Landmine Monitor 2017

Contamination & Clearance

Ten States Parties have residual or suspected contamination: Algeria, Cameroon, Djibouti, Kuwait, Mali, Moldova, Namibia, Palau, the Philippines, and Tunisia.

Status and Key Developments[1]

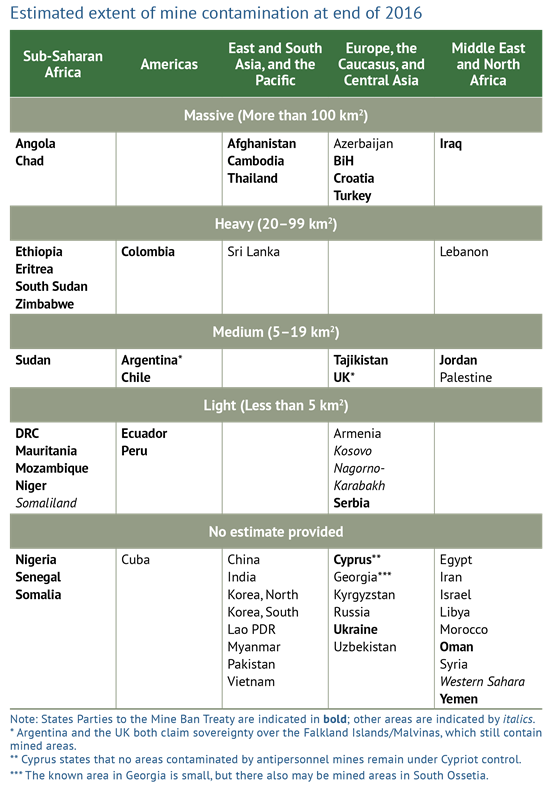

- Sixty-one states and areas have an identified threat of antipersonnel mine contamination (33 States Parties, 24 states not party, and four other areas). A further 10 States Parties have either suspected or residual antipersonnel mine contamination.

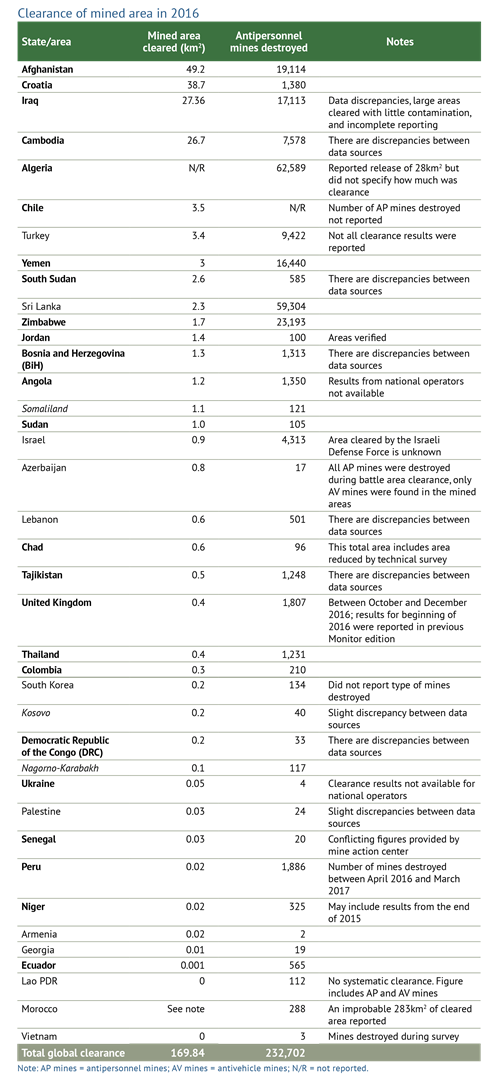

- A total of about 170km2 was reported to be cleared of landmines in 2016, the same amount as in 2015. More than 232,000 antipersonnel mines were reported to be destroyed in 2016, an increase from the 158,000 in 2015.

- New contamination in 2016 and 2017, much of which consisted of improvised mine contamination, was reported in the following States Parties: Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Ukraine, and Yemen; and in states not party: India, Libya, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, and Syria. All of these states already had contamination from previous years. There were unconfirmed reports of new antipersonnel mine contamination in Cameroon, Chad, Iran, Mali, Niger, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia

- Twenty-eight States Parties have completed implementation of Article 5 since 1999. Algeria declared completion in February 2017.[2] Mozambique, which had declared completion in 2015 but subsequently found previously unidentified antipersonnel mine contamination in 2016 and 2017, completed clearance in May 2017.[3]

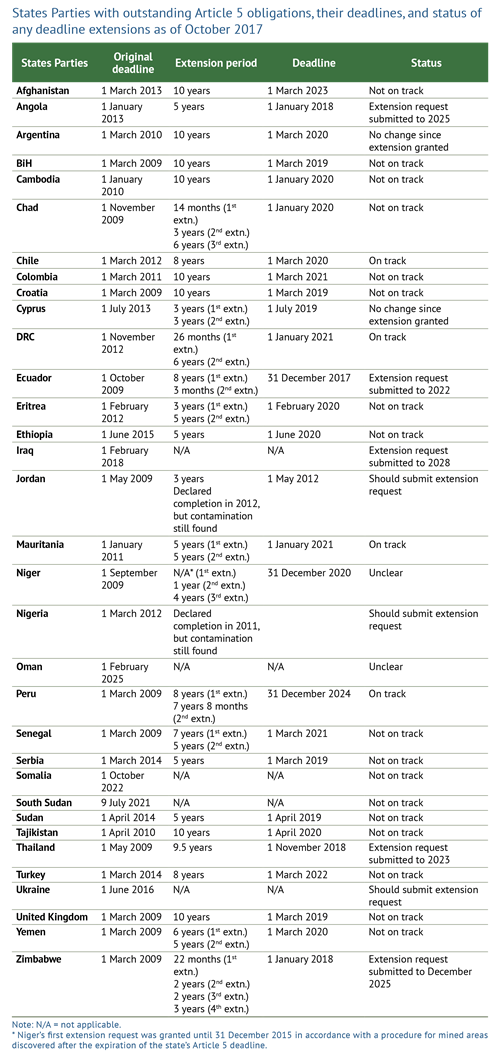

- In 2016, three States Parties submitted extension requests that were granted at the Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties: Ecuador, Niger, and Peru. Five States Parties requested extended deadlines for approval at the Sixteenth Meeting of States Parties in December 2017: Angola, Ecuador, Iraq, Thailand, and Zimbabwe.

- Ukraine is in violation of Article 5 due to missing its 1 June 2016 clearance deadline without having requested and been granted an extension.

- Jordan and Nigeria should declare that they have obligations under Article 5 and request a new deadline to complete clearance.

- Only four States Parties appear to be on track to meet their Article 5 clearance deadline: Chile, DRC, Mauritania, and Peru.

Mine Contamination in 2016

It is not possible to provide a global estimate of the total area contaminated by landmines, due to a lack of data. The extent of contamination is not known in 26 countries (seven States Parties, 19 states not party) and one other area. The global picture did not change considerably in 2016, although a number of countries, particularly States Parties, have continued to improve their knowledge of the extent of their contamination through the increased use of land release methodologies, to cancel suspected hazardous areas by non-technical survey, and to reduce confirmed hazardous areas through technical survey.

In some states, contamination increased as a result of new use of antipersonnel mines, although the extent of the new contamination—particularly by improvised mines—is not known as survey has not been conducted. There was new contamination in 2016 and/or 2017 in States Parties: Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Ukraine, and Yemen; and in states not party: India, Libya, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, and Syria. There were unconfirmed reports of new contamination in Cameroon, Chad, Iran, Mali, Niger, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia. (See the Ban Policy chapter for details.)

Several of the states for which no estimate is provided are heavily or massively contaminated. The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating North Korea and South Korea and the Civilian Control Zone (CCZ) immediately adjoining the southern boundary of the DMZ remain among the most heavily mined areas in the world, but no data is available on the extent of contamination.[4] Morocco, Myanmar, Russia, and Syria also have widespread contamination, but the extent is not known.

Ten States Parties have residual or suspected contamination: Algeria,[5] Cameroon,[6] Djibouti,[7] Kuwait,[8] Mali,[9] Moldova,[10] Namibia,[11] Palau,[12] the Philippines,[13] and Tunisia.[14]

Mine Clearance in 2016

Total global clearance of landmines in 2016 was about 170km2, with at least 232,000 antipersonnel mines destroyed. However, this is an underestimation, as some actors, such as the army, police, or commercial operators, may not systematically report clearance results. Moreover, in some states, informal clearance or community-based clearance has been conducted, which is not subject to quality management and entry into the national databases. For further details of land release results, both survey and clearance, see individual country profiles on the Monitor website.[15]

No mine clearance occurred in States Parties Ethiopia and Serbia. Only survey was conducted in Mauritania and Mozambique. In Cyprus, 0.01km2 was cleared but only antivehicle mines were found.[16] Oman reported that it cleared a mined area but did not report the size or the number and type of mines that were destroyed.[17] In Somalia, 0.04km2 was cleared but no mines or UXO were found.[18] In Western Sahara, no areas containing antipersonnel mines were cleared in 2016 east of the berm.[19]

No clearance or survey results were reported for States Parties Eritrea and Nigeria, and for states not party China, Cuba, Egypt, India, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia,[20] Syria, and Uzbekistan.

Of the 10 states that are massively contaminated with more than 100km2 of mine contamination, three reported very low clearance results of less than 1km2 in 2016: States Parties Chad and Thailand, and state not party Azerbaijan.

Improvised mines

States and other stakeholders in humanitarian demining paid particular attention in 2016 and 2017 to the increasing prevalence of improvised mines, and the specific challenges they pose to the mine action community in meeting the obligations of the Mine Ban Treaty, and in protecting civilians during or in the immediate aftermath of conflict, including emergency humanitarian crises.

An improvised explosive device (IED) is a device produced in an improvised manner incorporating explosives or noxious chemicals. IEDs that are designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person meet the definition of an antipersonnel mine.[21] They fall under the Mine Ban Treaty, therefore affected states are required to report on such contamination in their Article 7 transparency reports and to clear it in accordance with Article 5. These devices are frequently known as improvised mines.

Improvised mines are not new and have been found in many countries for decades. The countries mentioned here do not comprise an exhaustive list, so the true extent of global improvised mine contamination is probably more widespread.[22] In 2016 and 2017, large quantities of improvised mine contamination and/or numerous incidents and casualties were reported in the following States Parties: Afghanistan, Chad, Colombia, Iraq, Niger, Nigeria, Ukraine, and Yemen. In addition, improvised mines were occasionally found in the following States Parties: Algeria, Somalia, and Turkey.[23] There are unconfirmed reports of improvised antipersonnel mine use in Cameroon and Mali.

Improvised mine contamination has also been identified in the following states not party in 2016 and 2017: India, Lebanon, Libya, Pakistan, Russia, Sri Lanka, and Syria.[24]

No data exists on the extent of improvised mine contamination in any state.[25] In Afghanistan, a “preliminary survey” in 2016 identified about 220km2 of newly contaminated land affected by pressure-plate IEDs, which are landmines. This data needed further non-technical survey and had not been entered into the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) or reported in Afghanistan’s Article 7 report.[26] UNMAS/the Directorate of Mine Action (DMAC) believes the number of devices is far fewer than the number of mass-produced mines, however acknowledges that amid Afghanistan’s continuing conflict, comprehensive survey of improvised mines is impossible.[27] Colombia reports a national estimate of 51km2 of mine contamination, which is largely improvised mines, although it has yet to establish a national baseline.[28] In 2016, Iraq reported 6.67 km2 of improvised mine contamination, which is far less than the actual extent of contamination.[29]

There has been increased discussion on appropriate policies, practices, and techniques for addressing IEDs, including improvised mines. During 2016 and 2017, articles and reports have been produced regarding the issue by actors such as the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) and Mines Advisory Group (MAG), and published in the Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction.[30]

States Parties have a number of obligations with regards to improvised mines. Affected States Parties must report any confirmed or suspected improvised antipersonnel mine contamination in their Article 7 transparency reports. Resources must be made available to assess the extent of contamination and develop appropriate strategies to address it. States Parties should exchange expertise to ensure that standards are adequate for addressing improvised mines. Affected countries and donors must be prepared to cover the related costs of equipment and resources related to dealing with improvised mines, which may be higher than dealing with manufactured mines. Finally, States Parties should also monitor progress towards meeting any Article 5 obligations related to improvised mines to ensure compliance with the Mine Ban Treaty.

Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Obligations

Under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, States Parties are required to clear all antipersonnel mines as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the treaty. States Parties that consider themselves unable to complete their mine clearance obligations within the deadline may submit a request for a deadline extension of up to 10 years.

Completion of Article 5 implementation

On 10 February 2017, Algeria announced that it had completed clearance.[31]

In 2015, Mozambique declared completion of clearance, but additional contamination was found and subsequently cleared in 2016–2017.[32]

In addition, state not party Nepal and other area Taiwan have completed clearance of known mined areas since 1999. El Salvador, a State Party, completed clearance in 1994 before the Mine Ban Treaty was created.

Jordan[33] has declared completion of clearance under the Mine Ban Treaty (in 2012) but is still finding antipersonnel mine contamination and therefore does not appear in the table above. Nigeria[34] declared completion of clearance in 2011, however there have been reports of new contamination resulting from recent use of antipersonnel mines by a non-state armed group. It therefore does not appear in the table above.

Progress on meeting deadlines

As of October 2017, only four States Parties appear on track to meet their clearance deadlines, while 17 appear not to be on track, and the status of two is unclear. Five States Parties are awaiting approval of their extension requests submitted in 2017. One State Party has missed its deadline and is in violation of the treaty. Two States Parties that have declared completion in the past are still finding antipersonnel mine contamination and should request new deadlines.

The assessments of the status of each State Party regarding the fulfilment of Article 5 obligations are made through consideration of several factors, including the remaining challenge and the extent to which it is known, clearance rates, mine action capacity and assets, funding prospects, and the existence of any conflict and insecurity problems.

In 2016, three States Parties submitted requests for extended deadlines to complete their Article 5 obligations which were granted at the Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties in November 2016.

- Ecuador submitted an extension request due to unforeseen circumstances resulting from the earthquake in 2016 preventing it from meeting its deadline.[35] States Parties granted the requested three-month extension until 31 December 2017 and asked Ecuador to submit a detailed request by 31 March 2017,[36] which it did (see below).

- Niger requested until 31 December 2020 to complete survey and clearance of all mined areas.[37] In granting the request, States Parties noted that the request did not contain a detailed annual workplan with benchmarks for progress leading to completion. The meeting noted that monthly and annual projections could support Niger’s efforts in mobilizing financial and technical resources. States Parties asked Niger to provide a revised workplan by 30 April 2017, in addition to annual progress reports.[38] Niger had not submitted an updated workplan as of October 2017.

- Peru requested until 31 December 2024 to complete survey and clearance, noting the difficulties of the terrain and the acquisition of data on additional contaminated areas through information exchanges with Ecuador.[39] In granting the request, States Parties noted that improvements to its land release methodology could result in Peru proceeding with faster implementation. They asked Peru to provide by 30 April 2018 an updated workplan for the remaining period covered by the extension.[40]

In 2017, five States Parties submitted requests for extended deadlines to compete their Article 5 obligations, for approval at the Sixteenth Meeting of States Parties in December:

- Angola requested until 1 January 2025 with the goal of eliminating 1,461 mined areas.[41] The Committee on Article 5 Implementation noted that Angola did not provide annual projections of mined areas to be addressed. Angola indicated that once the dimension of the problem and its extent are more accurately identified it would be possible to plan more realistic activities, and identify the necessary resources in order the eliminate the problem.[42]

- Ecuador submitted an extension request until 31 December 2022.[43] Ecuador stated that it was requesting an additional five years to clear the remaining 0.1km2 of mined areas because mechanical assets cannot be used in these areas and operating conditions are very challenging.[44]

- Iraq submitted an extension request until 1 February 2028.[45] The ICBL noted that it is understandable that Iraq has submitted a request for 10 years due to the magnitude of contamination and security challenges. However, it stated, “As has been done for other States Parties in the past, we recommend that Iraq be granted only the amount of time necessary to prepare a plan...A shorter extension period would enable Iraq to better assess the scale of contamination once it is possible to access areas that are currently inaccessible, before presenting a long-term plan.”[46]

- Thailand submitted an extension request until 1 November 2023 to complete survey and clearance of all mined areas.[47] As of July 2017, Thailand had 409.73km2 remaining to be addressed.[48] It expects that up to 86.5% may be cancelled through non-technical survey.[49]

- Zimbabwe submitted an extension request until December 2025 to complete survey and clearance of all mined areas.[50] The Committee on Article 5 Implementation noted that the request contained an updated workplan with milestones to be met over the course of the extension period.[51] Zimbabwe stated that an eight-year National Mine Action Plan was in the process of being finalized and, once approved, would be provided as an annex to the extension request.[52]

Ukraine is in violation of Article 5 for missing its 1 June 2016 clearance deadline. The Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties expressed serious concern that Ukraine is in a situation of non-compliance with Article 5. It called on Ukraine to submit as soon as possible a request for extension, and it welcomed the commitment by Ukraine to continue to engage with the Committee on Article 5 Implementation.[53] At the intersessional meetings in June 2017, Ukraine said that it would start implementing Article 5 once the integrity of the whole territory is restored.[54] As of October 2017, Ukraine had still not submitted an extension request.

Monitoring the progress of States Parties against their Article 5 obligations and the Maputo Action Plan

In the Maputo Action Plan, adopted at the Third Review Conference on 27 June 2014, States Parties agreed to “intensify their efforts to complete their respective time-bound obligations with the urgency that the completion work requires.”[55] Actions #8, #9, and #11 relate to clearance.

The Committee on Article 5 Implementation presented its preliminary observations at the intersessional meetings in June 2017, reporting on 25 States Parties that had submitted information by that date.[56]

The assessment of progress under the Maputo Action Plan is drawn from both the committee’s observations and Landmine Monitor’s review of the progress of States Parties.

Maputo Action Plan Action #8: quantification and qualification of remaining contamination challenge

Almost all States Parties need to improve the quantification and qualification of the remaining contamination challenge. Only four States Parties have a clear understanding of the remaining contamination: Chile, Ecuador, Mauritania, and the UK. Twelve States Parties have a good knowledge of the locations of confirmed and suspected contamination but survey is needed to clarify the actual extent of contamination within those areas: Angola, BiH, Croatia, Cyprus, Jordan, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, and Zimbabwe. Thirteen States Parties have reported on known contaminated areas, but do not have a complete picture of the extent of contamination, as there are areas that have not been surveyed: Afghanistan, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Niger, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Ukraine, and Yemen. In addition, DRC may have contaminated areas that have not yet been identified. Eritrea has not provided an update on estimated extent of contamination since the end of 2013. Two States Parties have not formally reported the locations of any mined areas, Nigeria and Oman.

The committee assessed the degree of clarity of the remaining challenge, finding that only 10 of the 25 States Parties assessed had provided a high degree of clarity in their reporting: Afghanistan, Angola, Cyprus, Mauritania, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Zimbabwe. This compared to seven of 17 States Parties in 2015.

Maputo Action Plan Action #9: application of land release methodologies

Afghanistan and Angola are in the process of conducting nationwide surveys. In Angola, this has resulted in the cancellation of, on average, 90% of suspected contaminated areas.[57] Five States Parties used non-technical survey in 2016 to cancel large amounts of suspected mined area, and thus greatly decrease their estimate of remaining contamination: Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Thailand, and South Sudan. Non-technical and technical survey were also used to better define the extent of contamination in Afghanistan, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus, DRC, Ecuador, Iraq, Mauritania, Peru, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, the UK, and Zimbabwe. In 2016, Jordan was in the process of verifying areas for missing mines.[58] Colombia’s strategic plan for 2016–2021 aims to establish a national baseline of contamination.[59]

In Somalia, no nationwide survey has been conducted, mainly due to the security situation.[60] Continuous conflict in Yemen since March 2015 has prevented systematic survey.

In Chile and Niger, no survey was conducted, only clearance.[61] Ethiopia did not conduct survey or systematic clearance.[62] No survey or clearance was conducted in Serbia in 2016.[63] Four other States Parties did not report any results of land release or confirmation of mined areas through survey in 2016: Cameroon, Eritrea, Nigeria, and Oman.

Turkey did not report the results of its comprehensive desk assessment of minefield records of the eastern and Syrian borders conducted in 2016.[64] Algeria reported the release of 28km2, but did not specify how much was cleared and how much was released through survey.[65]

Almost all States Parties that implemented systematic mine clearance programs in 2016 used land release methodologies (survey and clearance), although the degree to which they were aligned with International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) varies. The committee called on States Parties to align their national mine action standards with the revised IMAS, if they have not already done so.[66]

Maputo Action Plan Action #11: on-time submission of high-quality requests

In 2017, five states submitted requests on time: Angola, Ecuador, Iraq, Thailand, and Zimbabwe.

The level of quality of the requests varied greatly. All five requests included information on progress made so far, and some form of political commitment to complete the task of mine clearance. Some lacked the key components that would characterize high-quality requests: consistent data, detailed plans for land release activities during the extension period, and milestones to measure progress.

The extension request process in 2017 demonstrated the value of exchanges between requesting states, the Committee on Article 5 implementation, and other stakeholders. Indeed, all requesting states submitted either revised requests or additional information in the course of the process, some of which was of significantly improved quality.

Jordan, Nigeria, and Ukraine should submit extension requests to address the contamination that has been identified, either new or previously existing, after they declared completion of clearance or after their deadline has passed.

Maputo Action Plan Action #25: annual submission of high-quality and updated information

As of October 2017, Article 7 transparency reports for 2016 were still outstanding for four mine-contaminated States Parties: Eritrea, Nigeria, Niger, and Somalia. Twelve were outstanding in the same month of 2016.

(See the table “Clearance of mined area in 2016” above for notes about the quality of information provided on clearance by individual states.)

Other issues affecting clearance operations

Funding

Inadequate funding was cited as a challenge to achieving Article 5 implementation deadlines by the following States Parties: Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Iraq, Niger, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

Although DRC can achieve its Article 5 deadline, it reported funding difficulties.

National ownership

Almost all Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with contamination have a national mine action program or institutions that are assigned to fulfil the state’s clearance obligations. In Turkey, the Turkish Mine Action Center (TURMAC) was established in 2015, but political events in 2016 resulted in institutional changes. A capacity needs assessment was conducted in 2016 to form the basis for future capacity development.[67]

Ukraine is taking steps toward the establishment of a national mine action program.[68]

In Afghanistan in October 2016, UNMAS formally handed leadership of the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA) to the Directorate of Mine Action (DMAC).[69] The UN Mine Action Center for Afghanistan (UNMACA) changed its name to “UNMAS in support of DMAC” (UNMAS/DMAC) in November 2016.[70] In DRC, UNMAS reported that the transfer of responsibility to the Congolese Mine Action Center (Centre Congolais de Lutte Antimines, CCLAM) was completed in early 2016.[71] In South Sudan, the National Mine Action Authority (NMAA) reported that the transition from UN to national ownership was suspended and that NMAA lacked the basic means to fulfil its functions.[72]

States Parties Nigeria and Oman do not have national mine action programs.

In contrast, fewer than half of states not party have functioning mine action programs.[73] There were no new mine action programs established among states not party in 2016. The following 12 states not party do not have national mine action programs: China, Cuba, Kyrgyzstan, India, Morocco, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, Syria, and Uzbekistan. Egypt’s mine clearance program is not functioning[74] and the status of Iran’s mine action center is not clear. Some of these states not party are among the most contaminated countries in the world. Yet the understanding of the extent of contamination, and the scale of land release efforts, is much lower than in States Parties. This underlines the importance of striving for universalization of the Mine Ban Treaty in order to address the threat posed by antipersonnel mines.

All the other areas (Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Western Sahara) have mine action centers.

Clearance in conflict

In 2016 and 2017, conflict affected land release operations in 11 States Parties (Afghanistan, Chad, Colombia, Iraq, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Ukraine, and Yemen) and four states not party (Libya, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Syria). Insecurity has also restricted access to some areas that are or may be antipersonnel mine-affected in DRC,[75] Ethiopia,[76] Jordan,[77] Senegal,[78] Tajikistan,[79] Turkey,[80] and Western Sahara. In Tajikistan, in 2015 and 2016, survey and clearance operations were restricted on the border with Afghanistan due to insecurity. However, improved security conditions in 2017 enabled full survey and clearance operations to resume.[81]

In South Sudan, a resurgence in violence forced mine action operations to close in the second half of 2016.[82]

In Libya and Syria, where there is limited clearance capacity, international mine action clearance operators continued to focus their efforts on capacity building and training of national actors, much of it taking place outside the country.[83] In Ukraine, the State Emergency Services (SESU), which is responsible for humanitarian demining, suffered severe losses of buildings and vehicles during the conflict. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Project Coordinator and Danish Demining Group (DDG) provided the SESU with equipment and training in 2016 to support their operational capacity.[84]

In 2016, a number of security incidents directly affected demining activities, several resulting in casualties. In Afghanistan in 2016, nine deminers were killed and 10 injured in attacks by armed groups.[85] In Chad, a number of deminers were killed and injured in mine blasts during missions in the north, east, and west of the country.[86] In Colombia in 2017, Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) staff had to leave an area due to direct threats from a dissident FARC faction.[87] In Somalia in 2016, two demining staff were killed and one injured in a shooting incident, reportedly due to a conflict between rival sub-clans that was not directly targeted at demining operations, but which nevertheless forced HALO to withdraw from the areas.[88] In South Sudan in 2016, three mine action staff were killed and three injured during shooting incidents.[89]

Cyprus does not have effective control of antipersonnel mine-contaminated areas. In Palestine, Israel will not authorize clearance by Palestinians, and most mined areas are in zones controlled by Israel or under joint control. Ukraine has noted that it does not currently have access to some mined areas. In Azerbaijan, Armenian forces occupy a significant area of the country where considerable contamination exists.[90] In Georgia, there may be mined areas in South Ossetia, however, South Ossetia is effectively subject to Russian control and is inaccessible to the Georgian authorities and international NGOs.

In Western Sahara, the expulsion of civilian staff members of the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) by Morocco resulted in the suspension of UNMAS-contracted demining activities east of the berm from 20 March to 15 September 2016.[91]

In Myanmar, the government said that concluding a National Ceasefire Agreement with non-state actors was a precondition for proceeding with survey and clearance.[92]

Finally, and on a positive note, in Colombia, the peace process between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) gave momentum to demining planning. In 2016, as the first step in the process of implementing an agreement between the government and the FARC on demining, NPA has been leading and supervising a mine clearance project as a trust-building exercise. The Colombian army has been conducting the mine clearance as such, with NPA providing verification, while the FARC has given information on contaminated areas.[93] On 1 October 2017, a ceasefire agreement between the government of Colombia and the National Liberation Army (Unión Camilista-Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) took effect.[94] In the agreement, the ELN has committed not use antipersonnel landmines that could endanger the civilian population.

[1] The Monitor acknowledges the contributions of Mine Action Review (www.mineactionreview.org), which has conducted the mine action research in 2017, including on survey and clearance, and shared all its resulting landmine and cluster munition reports with the Monitor. The Monitor is responsible for the findings presented online and in its print publications.

[2] Declaration of Fulfilment of Article 5, submitted by Algeria, 10 February 2017, p. 8, bit.ly/AlgeriaDecl2017.

[3] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form I. Four small suspected mined areas with a combined size of 1,881m2 remained submerged under water. These areas are “suspended” and Mozambique plans to address them once the water level has receded and access can be gained. See, Declaration of Completion of Implementation of Article 5, submitted by Mozambique, 16 December 2015, p. 5; and statement of Mozambique, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 8 June 2017.

[4] Response by the Permanent Mission of South Korea to the UN in New York, 9 May 2006; and K. Chang-Hoon, “Find One Million: War With Landmines,” Korea Times, 3 June 2010.

[5] The north of Algeria is said to be contaminated by an unknown number of improvised mines laid by insurgent groups. See, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, 2017, p. 22.

[6] In Cameroon, allegations of use by Boko Haram of improvised antipersonnel mines have been reported.

[7] Djibouti completed its clearance of known mined areas in 2003 and France declared it had cleared a military ammunition storage area in Djibouti in November 2008, but there are concerns that there may be mine contamination along the Eritrean border following a border conflict in June 2008. Djibouti has not made a formal declaration of full compliance with its Article 5 obligations.

[8] Antipersonnel mine casualties were reported in Kuwait in 2016.

[9] In Mali, casualties have been reported to be caused by improvised mines. It has been reported that these mines may be activated upon contact or by the weight of a person, although they have only been reported to have been activated either by vehicles or command detonated.

[10] Moldova, which had an Article 5 deadline of 1 March 2011, made a statement in June 2008 that suggested it had acknowledged its legal responsibility for clearance of any mined areas in the breakaway republic of Transnistria, where it continues to assert is jurisdiction. However, this statement was later disavowed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 2 June 2008, bit.ly/MoldovaNSA2008.

[11] Despite a statement made by Namibia at the Second Review Conference that it was in full compliance with Article 5, questions remain as to whether there are mined areas in the north of the country, for example, in the Caprivi region bordering Angola.

[12] Palau may have residual antipersonnel mine contamination.

[13] The Philippines, which has alleged use of antipersonnel mines by non-state armed groups over recent years, has not formally reported the presence of mined areas.

[14] There have been casualties from victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in Tunisia in 2015, 2016, and 2017. Due to the nature of the ongoing conflict, it is likely that these devices were recently laid.

[15] See Mine Action country profiles available on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/cp.

[16] Email from Julie Myers, UNMAS (based on information provided by Joseph Huber, UNMAS), 24 July 2017.

[17] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), bit.ly/MBTArt7reports.

[18] Email from Tom Griffiths, HALO Trust, 31 May 2017.

[19] Email from Virginie Auger, UNMAS, 29 March 2017.

[20] In its CCW Amended Protocol II and Protocol V transparency reports for 2016, Russia reported that its armed forces engineering units conducted demining and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) in 80 regions of the country. In total, more than 306,616 explosive devices were destroyed, including 20,698 IEDs. See, CCW Amended Protocol II Article 13 Report (for 2016), Form B; and Protocol V Article 10 Report (for 2016), Form A. However, it did not report how much was mined area and how many antipersonnel mines were destroyed.

[21] See the glossary at the beginning of this report and in the Casualties chapter for definitions of IEDs and improvised mines.

[22] Danish Demining Group (DDG) calculated that an estimated 67% of the countries where DDG is present also have an IED problem. See, Robert Keeley, “Improvised Explosive Devices (IED): A Humanitarian Mine Perspective,” The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction, Issue 21.1, April 2017, p. 5.

[23] For further details, see individual country profiles on mine action and casualties on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org.

[24] Ibid.

[25] According to the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), “The scale of the IED problem remains poorly defined, although evidence to data suggests that the largest numbers of devices are associated with mass-produced improvised landmines. Numbers of booby traps and command wire/radio controlled devices in urban areas should become clearer as more operations take place in liberated towns and villages, and as more data becomes available. Until such information does become available, it is hard to predict the relative levels of effort required to address different types of IED and the associated equipment, competence and cost implications.” GICHD, “An initial study into mine action and improvised explosive devices,” February 2017, p. 49.

[26] Interview with Mohammad Shafiq Yosufi, Director, Directorate of Mine Action (DMAC), in Geneva, 9 February 2017; and Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA), “Operational Work Plan 1396,” undated but 2017, p. 2.

[27] “MAPA Operational Work Plan 1396,” undated but 2017, p. 22.

[28] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2015), Form D, bit.ly/MBTArt7reports.

[29] Data received from Ahmed Al Jasim, Directorate of Mine Action (DMA), 6 April 2017.

[30] GICHD, “An initial study into mine action and improvised explosive devices,” February 2017; MAG, “Why Principles Matter. Humanitarian Mine Action and Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs),” Policy Brief, May 2017; Robert Keeley, “Improvised Explosive Devices (IED): A Humanitarian Mine Perspective,” The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction, Issue 21.1, April 2017; Chris Loughran and Sean Sutton, “MAG: Clearing Improvised Landmines in Iraq,” The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction, Issue 21.1; and Abigail Jones, “Do no harm: the challenge of protecting civilians from the IED threat in south-central Somalia,” The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction, Issue 21.1, April 2017.

[31] Declaration of Completion of Implementation Article 5, submitted by Algeria, 10 February 2017, p. 8, bit.ly/AlgeriaDecl2017.

[32] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form I. Four small suspected mined areas with a combined size of 1,881m2 remained submerged under water. These areas are “suspended” and Mozambique plans to address them once the water level has receded and access can be gained. See, Declaration of Completion of Implementation of Article 5, submitted by Mozambique, 16 December 2015, p. 5; and statement of Mozambique, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 8 June 2017.

[33] Declaration of Completion of Implementation of Article 5, APLC/MSP.12/2012/Misc.3, Geneva, 4 December 2012.

[34] Declaration of Completion of Implementation of Article 5, APLC/MSP.14/2015/Misc.2, Geneva, 16 December 2015.

[35] Letter from Efraín Baus Palacios, Director of Neighbourhood Relations and Sovereignty for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Human Mobility, and President of the National Humanitarian Demining Center of Ecuador, to Amb. Patricia O’Brian, Permanent Representative of Ireland to the UN in Geneva, and Chair of the Article 5 Committee, Note No. 14839-DRVS/CENDESMI, Quito, 26 November 2016.

[36] Final Report, Mine Ban Treaty Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties, 14 December 2016, p. 8,bit.ly/MBTMSP15Final.

[37] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, dated 15 May 2016, submitted 15 April 2016, p. 13.

[38] Final Report, Mine Ban Treaty Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties, 14 December 2016, p. 6.

[39] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), dated July 2016, submitted 2 August 2016.

[40] Final Report, Mine Ban Treaty Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties, 14 December 2016, p. 7.

[41] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, dated 31 March 2017, submitted 11 May 2017, p. 20. The areas comprised of 1,074 confirmed areas, corresponding to 104km2, and 287 suspected hazardous areas, corresponding to 141km2.

[42] “Preliminary observations,” Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, 8–9 June 2017, pt. 46.

[43] Ecuadorian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Request for renewal of extension of the deadline to complete the destruction of antipersonnel mines in mined areas in accordance with Article 5, paragraphs 3 and 6 of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Antipersonnel Mines and on their Destruction,” March 2017.

[44] Additional information to Ecuador’s Extension Request, 8 September 2017.

[45] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 28 August 2017.

[46] Statement of the ICBL on Iraq’s Extension Request, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 8 June 2017.

[47] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), dated 30 March 2017, 8 September 2017.

[48] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), executive summary, 8 September 2017.

[49] Ibid., p. 12.

[50] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 9 August 2017.

[51] “Preliminary observations,” Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, 8–9 June 2017, pt. 287.

[52] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 9 August 2017, p. 19.

[53] Final Report, Mine Ban Treaty Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties, 14 December 2016, p. 8.

[54] Statement of Ukraine, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, Geneva, 8 June 2017.

[55] Maputo Action Plan, 27 June 2014, bit.ly/MaputoActionPlan.

[56] Preliminary Observations of the Committee on Article 5 Implementation, 23 June 2015, bit.ly/MBTArt5Prelim2015.

[57] Mine Ban Treaty Second Article 5 Extension Request, 11 May 2017, p. 5.

[58] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), p. 4; and email from Mohammad Breikat, National Committee for Demining and Rehabilitation (NCDR), 10 April 2017.

[59] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2015), Form D.

[60] UNMAS, “2017 Portfolio of Mine Action Projects, Somalia,” undated.

[61] Chile, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form F2; and Analysis of Niger’s Third Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 25 October 2016.

[62] Statement of Ethiopia, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, Geneva, 8 June 2017; and Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form G.

[63] Email from Slađana Košutić, Serbian Mine Action Center (SMAC), 6 April 2017; and Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form D.

[64] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form A; and statement of Turkey, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Victim Assistance, Geneva, 8 June 2017.

[65] Declaration of Completion of Implementation of Article 5, submitted by Algeria, 10 February 2017, p. 8, bit.ly/AlgeriaDecl2017.

[66] “Preliminary observations,” Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, 8–9 June 2017, pt. 22.

[67] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form H; statement of Turkey, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Enhancement of Cooperation and Assistance, Geneva, 8 June 2017; and email from Lt.-Col. Halil Şen, TURMAC, 21 June 2017.

[68] “Mine Action Activities,” Side-event presentation by Amb. Vaidotas Verba, Head of Mission, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Project Coordinator in Ukraine, at the 19th International Meeting of Mine Action National Programme Directors and UN Advisors, Geneva, 17 February 2016.

[69] Interviews with Mohammad Shafiq Yosufi, DMAC, in Geneva, 9 February 2017; and with Yngvil Foss, Country Programme Manager, UNMAS, in Geneva, 6 February 2017.

[70] Email from Mohammad Wakil Jamshidi, Chief of Staff, UNMAS/DMAC, 16 May 2017.

[71] UNMAS, “About UNMAS Support of One UN and the GODRC,” March 2016, www.mineaction.org/print/programmes/drc.

[72] Interview with Jurkuch Barach Jurkuch, NMAA, in Geneva, 6 September 2017.

[73] Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Israel, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

[74] In January 2017, Egypt’s Minister of International Cooperation, Sahar Nasr, announced the establishment of the National Centre for Landmine Action and Sustainable Development. Minister Nasr said that the center would begin clearing 600km2 on the northern coast and would also establish infrastructure after clearance was completed. See, H. Salah, “Establishment of National Center for Mines Action and Sustainable Development completed: Nasr,” Daily News Egypt, 23 January 2017, www.dailynewsegypt.com/2017/01/23/612214/.

[75] Mine Ban Treaty Second Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 7 April 2014, p. 10; and UNMAS, “2015 Portfolio of Mine Action Projects, Democratic Republic of the Congo,” undated.

[76] “Response to Committee on Article 5 Implementation request for additional information on its Article 5 deadline Extension Request,” 26 September 2015; and Analysis of Ethiopia’s Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 19 November 2015, p. 3.

[77] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), p. 4; and email from Mohammad Breikat, NCDR, 10 April 2017.

[78] Email from Ibrahima Seck, Senegalese National Mine Action Center (Centre National d’Action Antimines, CNAMS), 22 August 2016.

[79] Emails from Muhabbat Ibrohimzoda, Tajikistan National Mine Action Center (TNMAC), 19 August 2016, and 22 May 2017; and from Aubrey Sutherland, NPA, 14 March 2017; and statement of Tajikistan, Mine Ban Treaty 15th Meeting of States Parties, Santiago, 30 November 2016.

[80] Email from Lt.-Col. Halil Şen, TURMAC, 21 June 2017.

[81] Emails from Muhabbat Ibrohimzoda, TNMAC, 19 August 2016, and 22 May 2017; and from Aubrey Sutherland, NPA, 14 March 2017; and statement of Tajikistan, Mine Ban Treaty 15th Meeting of States Parties, Santiago, 30 November 2016.

[82] Email from Robert Thompson, UNMAS, 19 April 2017; and UNMAS, “2017 Portfolio of Mine Action Projects: South Sudan,” undated.

[83] Email from Lyuba Guerassimova, Programme Officer, UNMAS Libya, 28 February 2017; Implementing Partners Coordination Meeting, Tunis, 19 January 2017; emails from Lutz Kosewsky, DDG, 22 February 2017; and from Catherine Smith, Handicap International (HI), 22 February 2017; and interview with Luke Irving, Specialist Training and EOD Manager, and Nour Saleh, Project Officer, Mayday Rescue, and Majid Khalaf, EOD Liaison Officer, Syria Civil Defense (SCD), in Geneva, 5 September 2017.

[84] Emails from Rowan Fernandes, DDG Ukraine, 20 May and 17 June 2016; and from Anton Shevchenko, OSCE, 14 June 2016.

[85] Email from Feda Mohammad Oriakhil, Project Officer, DMAC, 30 September 2017.

[86] “Tchad: grève des démineurs restés 10 mois sans salaire” (“Chad: deminers strike after 10 months without pay”), Agence de Presse Africaine, 10 May 2017, http://mobile.apanews.net/index.php/fr/news/tchad-greve-des-demineurs-restes-10-mois-sans-salaire; and email from Julien Kempeneers, HI, 26 September 2017.

[87] Email from Vanessa Finson, NPA, 12 September 2017.

[88] Email from Tom Griffiths, HALO Trust, 31 May 2017.

[89] Email from William Maina, DDG, 2 May 2017; and Danish Refugee Council, “Two national employees have lost their lives in South Sudan,” 12 April 2016, http://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/two-national-employees-have-lost-their-lives-south-sudan; and emails from Bill Marsden, MAG, 11 May 2017, and 21 October 2016.

[90] Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA), “Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action 2017,” undated, p. 5.

[91] “Report of the Secretary-General on the situation concerning Western Sahara,” UN doc. S/2017/307, 10 April 2017, p. 8; R. Gladstone, “Morocco Orders U.N. to Cut Staff in Disputed Western Sahara Territory,” The New York Times, 17 March 2016, bit.ly/NYTMoroccoUNWesternS2016; and What’s in Blue: Insights on the work of the UN Security Council, “Western Sahara: Arria-formula Meeting, Consultations, and MINURSO Adoption,” 26 April 2016, bit.ly/WhatsInBlue26Apr2016.

[92] Roger Fasth and Pascal Simon, “Mine Action in Myanmar,” Journal of Mine Action, Issue 19.2, July 2015.

[93] Email from Fredrik Holmegaard, Project Manager, Humanitarian Disarmament – Colombia, NPA, 13 June 2016.

[94] “Colombia Cease-Fire Agreement Takes Effect Sunday,” Voice of America, 30 September 2017, www.voanews.com/a/colombia-cease-fire-takes-effect-october-1/4050834.html.