987 were caused by cluster munition attacks while 185 resulted from cluster munition remnants. Casualties directly from cluster munition attacks were recorded in three countries during 2022: Myanmar (for the first time), Syria, and Ukraine. Previously, 2021, had been the first year since 2012 in which no casualties from cluster munition attacks were recorded. The annual casualty total for cluster munition remnants in 2022 marks a significant increase from the 149 casualties recorded in 2021.

Of the 916 cluster munition casualties recorded in Ukraine during 2022, 890 were due to cluster munition attacks, though many casualties from other attacks could have gone unrecorded.[4] The remaining 26 casualties were from cluster munition remnants. Ukraine has now overtaken Syria in terms of annual casualties from cluster munitions. Previously, Syria repeatedly experienced the highest annual casualty total of any country, each year from 2012 to 2021.

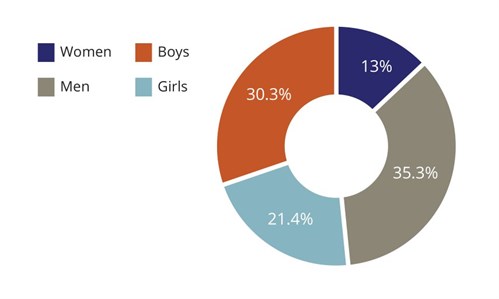

Children remain most susceptible to the threat of cluster munition remnants. They accounted for 71% of all cluster munition casualties in 2022, where the age was recorded. Men and boys made up 73% of cluster munition remnants casualties, where the sex was recorded.

Progress in Clearing Cluster Munition Remnants

In 2022 and in the first half of 2023, there were some positive developments as many countries picked up the pace of clearance efforts. Clearance of cluster munition remnants returned to the pre-COVID-19 rate after slowing amid the pandemic, yet challenges remain. The longer-term socio-economic impacts of the pandemic have affected state budgets and, in some cases, changed funding priorities. Global insecurity and ongoing hostilities hampered progress toward a cluster munition free world, especially in Ukraine.

During 2022, no States Parties completed clearance of cluster munition remnants, as required by Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Ten States Parties are still contaminated by cluster munition remnants; while two signatories, 14 non-signatories, and three other areas have, or are believed to have, areas containing cluster munition remnants.

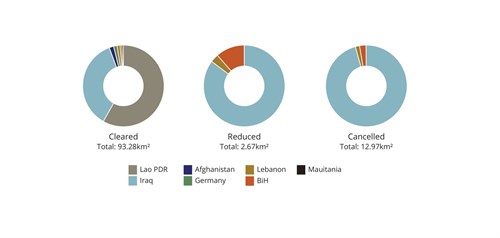

States Parties reported that 109.55km² of cluster munition contaminated land was released via clearance, technical survey, and non-technical survey during 2022, with at least 75,779 cluster munition remnants destroyed. These were primarily unexploded submunitions, also known as bomblets. Of the total land released, 93.28km2 was cleared, marking a significant increase from the 61km² cleared in 2021. Mauritania and Somalia did not report cluster munition clearance figures for 2022. No clearance took place in Chad or Chile in 2022. Chile conducted technical survey of its contaminated areas during 2021 and planned to begin clearance in 2023.[5] Chad planned to survey its remaining contamination between 2022 and 2024.[6]

Requests by States Parties to extend Article 4 clearance deadlines have been made every year since the first extension requests were submitted in 2019. In September 2022, States Parties granted Article 4 deadline extensions to Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, and Chile.[7] In the first half of 2023, Iraq submitted a request to extend its deadline by five years to November 2028, while Mauritania requested a two-year extension to August 2026.[8] Both requests will be considered at the Eleventh Meeting of States Parties in Geneva in September 2023.

Only one State Party, Somalia, is still working towards its original ten-year clearance deadline under Article 4. However, unfortunately, Somalia does not appear to be on target to meet it.

Risk Education to Respond to Increased Risk Taking-Behavior

In 2022, the socio-economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic remained a trigger for risk-taking behavior—especially from men and boys—in contaminated areas, as people were forced to rely on harmful coping mechanisms such as scrap metal collection and entering hazardous areas for precarious employment or to forage foodstuff to try to supplement diminishing livelihoods.

This was particularly apparent in Lao PDR and Lebanon.[9]

All affected States Parties have a risk education mechanism in place, with the exception of Germany, where the cluster munition contaminated area is on military land that is inaccessible to the public.[10] Of the contaminated States Parties, Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia reported implementing risk education activities during 2022, and where funding was available, restored field activities after forced interruption due to the pandemic.

Challenges of Providing Adequate Assistance to Victims

Victim assistance is a core legal obligation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, yet States Parties with survivors face an array of challenges in meeting it.

Under Article 5, the convention codifies an international understanding of victim assistance and its components that extends on the scope and understanding of the victim assistance norm developed under the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty.[11] That standard was again adapted, although in a less comprehensive form, in the text of the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[12] Most recently, in November 2022, 83 countries meeting in Dublin adopted the Political Declaration on Strengthening the Protection of Civilians from the Humanitarian Consequences Arising from the Use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas.[13]

Aspects of the 2022 political declaration on explosive weapons overlap with, and may bolster implementation of, the provisions of the Convention on Cluster Munitions related to victim assistance. The declarationrefers to “blast and fragmentation effects” that “cause deaths and injuries, including lifelong disabilities,” and includes the specific commitment to “provide, facilitate, or support assistance to victims.”[14] The declaration’s signatories have agreed to collect and publicly share disaggregated data on the effects of use of explosive weapons in populated areas; facilitate humanitarian access to those in need; adopt a gender-sensitive and non-discriminatory approach to providing assistance; take into account the rights of persons with disabilities; and facilitate the work of organizations protecting and assisting impacted civilian populations.

Victim assistance efforts under the Convention on Cluster Munitions face numerous challenges. In 2022, many States Parties continued to depend on dwindling international support for victim assistance. Afghanistan and Lebanon faced drastic economic crises that have impaired the functioning of their healthcare systems. In States Parties such as BiH, Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Lao PDR, and Somalia, local and international partners continue their work to fill major gaps in the availability, accessibility, and sustainability of healthcare and rehabilitation services. There was limited progress in 2022 in access to socio-economic inclusion programs and in the provision of financial assistance to victims. There were new psychological support initiatives, yet peer-to-peer support remained lacking despite the recognized need for workable local services.

Assessing the Impact

Cluster munition casualties

Global Cluster Munition Casualties

As of the end of 2022, the total number of cluster munition casualties recorded by the Monitor globally for all time reached 24,274. This total includes casualties resulting both directly from cluster munition attacks (5,662) and from unexploded cluster munition remnants (18,611).[15] Monitor casualty data starts in the mid-1960s, when the United States (US) used cluster bombs extensively in Southeast Asia.

As many casualties go unrecorded, global cluster munition casualties may be as high as 56,600; a figure calculated from a review of multiple datasets and individual country estimates.[16]

Before the adoption of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2008, a total of 13,306 cluster munition casualties had been identified globally.[17] Since then, the total number of recorded casualties has increased as new surveys have identified more pre-convention casualties and new casualties from historical cluster munition remnants, as well as due to new cluster munition attacks and further casualties from the remnants they left behind.

As of the end of 2022, cluster munition casualties have been recorded in 15 States Parties to the convention, four signatory states, 18 non-signatories, and three other areas. The first confirmed cluster munition casualties in non-signatory Myanmar were recorded in 2022.

The states with the highest number of casualties, for all time, in the Monitor dataset are: Lao PDR (7,802), Syria (4,408), Iraq (3,175), Vietnam (2,135), and Ukraine (1,016). Before 2022, Ukraine had less than 100 recorded cluster munition casualties, from previous use of the weapons in 2014–2015 and the resulting contamination.

States and other areas with cluster munition casualties (as of 31 December 2022)[18]

|

More than 1,000 casualties |

100–1,000 casualties |

10–99 casualties |

Less than 10 casualties/unknown |

|

Iraq Lao PDR Syria Ukraine Vietnam |

Afghanistan Angola Azerbaijan BiH Cambodia Croatia DRC Eritrea Ethiopia Kosovo Kuwait Lebanon Russia Serbia South Sudan Western Sahara Yemen |

Albania Colombia Georgia Israel Myanmar Nagorno-Karabakh Sierra Leone Sudan Tajikistan Uganda |

Chad Guinea-Bissau Liberia Libya Mauritania Montenegro Mozambique Somalia

|

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; and other areas are in italics.

Among the 15 States Parties with recorded cluster munition casualties, 13 have a recognized responsibility for victims under the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Colombia and Mozambique have had cluster munition casualties reported, but have not recognized having any victims and therefore a responsibility to assist victims under the convention.[19]

In its Article 7 transparency reports for the convention, Colombia noted no reports or records on victims of cluster munitions. However, in November 2017, the Supreme Court of Colombia upheld a decision of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) in the case “Santo Domingo Massacre vs. the Republic of Colombia” regarding redress for victims of a cluster munition attack in Santo Domingo, Colombia in 1998. As identified in the case, 17 civilians were killed and 27 were injured.[20]

There were reported to have been casualties from cluster munition remnants in Mozambique, though these were not distinguished from explosive remnants of war (ERW) in the data.[21] Mozambique also reported that there might be military cluster munition victims assisted by the Ministry of Defence, but that information was protected by state secrecy protocols. After previously reiterating that “additional surveys are needed to identify victims of cluster munitions,” Mozambique reported in 2019 that “at the moment there is no evidence of victims of cluster munitions.”[22]

The majority of recorded cluster munition casualties for all time (54%, or 13,146) occurred in States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

A total of 604 casualties have been recorded in signatories Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Liberia, and Uganda.

In non-signatory states, a total of 10,107 cluster munition casualties were recorded for all time up to the end of 2022. Since the convention’s entry into force in August 2010, casualties from cluster munition attacks have only occurred in non-signatory states, namely Azerbaijan, Libya, Myanmar, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

In other areas where cluster munition casualties have occurred—Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara—a total of 417 casualties were recorded for all time.

Cluster Munition Casualties in 2022

The Monitor recorded a total of 1,172 cluster munition casualties during 2022 across eight countries, including three States Parties and five non-signatories.[23] This is the highest number of annual casualties recorded since 2010 when the convention entered into force.[24]

Cluster munition attacks accounted for 987 casualties in Myanmar, Syria, and Ukraine in 2022, of which the vast majority (890) were in Ukraine. This contributed significantly to the increase in casualties from 2021, which was the first year in a decade that no new casualties from cluster munition attacks were recorded.

Cluster munition casualties in Syria, Ukraine, and all other states and areas 2011–2022[25]

Cluster munition remnants pose an ongoing threat and disproportionately harm civilians, with children particularly at risk from unexploded submunitions. In 2022, a total of 185 casualties were recorded from cluster munition remnants globally, with 50 people killed and 134 injured. For one casualty their survival was not reported. This represents an increase from 149 casualties caused by cluster munition remnants in 2021. However, the total for 2022 is likely far higher, as there was a notable absence of data collection and sharing on casualties from cluster munition remnants in Syria and Ukraine during 2022.

Limited access to conflict-affected areas, a lack of available data due to insufficient resources, and inconsistency in reporting mean that comparisons between recorded annual casualty totals do not necessarily represent definitive trends. Casualty data is adjusted by the Monitor over time when new information becomes available.

Cluster munition casualties in 2022

|

Country |

Casualties |

||

|

Cluster munition attacks |

|||

|

Ukraine |

890 |

||

|

Syria |

84 |

||

|

Myanmar |

13 |

||

|

Cluster munition remnants |

|||

|

Yemen |

95 |

||

|

Iraq |

41 |

||

|

Ukraine |

26 |

||

|

Lao PDR |

9 |

||

|

Syria |

6 |

||

|

Lebanon |

5 |

||

|

Azerbaijan |

3 |

||

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold.

Casualties from cluster munition attacks in 2022

In Myanmar, cluster bomb remnants were found after an aerial attack by Myanmar government forces that wounded 13 civilians in Mindat township, Chin state in July 2022.[26]

In Syria, cluster munition rockets fired by Syrian government forces, with Russian support, struck refugee camps west of Idlib city on 6 November 2022.[27] Nine civilians were killed, including a pregnant woman who died of her injuries along with her unborn child a week after the attack. Children killed in the attacks included a 14-year-old girl, two girls under six years old, and a four-month-old boy. At least 75 other people were injured.[28]

In Ukraine, the Monitor recorded at least 916 casualties from cluster munition attacks since the Russian invasion began on 24 February 2022. Access to disaggregated data on casualties has proven challenging as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) records casualties of “explosive weapons with wide area effects” without separately identifying casualties from cluster munitions. Data compiled by the Monitor indicates that at least 890 casualties (294 killed and 596 injured) were reported during cluster munition attacks in Ukraine. While this data does not yet represent a full or precise account, it clearly indicates the massive human impact of cluster munition use in Ukraine. The casualties recorded by the Monitor in 2022 as occurring during cluster munition attacks could be differentiated by date or timeframe, the location, and other identifying details.[29]

Casualties from Cluster Munition Remnants in 2022

In 2022, the number of annual casualties caused by cluster munition remnants increased in Iraq, Ukraine, and Yemen.

Yemen recorded a steep increase to 95 casualties in 2022. This is up from 29 in 2021 and 11 in 2020. In 2022, it was reported that overall casualties due to conflict in Yemen had reduced sharply since a truce began in October 2021, but that “the number of people injured or killed by landmines and unexploded ordnance remained the same or higher, highlighting the dangers of these remnants of war even in peace time.”[30]

Iraq reported 41 cluster munition remnants casualties in 2022, up from 33 in 2021 and 31 in 2020. This marked the highest annual total recorded in Iraq since 2010.

In Ukraine, 26 cluster munition remnants casualties were recorded, including 23 civilians and three clearance personnel. No cluster munition remnants casualties had been recorded in 2021.

Other countries saw the number of new annual casualties from cluster munition remnants fall. In Syria, six casualties were recorded, down from 37 in 2021. Lao PDR recorded nine casualties in 2022, a significant fall from 30 in 2021. In Lebanon, five casualties were recorded in 2022, down from eight in 2021. Four of the casualties in Lebanon in 2022 were Syrians.

In Azerbaijan, three casualties from unexploded submunitions were recorded in 2022, up from one in 2021.

Cluster Munition Casualty Demographics

Civilians accounted for 94.5% (1,109) of all casualties recorded during 2022, where the status was recorded.[31] At least 60 casualties were military personnel. Three casualties were deminers. The high ratio of civilian casualties from cluster munitions in 2022 corresponds with findings based on analysis of historical data. This consistent and foreseeable disproportionate impact on civilians is due to the indiscriminate nature of these weapons. Fewer details on demographics were reported for casualties that occurred during cluster munition attacks than for those caused by cluster munition remnants.

In 2022, the proportion of child casualties from cluster munition remnants continued to rise, accounting for 71% where the age was known.[32] Children had accounted for two-thirds (66%) of cluster munition remnants casualties in 2021 and 44% in 2020. In 2022, children accounted for the majority of casualties from cluster munition remnants in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen. All five casualties from remnants in Lebanon during 2022 were boys.

Of all child casualties of cluster munition remnants in 2022, where the sex was known, 61% were boys and 39% were girls.[33]

Where the sex was known, 31% of cluster munition remnants casualties in 2022 were recorded as female. Of these, 81% were girls and 19% were women. Among the remaining 69% of casualties recorded as male, 57% were boys and 43% were men.

In 2022, survival outcomes differed depending on the sex of casualties: 41% of female cluster munition remnants casualties were killed compared to 32% of male casualties. Previously, in 2021, the reverse was observed, with 47% of male casualties killed compared to 26% of female casualties. This had also represented a reversal of the overall situation reported in 2020, when half of female casualties were killed.

Contamination from Cluster Munition Remnants

Global Contamination

A total of 26 states and three other areas are known or suspected to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants as of 1 August 2023. Ten are States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and have clearance obligations, while two are signatories. Fourteen non-signatories and three other areas are also affected by cluster munitions. The number of states and areas listed by the Monitor as contaminated or affected by cluster munition remnants remained unchanged from 2021.

Estimated cluster munition remnants contamination (as of 31 December 2022)[34]

|

Massive (more than 1,000km2) |

Large (100–1,000km2) |

Medium (10–99km2) |

Small (less than 10km2) |

Unknown |

|

Lao PDR Vietnam |

Cambodia Iraq

|

Azerbaijan Chad Chile Mauritania Nagorno-Karabakh Syria Ukraine Yemen

|

Afghanistan BiH DRC Georgia Germany Iran Kosovo Lebanon Libya Serbia South Sudan Sudan Tajikistan Western Sahara |

Angola Armenia Somalia

|

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; and other areas are in italics.

Cluster Munition Remnants Contamination in States Parties

States Parties that have Completed Clearance

Under Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under their jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention.

No States Parties reported completion of clearance of cluster munition remnants during 2022. The last States Parties to complete clearance were Croatia and Montenegro, in 2020.

In all, a total of 10 States Parties have reported completing clearance of cluster munition remnants as required by the convention.[35]

States Parties that have completed clearance of cluster munition remnants

|

State Party |

Year of completion |

|

Albania |

2009 |

|

Croatia |

2020 |

|

Grenada |

2012 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

2008 |

|

Montenegro |

2020 |

|

Mozambique |

2016 |

|

Norway |

2013 |

|

Palau |

2010 |

|

Republic of the Congo |

2012 |

|

Zambia |

2010 |

Extent of Contamination in States Parties

The Convention on Cluster Munitions, as well as Action 18 of the Lausanne Action Plan, requires States Parties to identify the precise location, scope, and extent of cluster munition remnants contamination in areas under their jurisdiction or control. The Lausanne Action Plan also requires contaminated States Parties to establish accurate, evidence-based contamination baselines, to the fullest extent possible, no later than the Tenth Meeting of States Parties in 2022, or within two years after entry into force of the convention for new States Parties.

As of the end of 2022, five States Parties—BiH, Chile, Germany, Iraq, and Lebanon—had a clear understanding of their contamination having conducted evidence-based surveys, while survey was ongoing in Lao PDR.[36]

In BiH, cluster munition remnants contamination is primarily a result of the 1992–1995 conflict in the former Yugoslavia.[37] In May 2023, BiH reported that 0.35km2 of land was still contaminated by cluster munition remnants.[38]

In Chile, contamination from cluster munition remnants is limited to land that was used for military training, on an army base and three ranges belonging to the Chilean Air Force.[39] Cluster munition remnants contamination across the four sites totals 30.77km².[40] In 2022, Chile did not release any cluster munition contaminated land. Chile has been granted a deadline extension under Article 4 to clear its remaining contamination from 2023–2026.[41]

In Germany, cluster munition remnants still contaminate a former military training site in Wittstock, located 80km northwest of Berlin.[42] In March 2023, Germany reported that 5.72km² of contaminated land has been cleared since 2017, leaving 5.28km² still to be cleared.[43]

In Iraq, the Regional Mine Action Center for the south of the country (RMAC South) reported that as of February 2023, cluster munition remnants affected a total area of 174.13km² across the four southern governates of Basrah, Missan, Muthanna, and Thi-Qar. The highest level of contamination is in Muthanna (81.78km2).[44] The RMAC in the Middle Euphrates region reported 4.48km2 of contamination, while RMAC North reported 10.99km2. Nationally, Iraq’s cluster munition remnants contamination therefore totals 189.6km2. This represents an increase of 11.46km2 on the 2021 total, due to newly discovered and surveyed contaminated areas.[45] No suspected hazardous areas (SHA) or confirmed hazardous areas (CHA) have been reported in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, which covers the governorates of Duhok, Erbil, Halabja, and Sulaymaniyah.[46]

In Lebanon, the Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) reported that as of the end of 2022, cluster munition remnants contamination totaled 5.23km² of CHA in Bekaa, Mount Lebanon, and southern Lebanon. Despite 0.44km2 of newly identified contamination, the 2022 total reported by LMAC marks a decrease of 1.04km2 since 2021, due to land release activities.[47]

Lao PDR is the State Party most heavily contaminated by cluster munition remnants. Of the country’s 18 provinces, 15 are contaminated, nine heavily.[48] As of the end of 2022, the extent of CHA in surveyed areas of Lao PDR totaled 1,745.37km² across 11 provinces.[49] Clearance operators report that at least 186 types of munitions including different types of cluster munitions have been found in Lao PDR.[50]

Afghanistan reported in April 2023 that it had a total of 9.9km2 of land contaminated by cluster munition remnants, covering 16 areas across the provinces of Faryab, Nangarhar, Paktya, and Samangan.[51] Eleven of these areas were identified by survey in 2021, and a nationwide survey to establish the full extent of contamination has been proposed. This is now possible after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, because areas of the country previously difficult to reach due to security concerns have become accessible.[52]

Chad reported in June 2021 that the last area known to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants had been cleared.[53] However, Tibesti province, in the northwest of Chad, which is suspected to contain cluster munition contamination around former Libyan military bases, had not yet been surveyed.[54] In 2022, Chad submitted an Article 4 deadline extension request, to conduct non-technical survey of 19.05km² in Tibesti until 2024. Chad plans to submit a second extension request with a workplan for clearance based on the results of non-technical survey.[55] As of June 2023, Chad had not reported any survey progress through the end of 2022.[56]

Mauritania conducted an initial assessment in 2021 that found 14.01km² of land contaminated with cluster munition remnants in the region of Tiris Zemmour in the north, bordering Western Sahara.[57] In April 2022, Mauritania reported that the contamination is across 10 areas totaling 14.01km², and consists of BLU-63 and Mk-118 submunitions.[58] Mauritania has reported that further survey is required to determine the full extent of the contamination. In early 2023, it requested a two-year extension to its Article 4 clearance deadline, to 1 August 2026.[59]

In Somalia, the extent of contamination in unknown, but believed to be limited. It may include areas contaminated with PTAB-2.5M and AO-1-SCh submunitions in Jubaland state, on the border with Kenya and Ethiopia. BL755 submunitions have also been found in the Middle Juba and Gedo regions in Jubaland state, as well as in Puntland on the border with Ethiopia.[60] There may be contamination in the Bakool and Bay regions of South West state.[61] The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported in 2021 that cluster munition remnants may also have been collected and used as components for improvised explosive devices (IEDs).[62] Somalia reports that no survey of contaminated areas has been possible, due to a lack of funding and inaccessibility amid armed conflict.[63] As of 1 August 2023, Somalia had not provided any updates on contamination.

Possible Contamination in States Parties

Colombia may have a small amount of residual contamination, though it states that no evidence has been found.[64] In 2022, Colombia did not report any contamination on its territory.[65] When the convention entered into force for Colombia in 2016 it reported that it was in the process of establishing the location and extent of any cluster munition contamination.[66] In 2017, Colombia stated that it had no cluster munition remnants contamination, yet no survey was undertaken to confirm this.[67] In 2021, a study reported that contamination was a possibility, as in the 1990s the Colombian Air Force had acquired two types of cluster bombs: the CB-250K from Chile and the ARC-32 from Israel. Yet no sufficient information on their use was available prior to ratification of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and subsequent stockpile destruction.[68]

In the United Kingdom (UK), it is estimated that more than 2,000 crates of AN-M1A1 and/or AN-M4A1 “cluster adapter” type bombs and some 800 fused cluster bombs are believed to remain in UK waters.[69] These are located at Sheerness off the east coast of England, in the cargo of a sunken World War II ship.[70] The wreck is in a no-entry exclusion zone and under constant radar surveillance. The UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency undertakes regular surveys and has reported that the wreck is showing evidence of gradual deterioration but is considered to be in a stable condition.[71]

Cluster Munition Remnants Contamination in Signatories

Two signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions—Angola and the DRC—may be contaminated by cluster munition remnants. Signatory Uganda completed clearance of its contaminated areas in 2008.[72]

Angola has not reported any areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants, but there may remain abandoned cluster munitions or cluster munition contamination. In past years, cluster munition remnants have been found and destroyed through explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) call-outs. In May 2023, Angola reported that 9,515 items of unexploded ordnance (UXO) were cleared and destroyed in 2022, but did not specify if any were cluster munition remnants.[73]

The DRC has reported a total of 0.16km² of land contaminated by cluster munition remnants. The contamination is primarily from MK7-118 and PM1 submunitions, and is located in the provinces of Equateur, Ituri, Maniema, South-Kivu, Tanganyika, and Tshopo. Contaminated areas are reportedly marked, but difficult to access. Further survey is viewed as necessary to clarify the exact extent of contamination, especially in Maniema and Tshopo provinces.[74]

Cluster Munition Remnants Contamination in Non-Signatories and Other Areas

Fourteen non-signatories and three other areas are, or are believed to be, contaminated by cluster munition remnants.

Vietnam is massively contaminated by cluster munition remnants, but there is no accurate estimate of the extent of contamination. In 2023, the Vietnam National Mine Action Center (VNMAC) told the Monitor that more than 5.6 million hectares (56,000km²) is contaminated by ERW, including cluster munition remnants. This represents more than 17% of Vietnam’s total land area. The contamination is mostly found in the central provinces of Quang Tri, Quang Binh, Ha Tinh, Nghe An, and Quang Ngai.[75]

Cambodia has raised its overall estimate of cluster munition contamination after conducting surveys. The Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA) reported in May 2023 that a total of 741.07km² is contaminated by cluster munition remnants.[76] This is an increase from the previous reported contamination of 698.69km² at the end of 2021.[77] Most of the contaminated areas are in the northeast, along the borders with Lao PDR and Vietnam.[78]

In Armenia, as of October 2022, land contaminated by ERW was estimated to total 39.24km2, of which less than 5% is believed to be due to cluster munition remnants.[79]

Azerbaijan’s extent of cluster munition contamination, in areas under its jurisdiction, was not known, due to ERW contamination in areas regained during the conflict in 2020 with Armenia that are yet to be surveyed. Casualties from cluster munition remnants continued to be reported in Azerbaijan into 2022.[80]

In Syria, cluster munitions were used extensively between 2012 and 2020, across 13 of its 14 governorates, before use appeared to drop off in 2021. However, new cluster munition use was reported in November 2022 on camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in northwest Idlib governate.[81] From 2018 to 2020, the HALO Trust conducted an initial assessment of ERW contamination in northwest Syria and reported that cluster munitions were the most frequently found type of ordnance, also accounting for the highest number of incidents.[82] In 2022, with limited capacity, the HALO Trust conducted further survey in the northwest but identified mine contaminated areas only.[83] Cluster munition contamination in Syria is believed to be significant but its exact extent remains undetermined.[84]

In Ukraine, extensive cluster munition attacks were reported in 2022 and the first half of 2023 after the Russian invasion, resulting in widespread contamination. Cluster munitions continue to be used by both parties to the conflict. The extent of contamination has not been documented but is increasing due to the ongoing use.

Yemen identified approximately 18km² of suspected cluster munition contaminated areas in 2014, before a Saudi Arabia-led coalition used cluster munitions in Yemen in 2015–2017. This reportedly increased cluster munition contamination in northwestern and central areas.[85] The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reported in 2021 that cluster munition and ERW contamination is widespread in the north.[86] In southern Yemen, a few areas are contaminated by cluster munition remnants.[87] The Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC) did not report any cluster munition contamination in 2022.[88]

In Kosovo, the Kosovo Mine Action Center (KMAC) reported 9.82km² of cluster munition remnants contamination as of the end of 2022, including 0.42km2 of newly discovered CHA.[89]

Non-signatories Georgia, Iran, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and the area of Western Sahara are known or believed to each have less than 10km² of cluster munition remnants contamination.

Georgia is thought to be free of contamination, though South Ossetia—a disputed territory not controlled by the government of Georgia—is a possible exception.

Iran’s extent of contamination from cluster munition remnants is not known. Some contamination is believed to date from the 1980–1988 Iran-Iraq war, when cluster munitions were widely used in Khuzestan and to a lesser extent in Kermanshah.[90]

Libya’s contamination from cluster munition remnants is primarily the result of armed conflict in 2011 and renewed conflict since 2014, particularly in urban areas. In 2019, there were several instances or allegations of cluster munition use by forces affiliated with the Libyan National Army (LNA).[91] The exact extent of contamination in Libya has not yet been determined.

Serbia is contaminated by cluster munition remnants in three municipalities: Bujanovac, Tutin, and Užice. Serbia reported 0.74km² of CHA as of the end of 2022.[92]

South Sudan reported a total of 5.28km² of cluster munition remnants contamination in April 2023, with 4.58km² classified as CHA and 0.7km² as SHA.[93]

Sudan reported 142,402m2 of cluster munition remnants contamination as of the end of 2021, with 5,820m² classified as CHA and 136,582m² as SHA.[94] Since conflict erupted in April 2023, Sudan has not been able to provide updated information on the extent of contamination.

Tajikistan has reported cluster munition remnants contamination totaling 2.07km² CHA.[95]

Western Sahara was reported to have 2.09km² of cluster munition remnants contamination as of the end of 2021.[96] No clearance activities took place in Western Sahara during 2022.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, a survey by the HALO Trust found that 68% of inhabited settlements had experienced cluster munition use and contamination. The current extent of contamination is not known, but is believed to total less than 16km2.[97]

Addressing the Impact

Cluster Munition Remnants Clearance

Obligations Regarding Clearance

Under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, each State Party is obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under their jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention.

Clearance in States Parties in 2022

Monitor data on cluster munition remnants clearance in States Parties is based on information from sources including reporting by national mine action programs, Article 7 transparency reports, and Article 4 extension requests.[98]

In 2022, seven States Parties reported having released a combined total of 109.55km² of cluster munition contaminated land, of which 93.28km2 was cleared. A total of 75,779 cluster munition remnants—mostly unexploded submunitions and unexploded bomblets—were destroyed.

The clearance total for 2022 represents a significant increase on the 61.07km² reported cleared in 2021. Afghanistan, BiH, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania all reported clearing more land in 2022 than in 2021. Iraq and Lao PDR accounted for more than 94% (some 30km2) of the total annual increase in the area cleared. Both Afghanistan and Iraq significantly increased their clearance rate compared to 2021.

Cluster munition remnants clearance in 2021–2022[99]

|

State Party |

2021 |

2022 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

Cluster munition remnants destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

Cluster munition remnants destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

0.42 |

32 |

1.59 |

1,197 |

|

BiH |

0.62 |

2,995 |

0.64 |

1,599 |

|

Chad* |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chile |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Germany |

0.85 |

466 |

1.34 |

1,187 |

|

Iraq |

10.16 |

8,202 |

33.62 |

4,670 |

|

Lao PDR |

47.84 |

66,921 |

54.37 |

64,516 |

|

Lebanon |

1.00 |

2,418 |

1.15 |

2,556 |

|

Mauritania |

0.18 |

7 |

0.57 |

N/R |

|

Somalia |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

TOTAL |

61.07 |

81,043 |

93.28 |

75,725 |

Note: CMR=cluster munition remnants; N/R=not reported.

*Chad reported 0.41km2 cleared for the period September 2020–April 2021, but did not specify how much of this clearance took place in 2021.

Cluster munition remnants land release in 2022

Of the cluster munition contaminated land released by States Parties in 2022, 85% was cleared, 3% was reduced through technical survey, and 12% was cancelled via non-technical survey.

Only BiH, Iraq, and Lebanon reported on land release methodologies other than clearance, with Iraq accounting for 85% of the total land released through technical survey and 96% of the land released through non-technical survey.

Afghanistan reported that during 2022, 1.37km² of land with mixed contamination (including cluster munition remnants) and 0.22km2 contaminated only by cluster munition remnants was cleared, resulting in the destruction of 1,197 submunitions.[100]

BiH reported that 1.32km² of cluster munition contaminated land was released in 2022, while 1,599 cluster munition remnants were destroyed. Of the land released, 0.64km2 was cleared.[101]

Chad did not report any survey or clearance of areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants in 2022.[102]

Chile did not conduct any clearance of cluster munition remnants in 2022.[103] It plans to start clearance operations in 2023.[104]

Germany cleared 1.34km² of contaminated land during 2022, destroying 1,187 cluster munition remnants. Between 2017 and 2022, it cleared a total of 5.72km².[105]

Iraq reported clearing 33.62km² of cluster munition contaminated land in 2022, while another 15.27km² was released through survey. A total of 4,670 submunitions were destroyed in 2022, a significant decrease from 8,202 in 2021.[106] In the south of Iraq, 16.28km2 of land was cleared, while 17.34km² was cleared in the Middle Euphrates region.[107]

As in previous years, Lao PDR cleared the most land of any affected country, accounting for 58% of all reported clearance. Lao PDR cleared 49.84km2 of agricultural land and 4.53km2 of land needed for development.[108] In total, 64,570 cluster munition remnants were destroyed in Lao PDR during 2022, compared to 66,921 in 2021.[109] More than 98% (53.57km²) of the total land cleared in 2022 occurred in the nine most heavily contaminated provinces.[110]

Lebanon reported releasing 1.47km² of cluster munition contaminated land during 2022, of which 1.15km² was cleared, 0.21km² was cancelled through non-technical survey, and 0.11km² was reduced through technical survey.[111] The 1.15km² cleared represents a slight increase from the 1km² cleared in 2020. A total of 2,556 cluster munition remnants were destroyed in 2022. From 2017–2022, Lebanon cleared a total of 7.25km² of land contaminated by cluster munition remnants.

Mauritania cleared 0.57km² of contaminated land during 2022 but did not report the number of cluster munition remnants destroyed.[112]

Somalia did not provide any information on its clearance of contaminated areas in 2022, and did not report any progress for 2020–2021. Survey was planned for 2023, although no further information was available as of 1 August 2023.[113]

Article 4 Clearance Deadlines and Extension Requests

If a State Party believes that it will be unable to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants on its territory within 10 years of the entr ccy into force of the convention for that country, it can request an extension to its clearance deadline under Article 4 for a period of up to five years.

Despite progress in surveying and clearing areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants, the first clearance deadline extension requests were submitted by Germany and Lao PDR in 2019. Both states received five-year extensions. More requests have been submitted by other States Parties every year since 2019.

In 2020–2021, requests to extend Article 4 clearance deadlines were granted to Afghanistan, BiH, Chile, Lebanon, and Mauritania. In 2022, Chile submitted a third extension request based on the completion of technical survey. Requests were also submitted in 2022 by BiH and Chad. In 2023, Iraq submitted its first extension request, and Mauritania submitted its second.

Status of Article 4 progress to completion

|

State Party |

Current deadline |

Extension period (no. of request) |

Original deadline |

Status |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2026 |

4 years (1st) |

1 March 2022 |

Unclear |

|

BiH |

1 September 2023 |

18 months (1st) 1 year (2nd) |

1 March 2021 |

On target |

|

Chad |

1 October 2024 |

13 months (1st) |

1 September 2023 |

Likely to submit another extension request following survey in Tibesti |

|

Chile |

1 June 2026 |

1 year (1st) 1 year (2nd) 3 years (3rd) |

1 June 2021 |

On target |

|

Germany |

1 August 2025 |

5 years (1st) |

1 August 2020 |

Expects to complete in 2025 |

|

Iraq |

1 November 2023 |

N/A |

1 November 2023 |

Requested 5-year extension until 1 November 2028 |

|

Lao PDR |

1 August 2025 |

5 years (1st) |

1 August 2020 |

Behind target |

|

Lebanon |

1 May 2026 |

5 years (1st) |

1 May 2021 |

On target* |

|

Mauritania |

1 August 2024 |

2 years (1st) |

1 August 2022 |

Requested 2-year extension until 1 August 2026 |

|

Somalia |

1 March 2026 |

N/A |

1 March 2026 |

Unknown |

Note: N/A=not applicable.

*Lebanon reported that it was on target, but that an additional year may be required to complete clearance.

The Lausanne Action Plan notes that sustained efforts are required to ensure that States Parties complete their clearance obligations as soon as possible, and within their original Article 4 deadlines. Only Somalia remains within its original deadline.

Germany, in 2019, justified its need for a five-year extension until 1 August 2025, citing slow clearance progress due to the high density of contamination and restrictions in the accessibility of the contaminated area, which is part of a natural reserve.[114] In March 2023, Germany reported that 52% (5.72km²) of the 11km² of contaminated land has been cleared, leaving 5.28km² still to be cleared. To meet its 2025 clearance deadline, Germany will have to increase its annual clearance rate from the 1.34km2 reported for 2022.[115]

Lao PDR indicated that completion of survey is its priority during its five-year extension period until 1 August 2025, with an expectation that additional time and international support will be needed.[116] Survey was ongoing in 2021 and 2022 and will form the basis for long-term planning and clearance prioritization.

Afghanistan had initially reported that it would meet its original clearance deadline of 1 March 2022, as there was a commitment from UNMAS and the US to financially support clearance operations for 10 areas.[117] However, the discovery of additional contamination and a change in donor priorities led Afghanistan to submit an extension request until March 2026, which was granted in 2021.[118] In May 2023, Afghanistan reported its “hope to release all cluster munitions sites before 1 March 2026” but said that completing clearance was dependent on funding.[119]

In 2021, Lebanon was granted an extension to complete clearance by 1 May 2026, but reported that a decrease in funding had reduced the number of teams working to clear cluster munition contaminated areas.[120] LMAC therefore planned to focus on technical survey to speed up task completion.[121] In April 2023, Lebanon reported that it was on target to meet its clearance deadline, but that it might require one extra year.[122]

Chad reported in June 2021 that it would complete its clearance by the end of July 2021, ahead of its September 2023 deadline.[123] However, in 2022, Chad submitted an extension request until 1 October 2024 to conduct non-technical survey on 19.05km² of land in Tibesti province, which is suspected to be contaminated with cluster munition remnants. The extension request was granted during the convention’s Tenth Meeting of States Parties in 2022.[124]

Chile has not made progress clearing its contaminated areas despite becoming a State Party to the convention in December 2010. In January 2020, Chile sought an extension period of five years until 2026.[125] It revised the request to a one-year interim extension in June 2020 to enable technical survey before submitting a second extension request with a clearance plan.[126] In June 2021, Chile submitted a second one-year extension request, without survey having taken place, citing a lack of resources and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.[127] Technical survey was undertaken in 2021, before Chile submitted its third extension request in April 2022 for a period of three years, to clear 30.77km² of CHA identified in the survey. Following a preparatory phase, Chile plans to begin clearance operations in 2023 and complete clearance by the 1 June 2026 deadline.[128]

Iraqreported in February 2022 that it would not be able to meet its original clearance deadline of 1 November 2023.[129] Challenges to clearance include the fact that new contaminated areas continue to be found through survey, particularly in the south.[130] In March 2023, Iraq submitted a five-year extension request until 1 November 2028.[131] The request will be considered at the convention’s Eleventh Meeting of States Parties in Geneva in September 2023.

In 2021, Mauritania was granted an Article 4 extension to complete survey and clearance by 1 August 2024.[132] In March 2022, Mauritania reported that it still needed to determine the extent of contaminated areas to confirm if it could meet this deadline.[133] In March 2023, Mauritania submitted a request for a further two-year extension, to 1 August 2026.[134] The request will be considered at the convention’s Eleventh Meeting of States Parties in September 2023.

It is unclear if Somalia will meet its clearance deadline of 1 March 2026, as it does not have an accurate picture of contamination. Somalia has no reported plan for clearance and did not report any clearance activities in 2021–2022.

Clearance in Signatory States, Non-Signatory States, and Other Areas in 2022

In 2022, clearance of cluster munition remnants was reported to the Monitor in signatory DRC, and in non-signatories Cambodia, Serbia, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, and Vietnam, as well as in other area Kosovo. More information can be found in annual country profiles on the Monitor website.

Risk Education

Obligations Regarding Risk Education

Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions states that each State Party shall “conduct risk reduction education to ensure awareness among civilians living in or around cluster munition contaminated areas of the risks posed by such remnants.” Risk education involves interventions aimed at protecting civilian populations and individuals, at the time of cluster munition use, when they fail to function as intended, and when they have been abandoned.

Risk Education for Cluster Munition Contamination

All contaminated States Parties reported conducting risk education in 2022 except for Chile and Germany, which do not regard such activities as necessary as their contaminated areas are inaccessible to the public.

In Lao PDR, risk education is specifically directed to address the risk behaviors associated with cluster munition remnants.

In other States Parties where cluster munition contamination is mixed with landmine or other ERW contamination, operators generally do not conduct risk education specific to the threat of cluster munition remnants. In Chad and Somalia, cluster munition remnants were included in risk education materials on different types of explosive ordnance.[135]

Risk Education Targeting

The Lausanne Action Plan directs States Parties to implement context-specific, tailor-made risk education activities and interventions, which prioritize at-risk populations and are sensitive to gender, age, and disability, as well as the diversity of populations in affected communities.

Risk education beneficiaries in cluster munition affected States Parties by age and sex[136]

In most States Parties contaminated by cluster munitions, the remnants are found in rural areas and directly impact people who rely on the land and natural resources for their livelihoods. Men are a particularly high-risk group due to their participation in activities that take them into contaminated areas, such as the cultivation of land, the collection of firewood and other forest products, hunting and fishing, and herding animals.

According to data provided by States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia, men represented the largest number of direct beneficiaries of risk education in 2022.

In BiH, accidents are more common in spring and autumn during agricultural work, and when people go to the forest to collect firewood. Target groups for risk education in BiH include farmers, mountaineers, hunters, people collecting wood and other natural resources, as well as migrants traveling through BiH territory.[137]

In Afghanistan, communities living near contaminated areas were targeted for risk education, as were returnees and IDPs, nomads, scrap metal collectors, aid workers, and travelers.[138]

In Iraq, the Directorate for Mine Action (DMA) implemented an intensive seasonal risk education campaign in 2022 aimed at Bedouin people in the southern governorate of Al-Muthanna, to address a rise in incidents related to livelihood activities in spring. Iraq also specifically undertook risk education in regions along the Syrian border.[139]

In Chad, nomadic communities have been identified as high-risk due to their transit through desert areas that may be contaminated.[140] Sudanese refugees in Chad were also targeted for risk education during the first half of 2023.[141]

In Lao PDR, men and boys are the most at-risk group, due to their participation in livelihood activities such as cultivation, the collection of forest products, and hunting and fishing.[142]

In Mauritania, schoolchildren, teachers, shepherds, nomads, and fisherfolk were all considered key groups for risk education.[143]

In both Lao PDR and Lebanon, economic hardship in recent years has encouraged greater risk-taking as people have tried to supplement diminishing livelihoods.[144] The collection of scrap metal and explosives remains a common practice in parts of Lao PDR and increased in Lebanon in 2022.[145]

In Lebanon, Syrian refugees remained a priority group for risk education during 2022. Several refugee camps and settlements are located close to contaminated areas, and refugees are reportedly less familiar with this contamination.[146]

In Somalia, IDPs, herders, and nomadic communities, as well as children, have been identified as at-risk groups. Herders were the primary recipients of risk education in 2022 as they moved to new pastures or areas frequently, and may therefore be unaware of contamination in their new surroundings. IDPs in Somalia were targeted for the same reason.[147]

Children, particularly boys, remain susceptible to the lure of cluster munition remnants. Living in contaminated areas, they often lack sufficient knowledge of the risks and are prone to pick up and play with explosive items. Children remained a key target group for all affected States Parties in 2022.

In Iraq, children frequently participate in livelihood activities such as shepherding, foraging, and scrap metal collection, which places them at risk.[148] Young adult men are likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors or be in high-risk occupations such as scrap metal collection, laboring, or agriculture. This group was reported to be the most difficult to reach through risk education sessions.[149] Adolescent boys were also cited as a difficult group to reach in Lao PDR.[150]

Risk education reached more women and girls in States Parties in 2022 than in 2021. Women and girls together accounted for 35% of all recorded beneficiaries across Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia.

Risk Education Delivery

Given the strong and recognized links between risk-taking behaviors, livelihoods, and vulnerability, it is vital to integrate risk education efforts into wider mine action, humanitarian, and development initiatives.

Mine action operators in Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia all reported that risk education was integrated with clearance and survey in 2022.

In Chad, operators reported that risk education was implemented through interpersonal face-to-face sessions and community focal points. Risk education activities were combined with or implemented in advance of mine action operations.[151]

Risk education was conducted in schools in Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia in 2022. In Lao PDR and Lebanon, risk education has been integrated in the school curriculum, while in Iraq the plan is for it to be integrated in 2023.

Teenagers, particularly adolescent boys, were seen as a challenging group to reach effectively through traditional risk education methodologies. World Education Laos (WEL) targeted out-of-school children, youths, and agricultural workers. It also reached speakers of ethnic minority languages via non-formal education centers, media platforms, and using youth volunteers.[152]

Training of local committees or community focal points in Iraq and Lao PDR has been used as a way to reach beneficiaries in remote communities, where local people may distrust outsiders and speak local languages.[153] The national radio station in Lao PDR continued to broadcast risk education messages in 2022.[154] The use of digital media for risk education continued to expand in Lao PDR, as well as in Iraq and Lebanon in 2022, with social media drama series, virtual reality, short videos, and text messaging among the methods used.[155]

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The longer-term social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to affect livelihoods and encourage risk-taking behaviors in affected states. The pandemic is also reported to have limited government funding available for risk education activities.

Risk Education in Signatory and Non-Signatory States

Risk education was conducted in 2022 in signatory states Angola and the DRC, and in non-signatory states Armenia, Azerbaijan, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen, as well as in other area Nagorno-Karabakh. Risk education addressed the threat posed by cluster munition remnants and other explosive remnants of war and sought to alert communities to the danger of contamination from recent or ongoing conflict.

More information can be found in annual country profiles on the Monitor website.

Victim Assistance

Obligations Regarding Victim Assistance

As stated in the preamble to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are determined “to ensure the full realisation of the rights of all cluster munition victims and recognising their inherent dignity.” The convention requires that States Parties assist all cluster munition victims in areas under their jurisdiction, and report on progress.

Specific activities to ensure adequate assistance is provided under Article 5 include:

- Collecting data and assessing the needs of cluster munition victims;

- Coordinating victim assistance programs and developing a national plan;

- Actively involving cluster munition victims in all processes that affect them;

- Providing adequate and accessible assistance, including medical care, rehabilitation, psychological support, and socio-economic inclusion;

- Providing assistance that is gender- and age-sensitive, and non-discriminatory.[156]

These activities must be implemented in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law.

Thirteen States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions have reported having responsibility for assisting cluster munition victims.

States Parties that have reported responsibility for cluster munition victims

|

Afghanistan |

|

Albania |

|

BiH |

|

Chad |

|

Croatia |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

|

Iraq |

|

Lao PDR |

|

Lebanon |

|

Mauritania |

|

Montenegro |

|

Sierra Leone |

|

Somalia |

The Lausanne Action Plan’s commitments on victim assistance largely reflect the obligations enshrined in the convention.

Action 34 of the Lausanne Action Plan commits States Parties to provide first-aid and long-term medical care to cluster munition victims, as well as to ensure victims can access adequate rehabilitation, psychological, and psychosocial support services as part of a broader public health approach. Ideally, States Parties should have a national referral mechanism and a directory of services. Victim assistance should be provided in a non-discriminatory manner, and be sensitive to gender, age, and disability.

Action 35 requires States Parties to facilitate the educational and socio-economic inclusion of cluster munition victims. Such measures may take the form of employment referrals, access to micro-finance, livelihood support, and rural development and social protection programs.

Action 37 commits States Parties to endeavor to support the training, development, and official recognition of multidisciplinary, skilled, and qualified rehabilitation professionals.

Medical Care

Medical responses for cluster munition victims include first-aid, field trauma response, emergency evacuation, transport, and immediate medical care, as well as addressing longer-term healthcare needs. However, in 2022, in many States Parties adequate medical care was not available to communities near areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants.

In Afghanistan, people living in remote areas face significant challenges accessing healthcare due to a lack of health facilities and hazardous road conditions.[157] A non-governmental organization (NGO) working in Afghanistan, EMERGENCY, maintained a network of first-aid posts and primary healthcare centers, and ran an ambulance service for isolated areas.[158]

In Lao PDR, the Ministry of Health, with support from partners WEL and the Quality of Life Association (QLA), provided medical treatment to cluster munition survivors. WEL partnered with the NRA to administer the War Victims Medical Fund, providing emergency assistance to survivors and their families, including medical expenses, transport, and funeral expenses.[159]

Lebanon is amidst a crisis in the provision of healthcare. In 2022, hospitals were forced to restrict essential health services and limit the distribution of medicine as the healthcare system deteriorated amid the ongoing economic crisis in the country.[160] The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) continued to provide first-aid training and support public hospitals.[161]

Iraq reported that no emergency medical services are available in remote areas. People injured by cluster munition remnants are evacuated by others or receive first-aid from organizations working nearby.[162] In order to increase emergency preparedness, develop capacity and improve coordination among police, community leaders, and other key providers, the ICRC launched a nationwide pilot project on mass-casualty management in 2022.[163]

Mauritania reported that the government covers the costs of medical care for cluster munition survivors, though overall financial resources are limited.[164]

Access to healthcare in Sierra Leone is constrained by distance, cost, a lack of skilled medical staff, and poor quality services. Resources are unevenly distributed with the vast majority of referral hospitals concentrated in the urban area of the capital, Freetown.[165]

Physical Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation services include physiotherapy and the provision of assistive devices such as prosthetics, orthotics, mobility aids, and wheelchairs.

In some States Parties, such as Afghanistan and Lebanon, systems that support rehabilitation have severely deteriorated due to broader national economic and political conditions. There remain significant challenges to providing adequate, accessible, and affordable rehabilitation.

In Afghanistan, the ICRC supports rehabilitation centers in seven provinces. It also provides materials, training, and technical assistance to six orthopedic workshops.[166] HI deployed an emergency mobile team in 2022 to deliver urgent physical rehabilitation and psychosocial support to persons with disabilities in rural areas of Kabul province. HI has also referred people to healthcare services.[167] The Swedish Committee for Afghanistan (SCA) commenced a new rehabilitation program in Bamyan province in 2022 and continues to provide services.[168]

In Albania, the Prosthetics Department within the Kukes Regional Hospital, located in a cluster munition contaminated area, suffers from a lack of funding, prosthetics, and staff capacity.[169]

In Chad, HI continued to partner with local rehabilitation centers to support referrals and services. Yet following the conclusion of a muti-year joint project, including HI, in 2022, rehabilitation costs were again covered by the patients themselves.[170]

In Guinea-Bissau, survivors were able to access free rehabilitation services in 2022 at the only national rehabilitation center, located in the capital, Bissau. The ICRC’s role in training staff was limited as it scaled back its support for the center.[171]

Iraq needs to improve coordination of its 23 rehabilitation centers, while financial constraints and security issues have impeded the establishment of a national referral mechanism. Female staff are employed in rehabilitation centers to provide gender-sensitive services. The ICRC’s outreach activities in Iraq have enabled victims in remote areas to obtain assistive devices and referrals for rehabilitation. The ICRC opened a physical rehabilitation center in Erbil in March 2022. It is the largest such facility in Iraq and will also service the needs of people from nearby governorates, as well as displaced persons and refugees, particularly those from Syria.[172]

There is a significant need for rehabilitation services in Lao PDR. During 2022, the Center for Medical Rehabilitation, operated jointly by the Ministry of Health and the Cooperative Orthotic and Prosthetic Enterprise (COPE), provided physical rehabilitation to 135 survivors of cluster munitions and ERW.[173] This is a significant increase from the pandemic-affected years, with 43 survivors having received rehabilitation in 2021 and just six in 2020.[174] In 2022, the NRA and COPE signed an agreement to provide mobile rehabilitation services in Houaphanh and Xieng Khouang provinces.[175] HI supported the Ministry of Health to monitor implementation of the National Rehabilitation Action Plan.[176]

A training facility for health professionals in Lao PDR opened in 2022 with support from the Okard project. The training will improve the skills of 150 doctors, nurses, and physiotherapists at the Center for Medical Rehabilitation.[177] The five-year Okard project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), was due to end in September 2022 but has been extended at no additional cost for an extra year through October 2023.[178]

Lebanon has identified a need to secure sustainable funding for victim assistance activities and the physical rehabilitation sector.[179] In 2022, the ICRC supported seven rehabilitation projects in Lebanon, including four physical rehabilitation centers, and provided assistive devices.[180]

In Mauritania, the government provided victim assistance grants to the National Humanitarian Demining Program for Development (Programme National de Déminage Humanitaire pour le Développement, PNDHD) and the National Orthopedic and Functional Rehabilitation Center (Centre National d’Orthopédie et de Réhabilitation Fonctionnelle, CNORF), where survivors can also access psychological support services.[181]

In Sierra Leone, responsibility for rehabilitation services has been gradually handed over to the government from international NGOs, including HI and the Prosthetics Outreach Foundation. Progress has been hampered by a lack of funding, a lack of prioritization for rehabilitation, and limited coordination between providers. Subsidized services and greater outreach are needed to expand access.[182] The Ministry of Health and Sanitation adopted the Assistive Technology Policy and Strategic Plan 2021–2025, which has an objective to increase national rehabilitation capacity, covering physiotherapy and prosthetics.[183]

In Somalia, provision of rehabilitation services remained challenging amid ongoing insecurity. Physical rehabilitation centers run by the Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS) in Mogadishu and in Galkayo, Puntland were supported by the Norwegian Red Cross (NRC) and the ICRC.[184]

Psychological and Psychosocial Support

Psychological support includes counselling, individual peer-to-peer support, community-based support groups, and survivor networks. Peer-to-peer support was among the least supported victim assistance activities in 2022 despite being inclusive, targeted, cost-effective, and sustainable.

Afghanistan continued to face a severe lack of funding for all victim assistance activities, including psychological support and survivor peer-to-peer support.

BiH reported that psychological and psychosocial support were available, with Red Cross and Red Crescent social workers and volunteers trained to support persons with disabilities, including survivors.[185]

In Croatia, psychosocial assistance workshops were held for survivors of explosive weapons.[186]

In Lao PDR, psychosocial support was provided to survivors by WEL during 2022. Yet overall, psychological support services remained limited.

In Lebanon, LMAC facilitated psychological support sessions alongside ITF Enhancing Human Security.[187] The ICRC provided mental health support and referred survivors to social integration initiatives.[188]

In Iraq and Sierra Leone, HI provided mental health and psychosocial support services.

Socio-Economic Inclusion and Education

Economic inclusion via vocational training, micro-credit and income-generation projects, and employment programs remained an area of great need for cluster munition victims in 2022. Access to inclusive education, and social inclusion through sport, leisure, and cultural activities were also ongoing needs.

In BiH, Lao PDR, and Lebanon, survivors received vocational training and economic support through local organizations in 2022, with international assistance. In Croatia, survivors received assistance through training, counselling, and employability workshops.[189]

In Lao PDR, survivors received vocational training and economic support from the QLA.[190]

Victim Assistance in Signatory States, Non-Signatory States, and Other Areas

Other than in States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, victim assistance services were available to some degree in most states and areas with cluster munition casualties. Mine Ban Treaty States Parties Ukraine and Yemen, which both have commitments to assist victims, did not report on assistance to cluster munition victims specifically, despite the high numbers of recent recorded casualties. Cambodia and Vietnam, which have high numbers of historical cluster munition victims, did not highlight how their programs reach cluster munition victims specifically but updated information on services available to all survivors of mines/ERW.

More information can be found in annual country profiles on the Monitor website.

Management and Coordination

Coordination, Strategies, and Planning

Clearance

Strong coordination is an important aspect of national ownership of mine action programs as it enables efficient and effective operations.

In 2022, clearance programs in eight States Parties with cluster munition contamination—Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia—were coordinated through national mine action centers. In Chile and Germany, the defense ministries are responsible for coordinating clearance as the contamination is on former military sites.

In Afghanistan, the international community has largely suspended its support to government institutions since the Taliban took power in August 2021. In February 2023, the Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) reported that it was actively coordinating mine action in the country.[191] UNMAS supports the coordination of the humanitarian mine action sector.[192]

Action 19 of the Lausanne Action Plan requires States Parties to develop evidence-based, costed, and time-bound national strategies and workplans, as part of their Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 4 commitments. As of the end of 2022, eight States Parties—Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia—had strategic plans in place. Germany had a workplan for its extension period to 2025, while Chile included a workplan for clearance in 2023–2026 in its Article 4 extension request.

In Iraq, the DMA and the Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) prepared the first integrated strategic plan for the mine action sector, the National Mine Action Strategic Plan 2022–2028, with support from the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) and UNMAS.[193] The plan was finalized and endorsed in May 2022.[194]

In Lao PDR, the national strategy, Safe Path Forward III, was updated for the period 2021–2030, and endorsed in July 2022.[195] The NRA developed a new multi-year workplan for the mine action sector covering 2022–2026.[196]

Mauritania reported in March 2023 that it has a workplan in place for 2023–2026 to fulfil its Article 4 clearance obligations.[197] Mauritania plans to strengthen the capacity of PNDHD by retraining operational staff and deminers, which will allow for the more effective conduct of non-technical and technical survey, risk education, and clearance.[198]

Three States Parties that submitted Article 4 deadline extension requests in 2022 are required, in line with Action 20 of the Lausanne Action Plan, to provide annual workplans which include projections of the amount of cluster munition contaminated land to be addressed annually.

BiH has a National Mine Action Strategy for 2018–2025, addressing contamination from both landmines and cluster munition remnants. In granting the Article 4 extension request submitted by BiH in 2022, States Parties requested a clear workplan, and information on the total extent of the contaminated area that still needs to be addressed.[199] BiH has not provided the requested workplan, as of 1 August 2023.

Chad did not include a detailed workplan in its Article 4 extension request for non-technical survey in Tibesti province.[200] States Parties granted an extension until 1 October 2024, on the expectation that a detailed workplan and budget would be provided in a subsequent extension request, if cluster munition remnants contamination is discovered.[201]

Chile included a detailed workplan for the clearance of cluster munition remnants in its Article 4 extension request, based on the findings of technical survey conducted in 2021.[202] Chile plans to begin clearance operations in 2023 and complete clearance in 2026.[203]

Risk Education

All States Parties with cluster munition contamination have a risk education mechanism in place except Chile and Germany, where the contaminated area is inaccessible to the public.[204]

In most of these States Parties, risk education programs are coordinated by the respective national mine action center. In Iraq and Lao PDR, the education ministry has a coordination role for school-based programs.[205]

Action 27 of the Lausanne Action Plan requires that States Parties develop national strategies and workplans for risk education, drawing on best practices and standards.

Risk education is included in the national mine action strategies of Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania and Somalia.[206]

As part of their operational planning, States Parties should include detailed, costed, and multi-year plans for risk education in their Article 4 clearance deadline extension requests. There is much room for improvement in this regard. In 2022, neither BiH or Chad included risk education workplans or budgets in their extension requests. Chile did not include risk education in its extension request as its contamination is located in military areas that are inaccessible to the public. In 2023, Iraq submitted a plan with its Article 4 extension request for the distribution of risk education materials, and a multi-year workplan including a budget for 2024–2039.[207] Mauritania’s extension request includes a budget for risk education but does not include a detailed workplan.[208]

Monitoring and evaluation of risk education activities was reported in several States Parties. In Afghanistan, initial assessment forms were used to measure beneficiaries’ knowledge on risks after receiving safety messages.[209] In Iraq, quality assurance of activities was conducted by the DMA.[210] In Lao PDR, a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) survey was carried out in Xieng Khouang province in 2022.[211] In Lebanon, regular KAP surveys take place.[212] In Somalia, operators used both assessment forms and KAP surveys to monitor and evaluate activities.[213]

Victim Assistance

States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims are obliged under the Convention on Cluster Munitions to develop a national plan and budget for victim assistance. Action 33 of the Lausanne Action Plan commits states to designate a national focal point, and to address the needs and rights of victims according to a measurable national plan. All States Parties with victims have a clearly designated victim assistance focal point except Croatia and Sierra Leone. In Afghanistan, the victim assistance coordination point role was divided across focal points in three relevant ministries: the Ministry of Martyrs and Disabled Affairs, the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of Public Health.