Landmine Monitor 2022

The Impact

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Contamination | Casualties | Clearance | Risk Education | Victim Assistance

This chapter highlights developments and challenges in assessing and addressing the impact of antipersonnel mines. It documents progress toward the half-way mark of the Mine Ban Treaty’s Oslo Action Plan, which was adopted in November 2019. The plan is consistent with the fulfillment of the objectives of the treaty, whereby States Parties declare that they are:

“Determined to put an end to the suffering and casualties caused by anti-personnel mines, that kill or maim hundreds of people every week, mostly innocent and defenseless civilians and especially children, obstruct economic development and reconstruction, inhibit the repatriation of refugees and internally displaced persons, and have other severe consequences for years after emplacement.”[1]

The first part of this overview covers contamination and casualties, while the second part focuses on addressing the impact through clearance, risk education, and victim assistance. These make up three of the five core components or “pillars” of mine action.

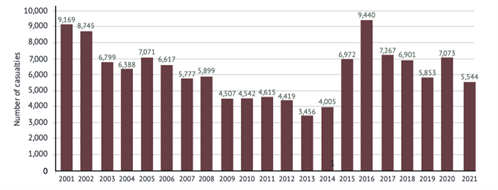

According to available data, at least 5,544 people were killed or injured by landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) globally in 2021. This represents a significant decrease from the 7,073 casualties recorded in 2020, but remains high compared to 2013, the year when the fewest reported casualties occurred.

In 2021, casualties were recorded in 47 states, of which 36 are States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, and also in three other areas. States Parties accounted for almost two-thirds of all annual casualties. The majority of casualties during 2021 occurred in conflict-affected countries which have contamination by mines of an improvised nature.

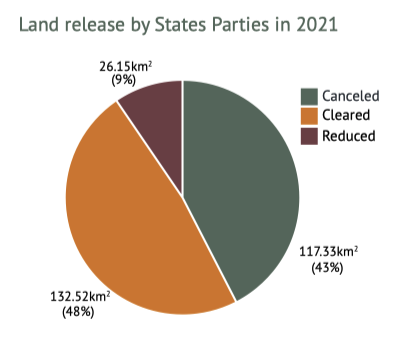

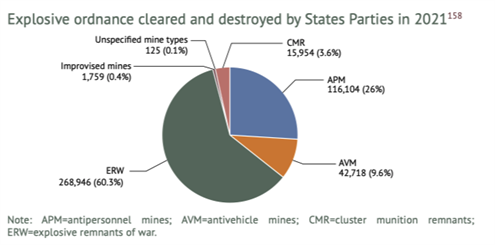

Positive progress was observed in 2021 as just over 276km² of land known or suspected to be contaminated by antipersonnel landmines was released by States Parties and returned to local communities. Of this, 132.52km² was cleared, 26.15km² was reduced via technical survey, and 117.33km² was canceled through non-technical survey. More than 117,800 antipersonnel mines were cleared and destroyed. While the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic lingered in some States Parties, the majority were able to resume near-to-normal operations.

Despite this progress, the outlook for meeting the aspirational goal “to clear all mined areas as soon as possible, to the fullest extent by 2025,” looks less than optimistic.[2] No State Party reported completion of clearance during 2021. Eight States Parties with Article 5 clearance obligations undertook no clearance in 2021, six of which have conducted no clearance for two years. While some States Parties are making every effort to meet their deadlines, in other States Parties progress has been negligible. Twenty-three States Parties have deadlines to meet their Article 5 obligations either before or during 2025, but very few appear on track to meet these deadlines.

Ongoing armed conflict in some States Parties and the increasing use of improvised landmines is compounding the complexity and slowing the pace of survey and clearance. Seven States Parties with improvised mine contamination need to clarify their status with regard to their clearance obligations. Three States Parties with residual contamination have not reported on progress to clear this contamination, in line with their treaty obligations.

Mine/ERW risk education remained a crucial intervention as people continued to live and work in contaminated areas and in states suffering ongoing conflict, including Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and Yemen, and in 2022, Ukraine. The Oslo Action Plan outlines commitments to improve the prioritization and provision of context-specific risk education, to build national capacity, and to integrate risk education with humanitarian, protection, and development interventions.

Risk education was conducted in at least 30 States Parties during 2021, with many examples of improved prioritization and targeting of at-risk groups. Risk education was incorporated into the United Nations (UN) Protection Cluster and humanitarian response plans for some States Parties, while efforts continued to build capacity of local actors and networks to deliver risk education. The use of mass and digital media to expand coverage of risk education continued, and in some cases helped reach people in inaccessible and conflict-affected areas.

Victim assistance is an enduring obligation that requires sustained efforts, including by States Parties that remain mine-affected as well as those that have been declared mine-free. At least 34 States Parties have responsibility for significant numbers of mine victims.

The Oslo Action Plan includes commitments to enhance the core victim assistance components of emergency medical response, ongoing healthcare, rehabilitation, psychosocial support, and socio-economic inclusion. It also includes a commitment on protection of landmine victims in situations of armed conflict and humanitarian emergencies. New developments in enhancing victim assistance were reported as activities began to recover after the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet in several states, progress was hampered by a lack of funding and resources, inadequate or barely functioning healthcare and social systems, and ongoing armed conflict.

Assessing The Impact

Antipersonnel mine contamination

Antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties

- States Parties with Article 5 obligations

As of October 2022, a total of 67 states and other areas were either known or suspected to be contaminated with antipersonnel mines. Of these, 33 States Parties had declared an identified threat of antipersonnel mine contamination on territory under their jurisdiction or control, and have obligations under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty. This includes Argentina, which has yet to acknowledge the completion of mine clearance by the United Kingdom (UK) on the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. Eritrea has been in a state of non-compliance since its Article 5 clearance deadline expired on 31 December 2020.

Seven States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty—Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, the Philippines, Tunisia, and Venezuela—are known or believed to have contamination by improvised mines, but have not provided information or recognized having clearance obligations under Article 5.

Twenty-two states not party to the treaty and five other areas have, or are believed to have, land contaminated by antipersonnel mines on their territory.

States Parties that have declared Article 5 obligations as of October 2022

|

Afghanistan |

Eritrea |

Serbia |

|

Angola |

Ethiopia |

Somalia |

|

Argentina* |

Guinea-Bissau |

South Sudan |

|

BiH |

Iraq |

Sri Lanka |

|

Cambodia |

Mauritania |

Sudan |

|

Chad |

Niger |

Tajikistan |

|

Colombia |

Nigeria |

Thailand |

|

Croatia |

Oman |

Türkiye |

|

Cyprus** |

Palestine |

Ukraine |

|

DRC |

Peru |

Yemen |

|

Ecuador |

Senegal |

Zimbabwe |

*Argentina was mine-affected by virtue of its assertion of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. The UK also claims sovereignty and exercises control over the territory and completed clearance in 2020. Argentina has not yet acknowledged completion.

**Cyprus has stated that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under its control.

- States Parties that have completed clearance

Under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, States Parties are required to clear all antipersonnel mines as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the treaty.

No States Parties reported completion of clearance of antipersonnel mines in 2021. Since the treaty came into force in 1999, a total of 30 States Parties have reported clearance of all antipersonnel mines from their territory.[3] State Party El Salvador completed mine clearance in 1994, before the treaty came into force.

States Parties that have declared fulfillment of clearance obligations since 1999

|

1999 |

Bulgaria |

2010 |

Nicaragua* |

|

2003 |

Costa Rica |

2012 |

Republic of Congo, Denmark, Gambia, Uganda |

|

2004 |

Djibouti, Honduras, Suriname |

2013 |

Bhutan, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Venezuela** |

|

2005 |

Guatemala |

2014 |

Burundi |

|

2006 |

North Macedonia |

2017 |

Algeria,* Mozambique* |

|

2007 |

Eswatini |

2018 |

Jordan |

|

2008 |

France, Malawi |

2020 |

Chile, UK |

|

2009 |

Albania, Rwanda, Tunisia,** Zambia |

|

|

*Algeria, Mozambique, and Nicaragua have reported, or are suspected to have, residual contamination.

**Tunisia and Venezuela are suspected to have improvised mine contamination. Tunisia also has residual contamination.

Several States Parties that had declared themselves free of antipersonnel mines later discovered previously unknown mine contamination, or were required to verify that areas had been cleared to humanitarian standards.[4] Burundi, Germany, Greece, Hungary, and Jordan each declared the fulfillment of their obligations under Article 5 several years after their initial declarations.

Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, and Nigeria all reported the discovery of further contamination and submitted extension requests in 2020–2021.

- Extent of contamination in States Parties

Nine States Parties—Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Croatia, Ethiopia, Iraq, Türkiye, Ukraine, and Yemen—have all reported massive antipersonnel landmine contamination (more than 100km²). The extent of contamination in both Ethiopia and Ukraine cannot be reliably verified until survey has been conducted. Both countries have ongoing conflict which is adding to the overall contamination by explosive ordnance.[5]

Large contamination by antipersonnel landmines (20–99km²) is reported in five States Parties: Angola, Chad, Eritrea, Thailand, and Zimbabwe.

Medium contamination (5–19km²) is reported in six States Parties: Mauritania, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, and Tajikistan.

Eleven States Parties have reported less than 5km² of contamination: Colombia, Cyprus, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, Oman, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, and Serbia.

The extent of contamination in Nigeria is not known.

Estimated antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties

|

Massive (more than 100km²) |

Large (20–99km²) |

Medium (5–19km²) |

Small (less than 5km²) |

Unknown

|

|

Afghanistan BiH Cambodia Croatia Ethiopia* Iraq Türkiye Ukraine* Yemen |

Angola Chad Eritrea Thailand Zimbabwe |

Mauritania Somalia South Sudan Sri Lanka Sudan Tajikistan |

Colombia Cyprus** DRC Ecuador Guinea-Bissau Niger Oman Palestine Peru Senegal Serbia |

Nigeria

|

*Ethiopia and Ukraine have reported massive contamination; this cannot be reliably verified until survey has been conducted.

**Cyprus has stated that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under its control.

Americas

As of the end of 2021, Colombia reported 2.96km² of antipersonnel landmine contamination, across 66 municipalities and 12 departments. The contamination, mostly by improvised mines, covered 219 confirmed hazardous areas (CHAs) totaling 1.63km² and 188 suspected hazardous areas (SHAs) totaling 1.33km². Colombia reported that 80 new SHAs totaling 0.74km² and 93 CHAs totaling 0.61km² were identified in 2021.[6] Eighteen municipalities were declared mine-free in 2021. A further 185 municipalities were known to be affected by antipersonnel mines, though the extent of their contamination remained unknown. This included 131 municipalities that were not accessible for security reasons.[7]

Ecuador and Peru each have a very small amount of remaining landmine contamination. As of the end of 2021, Ecuador had 0.04km² of contaminated land (0.03km² CHA and 0.01km² SHA), containing around 2,941 mines.[8] Peru’s contamination totaled 0.36km², across 102 CHAs.[9]

East and South Asia and the Pacific

Afghanistan reported antipersonnel mine contamination totaling 188.26km² (144.6km² CHA and 43.66km² SHA) as of the end of July 2022. This included 43.9km² of improvised mine contamination.[10] Prior to the Taliban taking control of Afghanistan in August 2021, new mine contamination resulting from fighting between the government and non-state armed groups (NSAGs) added to the extent of contamination in the country.[11]

As of the end of 2021, Cambodia reported landmine contamination totaling 715.9km².[12] This land is not differentiated as CHA or SHA in the national database. The northwest region bordering Thailand is heavily affected, while other parts of the country in the east and northeast are primarily affected by ERW. Much of the remaining contamination in Cambodia and Thailand is along their shared border, where access has been problematic due to a lack of border demarcation.[13]

Contamination in Sri Lanka remains in the Northern, Eastern, and North Central provinces. In total, 11.89km² of contaminated land covered 336 CHAs (10.93km²) and 24 SHAs (0.96km²), as of December 2021.[14] The most significant mine contamination (11.52km²) is found in five districts of Northern province, which were the site of intense fighting during the civil war.[15]

Thailand had some 40km² of contaminated land across 18 districts in seven provinces. Of this, 21.78km² was classified as CHA and 4.2km² as SHA. A total of 14.04km² across 31 areas was on land yet to be demarcated on the border with Cambodia.[16] Thailand has also seen use of improvised mines by insurgents in the south, but the extent of contamination by these mines is unknown and has not been recorded by the Thailand Mine Action Center (TMAC).

Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia

BiH reported extensive contamination totaling 922.37km² as of the end of 2021.[17] BiH did not provide a breakdown in terms of CHA and SHA. However, at the end of 2020, BiH had reported contamination of 956.36km², with 95km² classified as CHA and 861.36km2 as SHA.[18] This marked a significant increase in the amount of land classified as CHA compared to May 2020, when just 20.75km² was classified as CHA.[19]

As of the end of 2021, Croatia reported mine contamination totaling 204.4km² (136.8km² CHA and 67.6km² SHA) across seven of its 21 counties.[20] In addition, 29.5km² of contaminated land is under military control. According to minefield records, the land outside of military control is thought to contain around 13,856 antipersonnel mines and 921 antivehicle mines.[21] Most of the remaining contaminated land in Croatia is reported to be in forested areas, where clearance projects are aligned with conservation and nature protection regulations.[22]

Cyprus is believed to have 1.24km² of antipersonnel and antivehicle landmine contamination (0.43km² CHA and 0.81km² SHA) across 29 areas. Yet the contamination is reported to be only in Turkish-controlled Northern Cyprus and in the buffer zone, and not in territory under the effective control of Cyprus.[23]

Serbia reported 0.56km² of mine contamination across three areas in Bujanovac municipality, all classified as SHA.[24] New areas of suspected contamination in Bujanovac were identified after explosions caused by forest fires in 2019 and 2021, but have not yet been surveyed.[25]

Tajikistan reported 11.82km² of antipersonnel mine contamination (7.34km² CHA and 4.48km² SHA) as of the end of 2021. The majority of the SHA is located on the Tajikistan-Uzbekistan border, covering 3.25km² across 54 areas.[26]

Türkiye reported contamination of 140.59km² across 3,804 areas. Most contaminated areas are found along its borders with Armenia, Iran, Iraq, and Syria; whilst 919 areas are not in border regions.[27] Türkiye began conducting non-technical survey in June 2021, and aims to survey all contaminated areas by 2023 to provide a more accurate picture of contamination.[28] In addition to mines laid by Turkish security forces, the contamination also includes improvised mines and other explosive devices laid by NSAGs.[29]

In 2018, Ukraine provided an estimate of 7,000km² of undifferentiated contamination, including antipersonnel landmines, in government-controlled areas within the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and an estimated 14,000km² in areas not controlled by the government.[30] Ukraine had planned to conduct survey to provide a more accurate baseline of contamination in accessible areas,[31] but the outbreak of conflict following Russia’s invasion in February 2022 stalled progress and has significantly added to overall contamination, including antipersonnel mines.[32] In July 2022, the National Mine Action Authority (NMAA) of Ukraine reported that 160,000km² of Ukrainian territory had been exposed to conflict and would require survey, with around 120,000km² of that territory under the control of Russian forces at the time.[33]

Middle East and North Africa

Iraq is dealing with contamination by improvised landmines in areas liberated from the Islamic State, in addition to legacy mine contamination from the 1980–1988 war with Iran, the 1991 Gulf War, and the 2003 invasion by a United States (US)-led coalition. As of the end of 2021, Iraq reported 1,208.85km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, and an additional 527.15km² of contamination from improvised explosive devices (IEDs), including improvised landmines. Most of the contamination is located in territory under the government of Federal Iraq.[34]

Oman reported that all of its hazardous areas had been cleared before it joined the Mine Ban Treaty, but were in the process of being “re-inspected” to deal with residual risk.[35] As of the end of 2020, Oman reported that remaining suspected contamination totaled 0.68km², and that it planned to re-clear seven areas totaling 0.51km² between February 2021 and April 2024.[36] As of October 2021, Oman had not submitted an Article 7 report to update on progress.

In 2021, Palestine reported 0.18km² of landmine contamination, of which 0.08km² was antipersonnel mines and 0.1km² was antivehicle mines.[37] Sixteen confirmed minefields are located within the West Bank and an additional 65 minefields are located on the border with Jordan. No clearance was conducted in 2021 due to a lack of financial support.[38]

Yemen does not possess a clear understanding of its level of mine contamination, as ongoing armed conflict adds to the extent and complexity of contamination, which includes improvised mines.[39] The Sarawat mountains and surrounding coastal areas are particularly impacted.[40] The scale and impact of conflict has prevented implementation of effective nationwide survey.[41] The most recent contamination estimate was 323km², as of March 2017.[42] In June 2021, non-technical survey began, with the aim of calculating a national baseline of contamination.[43]

Sub-Saharan Africa

As of the end of 2021, Angola reported total antipersonnel mine contamination of 71.49km², across 16 provinces and 1,097 areas. The provinces of Cuando Cubango and Moxico were the most heavily contaminated, with 17.3km² and 13.13km² respectively.[44] Angola did not report how much of its remaining contaminated land was classified as CHA.[45]

As of the end of 2021, Chad had identified a total of 126 hazardous areas, with 73 classified as CHA, located in the provinces of Borkou, Ennedi, and Tibesti.[46] Contamination was reported to be mixed, and covered a total area of 78.33km² (56.59km² CHA and21.74km² SHA).[47] Over half of Chad’s mine contamination (43.24km²) was located in Tibesti province.[48] Lake province was reported to be contaminated with improvised mines.[49]

The remaining mine contamination in the DRC is small. In June 2021, contamination totaled 0.12km² (0.09km² CHA and 0.03km² SHA) across 33 areas, affecting nine of the 25 provinces in the DRC.[50] In March 2022, the DRC reported new contamination after a national survey and clean-up of the national database, resulting in total contamination of 0.4km² across 37 CHAs.[51] Areas on the borders with Uganda and South Sudan had not been surveyed due to insecurity.[52] Improvised mine contamination has been identified in Ituri and North-Kivu provinces.[53] These mines were reportedly planted in agricultural land to prevent farmers working in their fields.[54]

Eritrea has not reported on the extent of its contamination since 2014, when it was estimated at 33.5km².[55] Eritrea remains in violation of the Mine Ban Treaty by virtue of its failure to meet its clearance deadline and submit an extension request.

In June 2022, Ethiopia reported remaining contamination of 726.07km², across 152 areas in six provinces; the same contamination figure reported in April 2020.[56] Of this, 29 areas were classified as CHA (3.52km²), while 123 areas were SHA (722.55km²).[57] Most SHAs are located in the Somali region. It is believed that the baseline figure is an overestimate, and that only 2% of these areas contain landmines.[58] The conflict in northern Ethiopia since November 2020 has left significant contamination with explosive ordnance, though the extent and type of contamination there is yet to be fully established.[59] Separate armed conflicts are ongoing in other regions of Ethiopia, particularly in Oromia and Benishangul Gumuz.[60]

Guinea-Bissau had declared fulfillment of its clearance obligations in December 2012, but in June 2021 reported further mine/ERW contamination.[61] As of the end of 2021, Guinea-Bissau reported 1.09km² of CHA in North province (0.49km² of antipersonnel mine and 0.6km² of antivehicle mine contamination). In addition, another 43 areas across North, East, and South provinces were suspected to contain both mines and ERW. Guinea-Bissau planned to undertake a national survey to determine the extent of remaining contamination.[62]

Mauritania declared clearance of all known contamination in 2018, but later identified new mined areas.[63] As of the end of 2021, Mauritania reported 14.93km² of mine contamination, with 14.39km² affected by antipersonnel mines and 0.54km² by antivehicle mines.[64]

In 2021, Niger reported 0.18km² of CHA, adjacent to a military post in Madama, in the Agadez region.[65] This figure has not changed since its Article 5 extension request was granted in 2020. The estimate of remaining contamination is unclear in part due to contamination and casualties from mines and improvised devices in western Niger.[66] In 2022, Niger reported that it could not guarantee clearance would be completed by its 2024 deadline due to several challenges, including weather conditions, lack of funding, and the threat posed by NSAGs.[67] Niger has provided no further information on the extent of contamination by improvised mines.

In 2019, Nigeria reported improvised mine contamination.[68] Nigeria is impacted by improvised mines, IEDs, and ERW, mainly in the states of Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe in the northeast.[69] Nigeria was granted a second extension to its clearance deadline in 2021. It reported that due to insecurity, the extent of contamination had not yet been determined.[70]

Senegal reported that following non-technical survey in 2020, a total of 37 hazardous areas had been identified, covering 0.49km².[71] As of the end of 2021, Senegal reported nine other areas with possible contamination and 118 localities still to be surveyed.[72]

In its Article 5 deadline extension request submitted in September 2021, Somalia reported 6.1km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, out of a total of 161.8km² of mixed contamination which included antivehicle mines.[73] Somalia also reported increased use of improvised mines.[74] Since 2017, the Somali Explosives Management Authority (SEMA) has been synchronizing and verifying data in its national database, which may lead to adjustments to overall contamination figures.[75] This process was ongoing in 2021. As of October 2022, Somalia had not provided an update on the extent of contamination, though some clearance was conducted in 2021.

South Sudan reported 7.4km² of contamination as of the end of 2021, with 2.99km² CHA and 4.41km² SHA across 25 counties in eight states.[76] The largest SHA, in Jonglei state, totaled 1.98km², but it is thought that its size will be reduced through survey.

As of the end of 2021, Sudan reported 13.28km2 of antipersonnel landmine contamination, with 3.32km² CHA and 9.96km² SHA across the states of Blue Nile, South Kordofan, and West Kordofan.[77] In 2021, 1.08km² of contaminated land was newly identified in Sudan.[78]

As of the end of 2021, contamination in Zimbabwe totaled 23.51km2. This contamination is all classified as CHA and is mostly located along the border with Mozambique in four provinces, with one inland minefield in Matabeleland North province.[79]

- Suspected improvised antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties

Improvised devices designed to detonate—or which due to their design, can be detonated—by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person, are prohibited under the Mine Ban Treaty.[80] Available information indicates that the fusing of most improvised landmines allows them to be activated by a person, though there may be exceptions.

Improvised mines are noted as a concern in the Oslo Action Plan, recognizing that “new use of antipersonnel mines in recent conflicts, including those of an improvised nature, has added to the remaining challenge of some States Parties in fulfilling their commitments under Article 5.”

Action 21 of the Oslo Action Plan lays out the commitments of States Parties affected by improvised mines, whereby all provisions and obligations of the Mine Ban Treaty apply to such contamination. This includes the obligation to clear these devices under Article 5, and to provide regular information on the extent of contamination, disaggregated by type of mines, in annual transparency reporting under Article 7.

At least 20 States Parties are believed or known to have improvised mine contamination.[81] Seven of these States Parties have not declared clearance obligations under Article 5 and have not submitted regular Article 7 transparency reports: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the CAR, Mali, the Philippines, Tunisia, and Venezuela. These States Parties must clarify their status with regards to their Article 5 obligations and may need to request new clearance deadlines.

In Burkina Faso, IED use by NSAGs has been recorded since 2016. Pressure-plate improvised antivehicle mines have been increasingly used since 2018, due to the introduction of measures which block signals to command-detonated IEDs. Casualties of improvised mines have been recorded in 2020 and 2021, although most incidents involved vehicles, including cars, carts, and bicycles. However, a few incidents appear to have involved people walking. All 35 casualties in 2021 were civilians.

Cameroon originally declared that there were no mined areas under its jurisdiction or control, and its Article 5 clearance deadline expired in 2013. However, since 2014, improvised mines have caused casualties, particularly in the north on the border with Nigeria, as Boko Haram’s activities have escalated.[82] The extent of contamination is unknown but thought to be small. Most casualties in past years were traveling by vehicle. In 2021, of the 14 improvised mine casualties recorded in Cameroon, all civilians, only one incident occurred when the person stepped on the mine.[83]

In the CAR, the conflict between government forces and rebel groups has escalated since 2020, with an increase in the use of mines, including improvised mines, and other IEDs, particularly in the west.[84] In April 2021, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) reported that antipersonnel mines had been found for the first time in the country.[85] The CAR has not submitted an Article 7 transparency report since 2004.

Mali has confirmed antivehicle landmine contamination, and since 2017 has seen a significant rise in incidents caused by IEDs, including improvised mines, in the center of the country.[86] All casualties to date were traveling by vehicle. The Monitor recorded 195 improvised mine casualties in Mali in 2021. The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) has reported that improvised mines in Mali are victim-activated by pressure tray or wire trap.[87]

The Philippines has reported that it has no remaining mined areas, although risk education is still conducted due to ERW contamination.[88] Yet casualties from improvised mines continue to be reported in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in the south. In November 2019, at the Eighteenth Meeting of States Parties, the Philippines reported that the New People’s Army had continued to use weapons causing injuries, and that their use of “improvised explosive devices with anti-personnel characteristics is well-documented.”[89] The use of improvised mines by other NSAGs has also been documented.[90] In 2021, the Monitor recorded two improvised mine casualties in the Philippines.

Tunisia declared completion of its clearance obligations in 2009.[91] However, there is known to be residual contamination and there have been reports of both civilian and military casualties from mines—including improvised mines—in the last five years.[92] In 2021, of the 10 casualties recorded in Tunisia, half were civilians.[93]

Venezuela reported meeting its Article 5 obligations in 2013.[94] Yet in August 2018, local media reports said that Venezuelan military personnel suffered an antipersonnel landmine incident in Catatumbo municipality, in Zulia state, along the border with Colombia.[95] Colombian NSAGs were believed to be using improvised mines to protect strategic positions in the area.[96] After a confrontation in March 2021 between Venezuelan troops and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) in Victoria, Apure state, a Venezuelan non-governmental organization (NGO) stated that mines “similar to those used in Colombia” were found in the area.[97] Contamination was later confirmed by a member of parliament and the Ministry of Defense.[98] Venezuela reported that the military would clear the area, but has also requested UN support to clear mines from the border.[99]

- States Parties with residual contamination

Five States Parties were known or suspected to have residual contamination in 2021.

Algeria declared fulfillment of its Article 5 obligations in December 2016, but continues to find and destroy antipersonnel mines along its southwestern borders. In 2021, Algeria reported that 1,725 antipersonnel mines were found and destroyed; a decrease from 8,813 in 2020.[100] Algeria has stated that mines are immediately reported and destroyed, in accordance with the treaty.[101]

Mine and ERW casualties have been reported in Kuwait since 1990, including in 2021. In 2018, there were reports of torrential rain having unearthed landmines, presumed to be remnants of the 1991 Gulf War.[102] Landmines are believed to be present mainly on Kuwait’s borders with Iraq and Saudi Arabia, in areas used by shepherds for grazing animals. Kuwait has not made a formal declaration of contamination in line with its Article 5 obligations.

Mozambique was declared mine-free in 2015, but reported that it is dealing with some residual and isolated mine contamination throughout the country.[103] Four small suspected mined areas totaling 1,881m² were reported in 2018 to be located underwater in Inhambane province. Mozambique stated that it would address these areas once the water level had receded, allowing access.[104] Mozambique has provided no further updates on these areas since 2019.

Nicaragua declared completion of clearance under Article 5 in April 2010, but has since found residual contamination. Fifteen reports of explosive ordnance from the public in 2021 resulted in the clearance of 4,190m² and the destruction of one antipersonnel landmine and 544 ERW. Nicaragua confirmed that these contingency operations would continue through 2022.[105]

Tunisia reported the clearance of all minefields laid in 1976 and 1980 along its borders with Algeria and Libya. Yet since declaring completion of clearance in 2009, Tunisia has reported a residual mine/ERW threat remaining from World War II in El Hamma, Mareth, and Matmata in the south; Faiedh and Kasserine in the center; Cap-Bon in the north; and in the northwest.[106] Tunisia has not provided updates on efforts to clear this residual contamination.

Antipersonnel mine contamination in states not party and other areas

Twenty-two states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, and five other areas have, or are believed to have, land contaminated by antipersonnel landmines on their territory.

States not party and other areas with antipersonnel mine contamination

|

Abkhazia |

Israel |

North Korea |

|

Armenia |

Kosovo |

Pakistan |

|

Azerbaijan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Russia |

|

China |

Lao PDR |

Somaliland |

|

Cuba |

Lebanon |

South Korea |

|

Egypt |

Libya |

Syria |

|

Georgia |

Morocco |

Uzbekistan |

|

India |

Myanmar |

Vietnam |

|

Iran |

Nagorno-Karabakh |

Western Sahara |

Note: other areas are indicated in italics.

State not party Nepal and other area Taiwan have completed clearance of known mined areas since the Mine Ban Treaty came into existence in 1999.

- States not party

The extent of contamination is unknown in most states not party.

Landmines are known or suspected to be located along the borders of several states not party, including Armenia, China, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, North Korea, South Korea, and Uzbekistan.

Ongoing conflict, insecurity, and the impact of improvised mines affect states not party Egypt, India, Libya, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Syria.

The extent of contamination in Azerbaijan is not known. After the conflict with Armenia ended in September 2020, Azerbaijan gained control of areas along the former line of contact between Armenia and Azerbaijan—an area heavily contaminated with mines/ERW.[107] The Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) was cooperating with the Ministry of Emergency Situations, the Border Services Command, and the Turkish military to clear these areas.[108]

In Georgia, five landmine contaminated areas remain in Tbilisi-administered territory, totaling 2.29km² (0.12km² contaminated with antipersonnel mines and 2.17km² with antipersonnel and antivehicle mines). Yet the full extent of contamination in these areas was unknown due to lack of survey.[109]

Israel reported some 90km² of contamination in 2017 (41.58km² CHA and 48.51km² SHA), including areas in the West Bank.[110] This did not include mined areas “deemed essential to Israel’s security.” No updates on contamination have been provided since 2017—although Israel reported progress in re-surveying mine-affected areas and clearance of 0.18km² in 2020, and 0.56km² in 2021.[111] A total of 140 mines/ERW were reported cleared in 2021, with 2.7km² of land released in the Negev desert, in the border area with Egypt.[112]

As of the end of 2021, Lebanon reported 17.87km² of CHA, including 0.37km² contaminated by improvised mines.[113] In 2021, Lebanon reported 0.03km² of newly discovered antipersonnel landmine contamination and 0.02km² of newly discovered improvised mine contamination.[114]

- Other areas

Five other areas, unable to accede to the Mine Ban Treaty due to their political status, are known to be contaminated.

As of the end of 2021, Kosovo’s mine-affected areas totaled 0.76km², with an additional 0.42km² of mixed contamination.[115] Abkhazia reported 0.01km² of antipersonnel mine contamination and 0.04km² of mixed contamination.[116]

Before the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in September 2020, Nagorno-Karabakh was reported to have 6.75km² of contamination. This included 5.62km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, 0.23km² of antivehicle mine contamination, and 0.9km² of mixed contamination.[117] After the conflict and changes in territorial control, the extent of contamination is not known. The only mine action operator in Nagorno-Karabakh, the HALO Trust, reported that its operational area had reduced by 60% following the conflict and that the presence of Russian peacekeepers had resulted in access constraints. The clearance of cluster munition remnants in urban settings was prioritized in 2021 by the HALO Trust over landmine clearance in rural areas.[118]

Contamination in Somaliland totaled 5.43km²; this included 0.64km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, 1.81km² of antivehicle mine contamination, 0.04km² of ERW contamination, and 2.94km² of mixed contamination.[119] Most of the remaining contaminated areas in Somaliland are barrier minefields or perimeter minefields around military bases.[120]

Western Sahara has minefields east of the Berm,[121] covering an area of 211.72km² (86.06km² CHA and 125.66km² SHA).[122] According to UNMAS, these minefields are contaminated with antivehicle mines, although small numbers of antipersonnel mines have also been found.[123]

Landmines of all types, as well as cluster munition remnants and ERW,[124] remain a significant threat and continue to cause indiscriminate harm globally.

At least 5,544 people were killed or injured by mines/ERW in 2021. Of that total, at least 2,182 were killed while 3,355 were injured. In the case of seven casualties, the survival outcome was unknown.[125] Mine/ERW casualties were recorded in 47 countries and three other areas in 2021.

States and areas with mine/ERW casualties in 2021

|

Americas |

East and South Asia and the Pacific |

Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia |

Middle East and North Africa |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

|

Colombia Venezuela |

Afghanistan Bangladesh Cambodia India Lao PDR Myanmar Pakistan Philippines Sri Lanka Thailand |

Armenia Azerbaijan Croatia BiH Nagorno-Karabakh Tajikistan Türkiye Ukraine |

Algeria Egypt Iran Iraq Kuwait Lebanon Libya Palestine Syria Tunisia Yemen

|

Angola Burkina Faso Cameroon CAR Chad DRC Guinea-Bissau Mali Mauritania Niger Nigeria Senegal Somalia Somaliland South Sudan Sudan Uganda Western Sahara Zimbabwe |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold. Other areas are indicated in italics.

Annual casualties rose sharply in 2015–2016 due to increased conflict and contamination. While the total number of casualties decreased from 2017 to 2019, it increased again in 2020, when 7,073 people were killed or injured by mines/ERW. Annual casualties in 2021 were close to the level recorded in 2019.[126]

In the period 2001–2021, data collected by the Monitor shows that 2013 was the year with the fewest mine/ERW casualties on record (3,456). The notable rise in annual casualties since then is primarily due to intensive armed conflicts involving the use of improvised mines.

Annual mine/ERW casualties (2001–2021)[127]

Syria had the most recorded casualties of any country or area in 2021; as was the case in 2020. For the previous two decades, Afghanistan and Colombia had alternated in recording the most annual casualties. Mine/ERW casualties in Colombia spiked in 2005–2007, while Afghanistan recorded the most casualties in 2008–2019, except for 2016, which witnessed a peak in Yemen.

Since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, the number of casualties in Syria has risen massively. Beginning in 2014, Syria recorded the second highest number of casualties after Afghanistan, which accounted for over a quarter of global mine/ERW casualties in the period 2011–2021.

In the past decade, the majority of all casualties (82%) were recorded in just 12 countries which have recorded more than 1,000 casualties over the period. All but one state with more than 1,000 casualties since 2011 have experienced mine/ERW contamination due to recent conflict and have reported casualties resulting from the use of improvised mine types. Cambodia represents a notable exception, where casualties from legacy contamination decreased from 211 in 2011 to 44 in 2021.

States with more than 1,000 casualties recorded in 2011–2021

|

State |

Number of casualties |

% of total casualties |

|

Afghanistan |

17,057 |

26% |

|

Syria |

11,104 |

17% |

|

Yemen |

5,339 |

8% |

|

Libya |

3,457 |

5% |

|

Ukraine |

3,108 |

5% |

|

Myanmar |

2,978 |

5% |

|

Colombia |

2,862 |

4% |

|

Pakistan |

2,288 |

3% |

|

Mali |

1,955 |

3% |

|

Iraq |

1,639 |

2% |

|

Nigeria |

1,487 |

2% |

|

Cambodia |

1,159 |

2% |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold.

From the Russian invasion on 24 February through mid-September 2022, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recorded 277 civilian mine/ERW casualties in Ukraine, compared to 58 in 2021.[128] This already represents a fivefold increase. The HALO Trust recorded 169 civilian casualties from explosive devices in Ukraine from 25 February to 12 July 2022, noting it was considered as “a significant under-representation of actual statistics.”[129] The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) reported that during the first seven weeks of the conflict, there were 102 casualties (29 killed and 73 injured) among deminers.[130]

Casualty demographics[131]

The long-recognized trend of civilian harm caused by mines/ERW continued to be apparent in 2021, with civilians accounting for the vast majority of casualties.[132] In 2021, 76% of all casualties were civilians, where their status was known; while the Monitor identified 27 casualties among deminers in seven countries and one other area.[133]

The country with the most civilian casualties was Afghanistan (1,073), followed by Syria (760), Yemen (455), Myanmar (344), Nigeria (206), and Iraq (180); together representing 72% of the total civilian casualties recorded in 2021.

Military personnel or other combatants represented 23% of all casualties. The country with the most military casualties was Syria (465), followed by Nigeria (256) and Mali (175); together making up 69% of the total military casualties recorded in 2021.[134]

Civilian status of casualties in 2021

|

Civilian |

4,200 |

|

Deminer |

27 |

|

Military |

1,298 |

|

Unknown |

19 |

At least 1,696 child casualties were recorded in 2021. Children made up half (50%) of civilian casualties where the age group was known (3,418), accounting for 40% of all casualties where the age group was known (4,275).[135] Children were killed (636) or injured (1,057) by mines/ERW in 33 states and two other areas.[136] The survival outcome for three children was not reported. In 2021, as in previous years, the vast majority of child casualties were boys (77%).[137] ERW remained the item causing most child casualties (741, or 44%), followed by improvised mines (372, or 22%), and unspecified mine types (331, or 20%).[138]

As in previous years, men and boys made up the majority of recorded casualties in 2021, accounting for 2,675 (or 81%) of casualties where the sex was known (3,292). Women and girls accounted for 617 (or 19%).

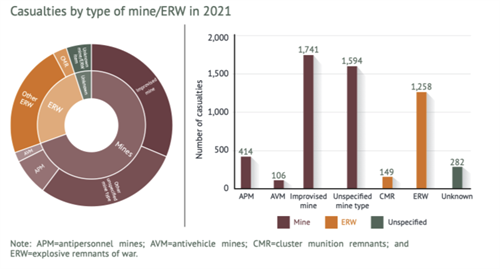

Casualties by device type

In 2021, improvised mines, most of which are believed to act as antipersonnel mines, accounted for the highest number of casualties for the sixth consecutive year.

Collectively, landmines of all types caused the vast majority of recorded casualties (3,855, or 70%) in 2021—including factory-made antipersonnel mines (414, or 7%), victim-activated improvised mines (1,741, or 31%), antivehicle mines (106, or 2%), and unspecified landmine types (1,594, or 29%). Most casualties attributed to unspecified mine types in 2021 were reported in Syria (925) and Yemen (384), which both have significant numbers of casualties due to improvised mine use. Together, Syria and Yemen accounted for 82% of casualties due to unspecified mine types in 2021.

Cluster munition remnants caused 149 casualties, while other ERW caused 1,258 casualties in 2021. A total of 282 casualties resulted from mines/ERW that were not disaggregated.

Casualties and Mine Ban Treaty status in 2021

Mine/ERW casualties were recorded in 36 States Parties in 2021, representing over two-thirds (62%, or 3,454) of annual casualties. Six States Parties each recorded more than 100 casualties.

States Parties with over 100 casualties in 2021

|

State Party |

Casualties |

|

Afghanistan |

1,074 |

|

Yemen |

528 |

|

Nigeria |

462 |

|

Mali |

252 |

|

Iraq |

224 |

|

Colombia |

152 |

The trend of declining annual casualties in most States Parties since the entry into force of the treaty continued, aside from those experiencing conflict and substantial improvised mine use.

During 2021, the Monitor recorded a total of 2,034 mine/ERW casualties in 11 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, with some 60% of those casualties recorded in Syria (1,227).[139] For the fourth year running, Myanmar accounted for the next highest casualty total among states yet to join the treaty, with 368 casualties; an increase on the 280 recorded in 2020.

In three other areas—Nagorno-Karabakh, Somaliland, and Western Sahara—a combined total of 56 casualties were reported in 2021.[140]

Recording casualties

Many mine/ERW casualties go unrecorded each year globally, and therefore are not captured in the Monitor data. Some countries do not have functional casualty surveillance systems in place, while other forms of reporting are often inadequate or lack disaggregation.

- States Parties

In Afghanistan, data collection was constrained amid ongoing conflict. The existing system records only civilian casualties, with no reliable data on military casualties since 2019.

In Ethiopia, no disaggregated casualty data was available for 2021. In October 2021, the Global Protection Cluster reported 71 casualties caused by explosive ordnance in Ethiopia “in recent months.”[141]

Data on casualties of IEDs that are command-detonated (and therefore not landmines) is often included in generalized reporting and estimates, which can lead to discrepancies in the number of mine/ERW casualties reported. For example, the Monitor recorded 55 mine/ERW casualties in Somalia for 2021, while SEMA similarly reported 48 casualties. Yet the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNISOM) stated that there had been 669 casualties of “improvised explosive devices and explosive remnants of war” in the country during 2021.[142]

Yemen reported that it has no nationwide casualty surveillance system. Casualties have been recorded in an ad hoc manner amid ongoing fighting.[143] The Monitor recorded 528 mine/ERW casualties in the country in 2021, while Yemen reported 558 casualties for 2021 in its Article 7 report.[144] In 2022, it was reported that violence had reduced sharply in Yemen since a truce in October 2021, but that “the number of people injured or killed by landmines and unexploded ordnance remained the same or higher, highlighting the dangers of these remnants of war even in peace time.”[145]

- States not party and other areas

Determining total casualties in state not party Azerbaijan and in other area Nagorno-Karabakh, in 2021, was complicated by changes in the territorial control of mine/ERW affected areas. The Monitor recorded 61 casualties in Azerbaijan and 30 in Nagorno-Karabakh (including civilians, Armenian deminers, Azerbaijani military personnel, and Russian peacekeepers). In December 2021, the Prosecutor General’s Office of Azerbaijan reported that there had been 189 casualties since the end of the conflict on 10 November 2020, in the “liberated territories” of Azerbaijan (in Nagorno-Karabakh and Zangezur). It reported that 36 people were killed (29 civilians and seven military personnel) and 153 injured (44 civilians and 109 military personnel).[146]

In state not party Libya, despite a lack of casualty surveillance, 51 casualties were recorded in 2021. In Tripoli, it was reported that casualties were caused by mines, including manufactured and improvised antipersonnel landmines left by forces that withdrew from the city in mid-2020. Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Libyan media reported some 90 casualties from May 2021–March 2022. Five of the casualties were reported to be involved in clearance activities.[147]

Since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, annual casualty totals for state not party Syria have fluctuated due to inconsistent availability of data and sources, and a lack of access to affected areas. Annual totals for Syria are likely a considerable undercount. Ambiguity in media reports often leaves it unclear if mines involved in incidents were of an improvised nature. The Monitor’s casualty data for Syria is adjusted as new surveys and historical data become available.

Addressing The Impact

Mine clearance in 2021

The Mine Ban Treaty obligates each State Party to destroy—or ensure the destruction of—all antipersonnel landmines in mined areas under their jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after the entry into force of the treaty for that State Party.

Among States Parties, total reported clearance during 2021 was 132.52km².[148] This represents a decrease from the reported 146km² cleared in 2020. At least 117,863 landmines were cleared and destroyed in 2021.

Monitor data on clearance in States Parties is based on analysis of multiple sources, including reporting by national mine action programs, Article 7 reports, and Article 5 extension requests. In cases where varying annual clearance data is reported by States Parties, details are provided in footnotes and more information can be found in country profiles on the Monitor website.

Non-technical and technical survey also contribute to the overall amount of land that is released and returned to local populations for productive use. During 2021, some 276km² of land was released by States Parties, about half of which was released by clearance operations. A total of 26.15km² was reduced through technical survey and 117.33km² canceled via non-technical survey.

Antipersonnel mine clearance in 2020–2021[149]

|

State Party |

2020 |

2021 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

24.24 |

5,379 |

17.69 |

7,652 |

|

Angola |

1.77 |

452 |

5.91 |

3,617 |

|

BiH |

0.29 |

1,357 |

0.06 |

1,717 |

|

Cambodia |

46.42 |

10,085 |

43.73 |

6,087 |

|

Chad |

0.21 |

39 |

1.45 |

15 |

|

Chile |

0.60 |

12,526 |

Clearance completed in 2020 |

|

|

Colombia |

1.08 |

166 |

1.94 |

204 |

|

Croatia |

49.66 |

4,953 |

34.49 |

1,462 |

|

Cyprus* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

DRC |

0.02 |

23 |

0.01 |

12 |

|

Ecuador |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Eritrea |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Ethiopia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Iraq |

7.66 |

4,043 |

11.07 |

4,831 |

|

Mali |

N/R |

5 |

N/R |

16 |

|

Mauritania |

0 |

0 |

0.1 |

13 |

|

Niger |

0.01 |

115 |

0 |

7 |

|

Nigeria |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Oman |

0.23 |

0 |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Palestine |

0.01 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

|

Peru |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

188 |

|

Senegal |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Serbia |

0.27 |

0 |

0.29 |

9 |

|

Somalia |

**0.77 |

1 |

**0.25 |

13 |

|

South Sudan |

0.71 |

246 |

0.25 |

31 |

|

Sri Lanka |

4.59 |

43,157 |

4.10 |

26,804 |

|

Sudan |

0.35 |

42 |

0.03 |

17 |

|

Tajikistan |

0.65 |

5,106 |

0.37 |

2,219 |

|

Thailand |

0.92 |

9,355 |

0.53 |

19,002 |

|

Türkiye |

0.14 |

9,781 |

0.41 |

14,125 |

|

Ukraine |

N/R |

5 |

**2.90 |

N/R |

|

UK |

0.23 |

432 |

Clearance completed in 2020 |

|

|

Yemen |

**2.80 |

1,388 |

***4.49 |

3,365 |

|

Zimbabwe |

2.41 |

26,911 |

2.44 |

26,457 |

|

Total |

146.04 |

135,583 |

132.52 |

117,863 |

Note: APM=antipersonnel mines; and N/R=not reported.

*Cyprus states that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under Cypriot control.

**Clearance of mixed/undifferentiated contamination that included antipersonnel mines.

***Reported as cleared and reduced.

Based on reported data, Cambodia cleared the most land during 2021 (43.73km²), followed by Croatia (34.49km²). Sri Lanka cleared and destroyed the most landmines in 2021, with 26,804 cleared from 4.1km² of land. Thailand, Türkiye, and Zimbabwe all cleared a large number of antipersonnel mines from relatively small areas, indicating the density of mine-laying in their contaminated border areas.

Eleven States Parties cleared under 1km² in 2021: BiH, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mauritania, Peru, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Türkiye. Most of these states have contamination classified as small or medium and should be able to complete clearance within the next few years if clearance and land release outputs are increased.[150]

Nigeria’s Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Mine Ban Treaty has announced its intention to establish a national mine action center and humanitarian mine action program, and has requested UNMAS support.[151]

Improvised mines were reported cleared in 2021 in States Parties Afghanistan, Colombia, Iraq, Mali, Niger, Tajikistan, Türkiye, and Yemen.

Afghanistan released a total of 14.29km² of land contaminated with improvised mines, clearing 352 improvised mines.[152] All mines cleared in Colombia were improvised mines.[153] Iraq cleared 9.75km² of land contaminated with IEDs and destroyed 1,057 improvised mines.[154] Only one improvised mine was cleared in Tajikistan in 2021, close to the border with Afghanistan. Türkiye cleared 103 improvised mines as part of security operations by military counter-IED teams.[155] Yemen cleared 2,439 IEDs, though it was not specified how many of these were improvised mines.[156] The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported the clearance of 16 improvised mines in Mali and seven improvised mines in Niger.[157]

A number of States Parties with Article 5 obligations did not undertake clearance in 2021: Cyprus, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, Palestine, and Senegal.[159]

Cyprus reported that it did not undertake clearance as no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remained under its control.[160] Ecuador reported that clearance was suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021.[161] Guinea-Bissau had not yet re-started operations following the discovery of new contamination in 2021, and was working to re-build the capacity required to resume survey and clearance operations.[162]

Ethiopia has not provided any new figures for antipersonnel mine clearance since its Article 7 report for January 2019–April 2020, when it reported 1.75km² cleared and 128 antipersonnel mines destroyed.[163] As of March 2021, Ethiopia reported that it had cleared 0.05m² in Fiq district in the Somali region, and 46 antivehicle mines were cleared, but no antipersonnel mines were cleared and destroyed.[164]

Eritrea has not reported any clearance since it last submitted an updated Article 7 transparency report in 2014.[165]Niger was granted an Article 5 extension in 2020, but undertook no clearance or survey in 2021, citing a lack of resources and external support, climatic conditions, and insecurity.[166]

Palestine reported no clearance or survey during 2021 and destroyed no antipersonnel mines.[167]

No clearance has taken place in Senegal since 2017, though non-technical survey was carried out in February–March 2020, releasing 26 areas in Bignona department.[168] It was reported that no contamination was found. The COVID-19 pandemic, security concerns, and limited funding resulted in the suspension of non-technical survey in the country.[169]

As of October 2022, eight States Parties with Article 5 obligations had not submitted updated Article 7 reports to outline their progress on clearance.[170] In addition, three States Parties suspected to have improvised mine contamination—Cameroon, Mali, and Venezuela—have not provided an updated Article 7 report for two or more consecutive years.

Article 5 deadlines and extension requests

If a State Party believes that it will be unable to clear and destroy all antipersonnel landmines contaminating its territory within 10 years after entry into force of the Mine Ban Treaty for the country, it is able to request an extension under Article 5 for a period of up to 10 years.

- Progress to 2025

At the Third Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty in Maputo, in June 2014, States Parties agreed to “intensify their efforts to complete their respective time-bound obligations with the urgency that the completion work requires.” This included a commitment “to clear all mined areas as soon as possible, to the fullest extent by 2025.”

As of October 2022, a total of 23 States Parties had deadlines to meet their Article 5 obligations before or no later than 2025. Nine States Parties have Article 5 deadlines later than 2025.

States Parties with clearance deadlines beyond 2025

|

Clearance deadline |

States Parties |

|

2026 |

Croatia, Mauritania, Senegal, South Sudan |

|

2027 |

BiH, Somalia |

|

2028 |

Iraq, Palestine, Sri Lanka |

In 2022, four States Parties—Afghanistan, Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, and Serbia—requested extensions to their clearance deadlines up to 2025; while four—Argentina, Sudan, Thailand, and Yemen—requested extensions beyond 2025.

It appears that few of the States Parties with deadlines in 2025 or earlier will be able to complete clearance within their deadlines. Only Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe appear to be on track to meet their Article 5 deadlines. In 2022, Sri Lanka drafted a new mine action strategy and set a new completion date of 2027.[171] Zimbabwe reported that it is on target to meet its 2025 clearance deadline, with only 38% of known contamination left to clear, and half the extension period remaining.[172]

It was expected that Oman was on track to complete clearance with a plan to re-clear seven areas from February 2021 to April 2024.[173] Yet as of October 2022, Oman had not submitted an Article 7 report to update States Parties on its progress.

Angola’s annual land release since 2019 has been below the projected annual land release of 17km² in its 2019–2025 workplan.[174] Angola, and clearance operators working in the country, have said that additional investment is required to complete clearance.[175]

Cambodia and Croatia are not on track to meet their Article 5 deadlines unless they can increase clearance capacity. Cambodia has said that it will meet its Article 5 deadline and has launched an appeal for public and private funding to contribute to this effort.[176] Yet agreeing demarcation of border areas with Thailand remains a challenge that could delay progress.

The DRC and South Sudan both report that they are on track to meet their clearance deadlines, but ongoing insecurity is a concern in both countries.[177] The DRC’s clearance output has been limited and some areas remain to be surveyed.

Clearance output in States Parties BiH, Chad, Niger, and Peru has been small, while no clearance has taken place in Senegal since 2017. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and a lack of financing are cited as key reasons for this lack of progress.[178] Chad, Niger, Peru, and Senegal all have relatively small areas left to clear and should be able to complete clearance within their deadlines if the pace of clearance is accelerated. BiH has massive contamination but has only cleared 2.56km² since 2017.

Iraq is unlikely to meet its Article 5 deadline due to the extent of contamination and its priority to clear improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in areas liberated from the Islamic State group.[179] Mauritania has reported a lack of funding as being the main barrier to meeting its deadline.[180] Tajikistan reported that current capacity would need to be increased to meet its deadline.[181] It is unclear if Somalia, which was granted an extension in 2021, will meet its Article 5 deadline.

Ongoing conflict and insecurity are likely to impact the ability of Colombia, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Ukraine to meet their deadlines. Colombia reported that it will not meet its deadline due to ongoing use of improvised mines by non-stated armed groups (NSAGs).[182] In Ethiopia, there has been little progress on clearance and survey over the last two years. In Nigeria, conflict in the northeast has hindered the mapping of contamination and restricted survey and clearance activities.[183] Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukraine did not have control of parts of the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, impeding its ability to clear contaminated areas in these territories.[184] Ongoing hostilities in 2022 have added to the extent of contamination and prevented access for clearance.

Summary of Article 5 deadline extension requests

|

State Party |

Original deadline |

Extension period (no. of request) |

Current deadline |

Status |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2013 |

10 years (1st)

|

1 March 2023 |

Requested extension until 1 March 2025 (2 years) |

|

Angola |

1 January 2013 |

5 years (1st) 8 years (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target

|

|

Argentina* |

1 March 2010 |

10 years (1st) 3 years (2nd) |

1 March 2023 |

Requested extension until 1 March 2026 (3 years) |

|

BiH |

1 March 2009 |

10 years (1st) 2 years (2nd) 6 years (3rd) |

1 March 2027 |

Behind target |

|

Cambodia |

1 January 2010 |

10 years (1st) 6 years (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Chad |

1 November 2009 |

1 year and 2 months (1st) 3 years (2nd) 6 years (3rd) 5 years (4th) |

1 January 2025 |

Behind target

|

|

Colombia |

1 March 2011 |

10 years (1st) 4 years and 10 months (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Expected to request another extension |

|

Croatia |

1 March 2009 |

10 years (1st) 7 years (2nd) |

1 March 2026 |

Behind target |

|

Cyprus |

1 July 2013 |

3 years (1st) 3 years (2nd) 3 years (3rd) 3 years (4th) |

1 July 2025 |

Expected to request another extension |

|

DRC |

1 November 2012 |

2 years and 2 months (1st) 6 years (2nd) 1 year and 6 months (3rd) 3 years and 6 months (4th) |

31 December 2025 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Ecuador |

1 October 2009 |

8 years (1st) 3 months (2nd) 5 years (3rd) |

31 December 2022 |

Requested extension until 31 December 2025 (3 years) |

|

Eritrea |

1 February 2012 |

3 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 11 months (3rd) |

31 December 2020 |

In violation of the treaty by not requesting a new extension |

|

Ethiopia |

1 June 2015 |

5 years (1st) 5 years and 7 months (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

1 November 2011 |

2 months (1st) 1 year (2nd) |

31 December 2022 |

Requested extension until 31 December 2024 (2 years) |

|

Iraq |

1 February 2018 |

10 years (1st) |

1 February 2028 |

Behind target |

|

Mauritania |

1 January 2011 |

5 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 1 year (3rd) 5 years (4th)

|

31 December 2026 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Niger |

1 September 2009 |

2 years (1st) 1 year (2nd) 5 years (3rd) 4 years (4th) |

31 December 2024 |

Behind target |

|

Nigeria |

1 March 2012 |

1 year (1st) 4 years (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Oman |

1 February 2025 |

N/A |

1 February 2025 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Palestine |

1 June 2028 |

N/A |

1 June 2028 |

Behind target |

|

Peru |

1 March 2009 |

8 years (1st) 7 years and 10 months (2nd) |

31 December 2024 |

Behind target |

|

Senegal |

1 March 2009 |

7 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 5 years (3rd) |

1 March 2026 |

Behind target |

|

Serbia |

1 March 2014 |

5 years (1st) 4 years (2nd) |

1 March 2023 |

Requested an extension until 1 December 2024 (1 year and 9 months) |

|

Somalia |

1 October 2022 |

5 years (1st) |

1 October 2027 |

Behind target |

|

South Sudan |

9 July 2021 |

5 years (1st) |

9 July 2026 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Sri Lanka |

1 June 2028 |

N/A |

1 June 2028 |

On target |

|

Sudan |

1 April 2014 |

5 years (1st) 4 years (2nd) |

1 April 2023 |

Requested extension until 1 April 2027 (4 years) |

|

Tajikistan |

1 April 2010 |

10 years (1st) 5 years and 9 months (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Thailand |

1 May 2009 |

9 years and 6 months (1st) 5 years (2nd) |

31 October 2023 |

Requested extension until 31 December 2026 (3 years and 2 months) |

|

Türkiye |

1 March 2014 |

8 years (1st) 3 years and 10 months (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Likely to request another extension |

|

Ukraine |

1 June 2016 |

5 years (1st) 2 years and 6 months (2nd) |

1 December 2023 |

Behind target |

|

Yemen |

1 March 2009 |

6 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 3 years (3rd) |

1 March 2023 |

Requested extension until 1 March 2028 (5 years) |

|

Zimbabwe |

1 March 2009 |

1 year and 10 months (1st) 2 years (2nd) 2 years (3rd) 3 years (4th) 8 years (5th) |

31 December 2025 |

On target |

Note: N/A=not applicable.

*Argentina and the UK both claim sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. The UK completed mine clearance of the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas in 2020, but Argentina has not yet acknowledged completion.

- Extension requests submitted in 2021 and 2022

In 2021, seven States Parties were granted an extension to their Article 5 clearance deadlines: Cyprus, the DRC, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Nigeria, Somalia, and Türkiye. For two of these—Mauritania and Somalia—the extended deadline goes beyond 2025.

In 2022, eight States Parties submitted requests to extend their Article 5 clearance deadlines: Afghanistan, Argentina, Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, Serbia, Sudan, Thailand, and Yemen. Decisions on these requests will be made at the Twentieth Meeting of States Parties in November 2022.

On 4 July 2022, the Permanent Mission of Afghanistan to the United Nations (UN) in Geneva submitted a request to extend Afghanistan’s clearance deadline for two years until March 2025. It was expected that a further detailed request for an extension would be submitted in March 2024. Due to the complexity of the political situation in the country, details on the remaining challenge or an accompanying workplan could not be included in the request.[185]

Argentina submitted an extension request for three years until 1 March 2026. Argentina has cited the need to verify clearance of the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas completed by the United Kingdom (UK) in 2020 to comply with its obligations under the treaty.[186]

Ecuador has requested an extension of three years until 31 December 2025 to clear remaining contamination of 0.04km². This is Ecuador’s fourth extension request. However, little progress has been made, with no clearance taking place in 2020 and 2021. The remaining contaminated areas are in high altitude locations with challenging climatic conditions.

Guinea-Bissau reported the discovery of new mined areas in 2021 and was given an extension until 31 December 2022, with the objective to mobilize resources to carry out survey and develop an evidence-based action plan. Yet little progress was made due to lack of resources.[187] In 2022, Guinea-Bissau requested a further extension to 31 December 2024 to conduct survey, and to enable a request to be submitted in March 2024 outlining a clearance plan.[188]

Serbia submitted a third extension request in 2022, requesting 21 additional months until 1 December 2025 to clear 0.56km² and to survey and clear newly discovered suspected mined areas in Bujanovac municipality. Serbia stated that it would be able to provide an updated workplan by the Twenty-First Meeting of States Parties in November 2023.[189]

Sudan also submitted a third extension request in 2022, for four additional years until 1 April 2027.[190] As of December 2021, Sudan had identified 102 hazardous areas totaling 13.28km².[191] As a result of the Juba peace talks, Sudan’s mine action program had access to previously inaccessible areas and expected to identify new hazardous areas close to the frontlines.

Thailand submitted a third extension request in 2022, for three years and two months until 31 December 2026.[192] While on target in terms of its survey and clearance plan, a primary reason given for the delay was a lack of access to 14.31km² of contaminated land on the border with Cambodia which had not yet been demarcated.[193] The COVID-19 pandemic had also prevented face-to-face bilateral meetings to negotiate border clearance. Thailand asserted that it would be able to complete all clearance by its October 2023 deadline if access was not an obstacle.[194]

Yemen has requested a fourth extension, for five years until March 2028, to continue with its baseline survey to determine the extent and impact of new mine contamination. Yet it appears unlikely that five years will be sufficient for Yemen to meet its Article 5 clearance obligations. It is hoped that the baseline survey can be expanded if the security situation improves.

Risk education is a core pillar of humanitarian mine action and a key aspect of the legal obligations under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty. The treaty requires States Parties to “provide an immediate and effective warning to the population” in all areas under their jurisdiction or control in which antipersonnel mines are known or suspected to be emplaced.

Risk education has often been under-reported in transparency reports or at treaty’s meetings in lieu of updates on clearance and survey.[195] Yet delivery of risk education to affected populations is a primary and often cost-effective means of preventing injuries and saving lives.

Adopted by States Parties in 2019, the Oslo Action Plan includes a dedicated section on risk education and contains five actions points for States Parties on risk education. This has contributed to a renewed attention for this pillar in recent years. These actions include:

- Integrating risk education within wider humanitarian, development, protection, and education efforts, and with other mine action activities;

- Providing context-specific risk education to all affected populations and at-risk groups;

- Prioritizing people most at risk through analysis of available casualty and contamination data, and through an understanding of people’s behavior and movements;

- Building national capacity to deliver risk education, which can adapt to changing needs and contexts; and

- Reporting on risk education in annual Article 7 transparency reports.[196]

In addition, the Oslo Action Plan requires States Parties to provide detailed, costed, and multiyear plans for context-specific mine risk education and reduction in affected communities.

Provision of risk education in 2021

In 2021, 30 States Parties were known to have provided risk education to populations at risk due to antipersonnel landmine contamination. States Parties Cameroon, Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, Oman, and Peru reported no risk education in 2021.

States Parties which provided risk education in 2021

|

Afghanistan Angola BiH Burkina Faso Cambodia Chad Colombia Croatia Cyprus DRC |

Eritrea Ethiopia Iraq Mali Mauritania Niger Nigeria Palestine Senegal Serbia |

Somalia South Sudan Sri Lanka Sudan Tajikistan Thailand Türkiye Ukraine Yemen Zimbabwe |

Risk education continued to be disrupted in some states due to the COVID-19 pandemic during 2021. For the second year running, a joint risk education campaign carried out by Ecuador and Peru in contaminated border areas was not held, with funding diverted to other priorities.[197]

In Angola, Cambodia, Iraq, Somalia, South Sudan, Thailand, and Zimbabwe, in-person risk education sessions continued in 2021, but with restrictions on the number of people who could attend.[198] In Angola, physical distancing and masks were still used.[199] In Cambodia, Iraq, and Zimbabwe, schools remained closed for much of the year, preventing risk education in those settings.[200] South Sudan stopped distributing leaflets, to prevent the spread of the virus.[201]

Thailand and Zimbabwe reported fewer risk education beneficiaries in 2021 compared to 2020, as large events were canceled amid the COVID-19 pandemic.[202]

Risk education reporting and planning

In 2021, only eight of the 22 States Parties which provided updates on risk education in their Article 7 reports, included full details on risk education activities conducted, with beneficiary data disaggregated by sex and age: Angola, Cambodia, Colombia, Iraq, South Sudan, Sudan, Thailand, and Zimbabwe. Guinea-Bissau conducted no risk education in 2021, but reported on plans for 2022. The remaining 13 states provided less detailed information in their transparency reports.[203]

Of the States Parties that had submitted updated Article 7 reports for activities in 2021, Burkina Faso, Cyprus, Niger, and Tajikistan did not report on risk education. However, risk education was conducted in all four countries.

In Burkina Faso, UNMAS provided risk education to affected communities and military personnel on the threat from improvised mines.[204] In Cyprus, UNMAS delivered risk awareness training to the police and military contingents of the UN peacekeeping mission during their induction training.[205] In Tajikistan, risk education was carried out by the Tajikistan National Mine Action Center (TNMAC), the Red Crescent Society of Tajikistan, and by the Union of Sappers.[206] Niger has not provided any updates on risk education since 2012, but UNMAS provided risk education to humanitarian personnel working in areas contaminated by improvised mines.[207]

As of October 2022, Afghanistan, BiH, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Eritrea, Mali, Nigeria, Palestine, Somalia, and Ukraine had not submitted Article 7 reports for 2021; though risk education was conducted in each of these states, with the exception of Cameroon.

Of the Article 5 extension requests submitted in 2022, only those submitted by Guinea-Bissau and Sudan contained detailed, costed, and multiyear plans for context-specific risk education. Ecuador, Serbia, Thailand, and Yemen confirmed that risk education would be conducted, but did not provide a budget or workplan for implementation. Afghanistan did not submit a detailed extension request. Risk education was not relevant to the extension request of Argentina, which requested time to verify clearance completed by the UK in the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas.

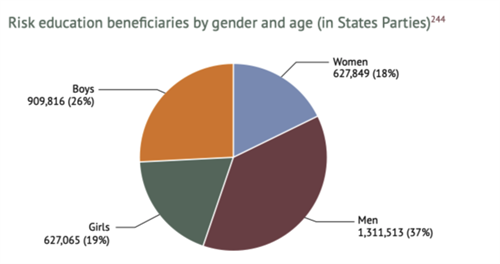

Risk education prioritization

Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) victim data informed national risk education prioritization and planning in all States Parties where IMSMA was used in 2021. Thirteen States Parties reported having a prioritization mechanism in place in 2021, for targeting risk education activities.[208]