Cluster Munition Monitor 2015

Contamination and Clearance

Cluster Munition Remnant Survey (CMRS) team, searching for cluster munition footprint in Kornmom district, Ranakiri province, Cambodia.

© NPA Cambodia, June 2015

Contamination and Clearance

(Jump to Contamination and land release)

Overview[1]

As of July 2015, a total of 25 states and other areas are contaminated by cluster munition remnants (nine States Parties, two signatories, 11 non-signatories, and three other areas).[2] It is unclear whether a further three States Parties, two signatories, and two non-signatories are contaminated by cluster munition remnants.[3] New use since the Convention on Cluster Munitions came into force in August 2010 has resulted in further contamination in six non-signatories: Cambodia, Libya, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. In addition, non-signatory Ukraine became contaminated for the first time after the convention entered into force. The threat to civilians and the socioeconomic impact is a particular cause for concern in: Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, Somalia, Vietnam, and Yemen, as well as Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara.

To address the risks posed by these weapons, eight States Parties have already completed clearance of areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants: Albania, the Republic of the Congo, Grenada, Guinea-Bissau, Malta, Mauritania, Norway, and Zambia. One signatory, Uganda, and one non-signatory, Thailand, have also completed clearance of areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants.

Most other states continue land release efforts. Between 2010 and 2014, a total of more than 255km2 of land was cleared and 295,000 submunitions destroyed. Approximately 74km2 of land was cleared and 69,000 submunitions destroyed during 2014. Five States Parties, one signatory, four non-signatories, and two other areas have reported land release through technical survey, non-technical survey, or both since the convention entered into force.[4]

However, these estimates are based on incomplete data.[5] Survey and clearance results have been poorly recorded and reported in many states. Therefore a clear picture is not available of the scale of contamination, the amount of land released through survey and clearance, and the number of submunitions destroyed.

Conflict and insecurity impeded land release efforts in 2014 and 2015 in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

|

Clearance obligations under Article 4 Under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, each State Party is obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention. If unable to complete clearance in time, a state may request an extension of the deadline for periods of up to five years. The first clearance deadline is 1 August 2020. In seeking to fulfill their clearance and destruction obligations, affected States Parties are required to:

At the Second Meeting of States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions in September 2011, States Parties agreed to encourage the implementation of recommendations submitted by Australia on the use of all appropriate methods to release land that is deemed not to be contaminated.[6] Norway, as President of the Third Meeting of States Parties, submitted a paper entitled “Compliance with Article 4” to the Fourth Meeting of States Parties. The paper’s stated aim was to explain the key obligations that states must fulfill in order to be able to make a declaration of compliance. Ireland and Lao PDR, as Co-Coordinators of the Working Group on Clearance and Risk Reduction Education, submitted to the same meeting a paper entitled “Effective steps for the clearance of cluster munition remnants.” States Parties “warmly welcomed” both documents.[7] |

Clearance completed

Eight States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions have completed clearance of cluster munition-contaminated areas or declared that they no longer have any cluster munition remnants: Albania, Republic of the Congo, Grenada, Guinea-Bissau, Malta, Mauritania, Norway, and Zambia.

In addition, signatory Uganda completed clearance of cluster munition-contaminated areas in 2008, while non-signatory Thailand completed clearing cluster munition remnants in 2011.

Improving clearance efficiency: land release

Survey methodologies in mine action have evolved over the last two decades in order to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the removal of the threat of explosive remnants of war (ERW), including cluster munition remnants. In the 1990s and 2000s, many surveys were conducted that lacked technical expertise and resulted in a significant overestimation of the problem. This, along with insufficient technical survey, led to reports of large quantities of uncontaminated land being cleared at considerable expense.

The International Mine Action Standard (IMAS) for Land Release was introduced in June 2009 to address this. The definition of land release is “the process of applying all reasonable effort to identify, define, and remove all presence and suspicion of mines/ERW through non-technical survey, technical survey and/or clearance. The criteria for ‘all reasonable effort’ shall be defined by the National Mine Action Authority (NMAA).”[8]

A set of guiding principles for the land release of cluster munition-contaminated areas was published by the CMC in June 2011. It calls for affected states to invest sufficient resources into properly identifying cluster munition-affected areas before carrying out clearance. It recommends states conduct a desk assessment of ground conditions, weapons delivery systems, battlefield data, etc., followed by non-technical survey to collect field evidence of contamination and, where required, technical survey to define a cluster strike footprint. It notes clearing cluster munitions should not be approached in the same way as clearing landmines and suggests states apply principles detailed in the IMAS battle area clearance (BAC)[9] standards (09.11) for land contaminated exclusively with cluster munition remnants.[10]

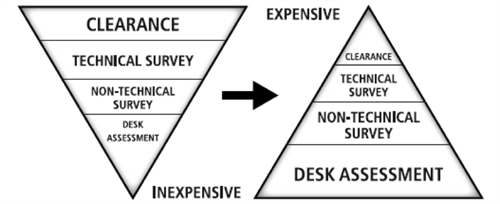

Evolution of land release

The two pyramids depict evolution of land release, indicating improved operational efficiency. It is derived from graphic provided courtesy of the Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD).

|

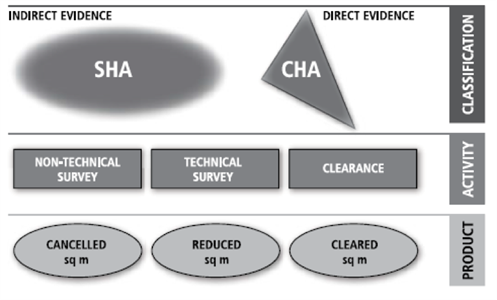

Land release terminology Specific IMAS terminology used for referring to contamination, survey, and clearance activities includes:[11]

Land release process

Derived from graphic provided courtesy of the Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD). |

To promote more efficient release of land, amendments to IMAS were adopted in April 2013 to the general assessment standards (formerly 08.10). These amendments set out to simplify and clarify standards on land release (now 07.11), non-technical survey (now 08.10), and technical survey (now 08.20).

It is beyond the scope of this overview to evaluate how land release methodologies have been used and the extent to which clearance of cluster munition contamination has become more efficient. Such an assessment would need to consider several factors, such as: how funding and mine action resources have been used; how many submunitions have been destroyed per square kilometer cleared; and the context in which mine action operations have been conducted.

Nevertheless, it is possible to report a positive trend toward using land release methodologies. Since 2010, five States Parties, one signatory, four non-signatories, and two other areas have reported releasing land through survey, thereby avoiding unnecessary clearance costs.[14] In Lao PDR, Norwegian People’s Aid’s (NPA) Cluster Munition Remnants Survey (CMRS) is now recognized by the mine action authority, the National Regulatory Authority (NRA), and has been adopted by all NGOs as “evidence based survey.”[15] However, in several states there still appear to be instances of clearance being conducted without evidence of contamination.[16]

Progress under the Vientiane Action Plan

The Vientiane Action Plan adopted by States Parties at the Convention on Cluster Munitions First Meeting of States Parties in Vientiane, Lao PDR, 9–12 November 2010 seeks to ensure effective and timely implementation of the convention’s provisions. Section V (Actions #10–#19) is related to “Clearance and destruction of cluster munition remnants and risk reduction activities.”[17] This section examines the progress of States Parties related to clearance and destruction of cluster munition remnants.[18]

Action #10 calls on States to increase their capacities for clearance. The extent to which States Parties have increased their capacities for clearance is unclear as existing information about resources allocated to cluster munition clearance, improvements in clearance efficiency, and clearance rates is insufficient. However, Lao PDR has demonstrated a sharp upward annual trend in clearance rates, with double the annual rate of clearance in 2014 as that in 2010. Croatia and BiH have also shown an upward trend from 2010 to 2014. Croatia expected clearance capacity to increase in 2015 due to increased funding.[19] However, a lack of funding is reported to hinder progress in tackling cluster munition remnants in Afghanistan, Chad, Lebanon, and Montenegro.[20]

Action #12 calls on States Parties to “endeavour to, within one year of entry into force for that State Party, identify as precisely as possible locations and size of all cluster munition contaminated areas under their jurisdiction or control.” As of 1 August 2015, only BiH, Croatia, and Montenegro have provided an indication of the location and size of their cluster munition-contaminated areas. Lao PDR and Iraq are among the most contaminated states in the world, but are unable to give a realistic estimate of their contamination. Afghanistan and Lebanon have provided figures for known SHAs, but there may be other unknown or unconfirmed areas.[21] Chile, Germany, and the United Kingdom (UK) have areas that are suspected to contain cluster munition remnants, but have not conducted survey to define the area—the UK’s suspected areas are located within known minefields. Mozambique is in the process of confirming that it no longer has suspected cluster munition-contaminated areas.[22]

Action #13 calls for the development and implementation of national clearance plans. While Croatia lacks a specific plan and BiH’s plan has not yet been endorsed by the government,[23] both states demonstrate progress toward completing their clearance obligations. Afghanistan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Montenegro have plans in place to clear cluster munition remnants, but progress is slow due to lack of capacity and, in the case of Afghanistan, security conditions.[24] Iraq, Chad, Chile, Germany, and the UK have not presented comprehensive plans with timelines for survey and clearance.

Action #15 calls for the application of non-technical survey, technical survey, and clearance, which constitute land release methodologies. Standards or standard operating procedures specifically related to cluster munition remnants were approved in Lao PDR in early 2015,[25] and are being developed in BiH and Mozambique.[26] By 2015, five States Parties had reported some cancellation or reduction of land through survey.[27] No survey has yet been conducted in Chad or Chile, while the situation in Iraq is unclear.

Action #16 calls on States Parties to “provide annually precise and comprehensive information on the size and location of cluster munition contaminated areas released. This information should be disaggregated by release methods.” Discrepancies exist for almost all countries, in at least one year, between the data provided by different sources: the Article 7 reports, the national mine action centers, and mine action operators. There are major gaps in reporting from Iraq, while Chad has provided no reports. Some operators in Afghanistan, Lao PDR, and Iraq do not disaggregate data on submunition clearance and destruction from other mine clearance and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD)[28] activities.

Action #18 calls for all States Parties to ensure that they fulfill their obligations under Article 4 as expeditiously as possible, and that the least number of States Parties possible will be compelled to request an extension. Of the nine States Parties with known cluster munition contamination, three appear to be on track to meet their deadlines: BiH, Croatia, and Montenegro.[29] Lebanon may not meet its deadline, as progress has fallen short of its planning targets.[30] Afghanistan may be able to meet its deadline, but notes that clearance in some areas is subject to appropriate security conditions.[31] Lao PDR and Iraq are highly unlikely to be able to meet their deadlines due to the scale of the problem, insufficient data to define the problem, the lack of a comprehensive plan, and capacity, and, in the case of Iraq, ongoing conflict. In the cases of Chile and Germany, it is unclear whether they will meet their deadline, as neither state has provided a comprehensive plan. The same is true of the UK, one of three countries where contamination is unclear. Of the remaining two, Mozambique is in the process of confirming it is free of contamination and Chad lacks a comprehensive survey to define the problem.

Action #19 calls on States Parties to promote the achievement of clearance goals and the identification of clearance needs. As of August 2015, Chad had yet to submit an Article 7 transparency report; the first one was due in 2014. Chile submitted its last report in 2012, and Lebanon in 2014. In 2014, there were discrepancies between Article 7 reports and data provided by other sources in Afghanistan, BiH, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon.

Clearance in conflict

In 2014 and 2015, conflict has hindered land release activities in two States Parties (Afghanistan and Iraq), and seven non-signatories (Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen). Not only is clearance of cluster munition remnants impeded, but the contamination exacerbates the impact of conflict on civilians. Refugees and internally displaced persons may face danger from cluster munition remnants while on the move and when they resettle or return home. Access to vital services and livelihoods, already impeded by conflict, may be even further constrained by cluster munition contamination.

Afghanistan, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen report that some cluster munition-contaminated areas cannot be accessed due to insecurity or conflict. In Iraq, it was reported that escalating conflict between Iraq and the non-state armed group Islamic State in the second half of 2014 forced the temporary suspension of operations in some areas, and drew army demining and EOD capacity away from operations in the south. Most of Syria is inaccessible to clearance operators. In Libya, international mine action actors withdrew after the conflict escalated in July 2014.

Conflict impedes the functioning of mine action programs. No mine action program exists in Syria, while in Libya the program is impaired by the lack of a functioning government. In Yemen it was reported that the conflict in 2014 and 2015 had affected the mine action center’s ability to fulfill its role.[32]

In March 2015, the UN reported that the ongoing conflict in South Sudan had resulted in the suspension of all evaluation of progress under the National Mine Action Strategic Plan for 2012–16.[33] Sudan’s mine action plan for 2013–2019 was designed in light of the overall security situation, capacity for mine action, and types of assets available.[34]

In Syria and Libya, clearance has frequently been conducted immediately after fighting has occurred, by non-state armed groups and volunteers, often lacking adequate training and resources. In Ukraine, clearance has been conducted by local authorities on both sides of the conflict, usually immediately after cluster munition contamination has occurred, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) recommended that a national mine authority and center appropriate to a conflict setting be established.[35]

Contamination and land release

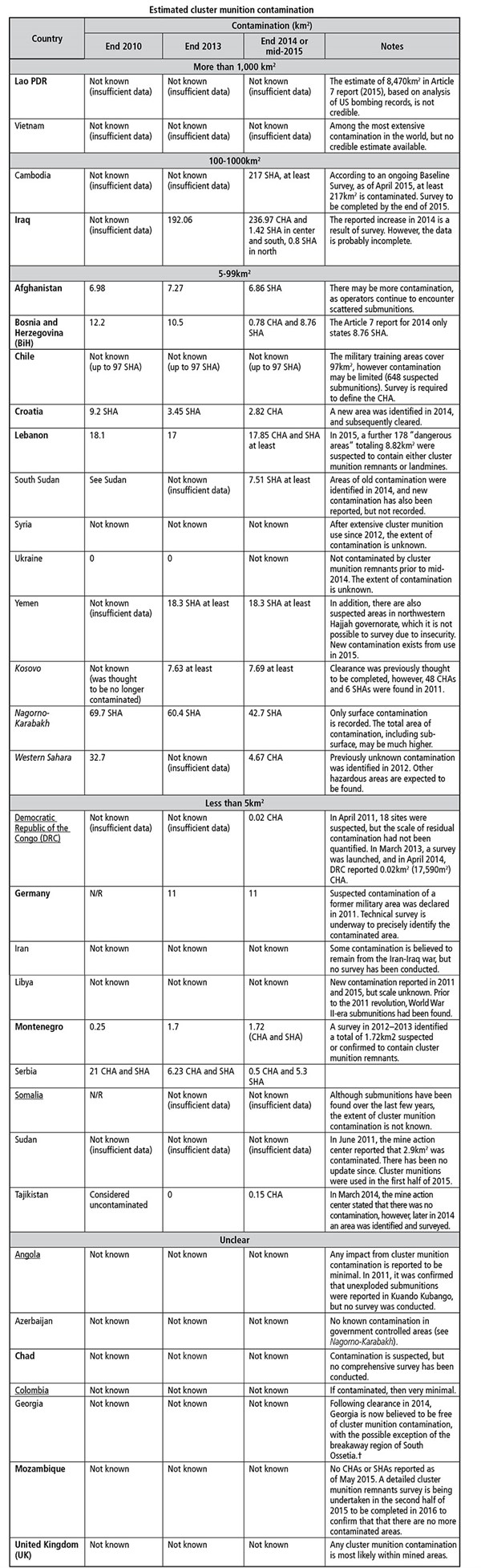

It is difficult to present an accurate picture of global cluster munition contamination given the shortcomings in reporting on both the scale of contamination and on land release efforts. The tables below therefore provide only an indication of the situation and highlight weaknesses in the data. Please see the relevant mine action country profiles online for detailed information and sources.[36]

Contamination statistics

The size of cluster munition-contaminated areas is not known in several countries due to a lack of survey and poor data collection and management. The data contained in the following table is drawn from various sources—those that appear to be most accurate and complete have been used.

The cases where the reported size of area contaminated by cluster munitions has increased, or stayed roughly the same despite clearance, are usually due to the identification of previously unknown or unsurveyed areas. This is the case in Croatia, Iraq, Lebanon, and Tajikistan, as well as Kosovo and Western Sahara.

The new contamination resulting from conflict since the Convention on Cluster Munitions came into force has not been surveyed and quantified, with the exception of Cambodia.[37]

Note: States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions are indicated in bold; conventionsignatories are underlined; other areas are in italics; N/R = Not reported. *ICBL, “Country Profile: Georgia: Mine Ban Policy,” 1 October 2012, the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2012/georgia/mine-ban-policy.aspx.

Note: States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions are indicated in bold; conventionsignatories are underlined; other areas are in italics; N/R = Not reported. *ICBL, “Country Profile: Georgia: Mine Ban Policy,” 1 October 2012, the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2012/georgia/mine-ban-policy.aspx.

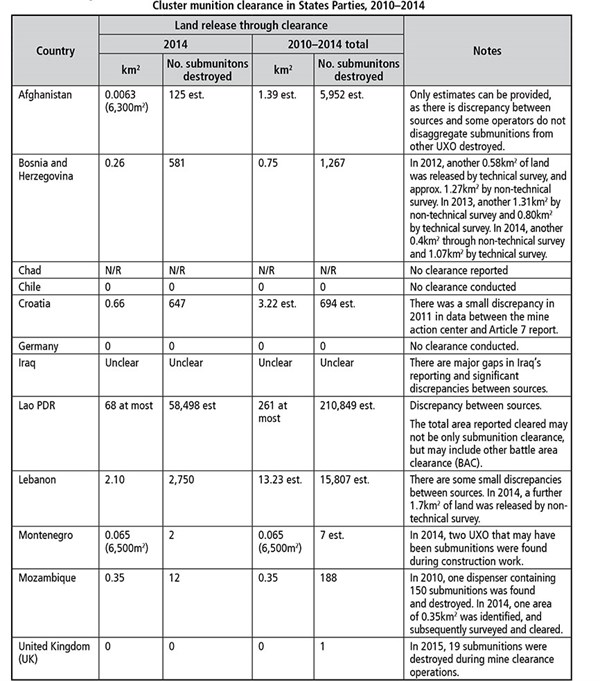

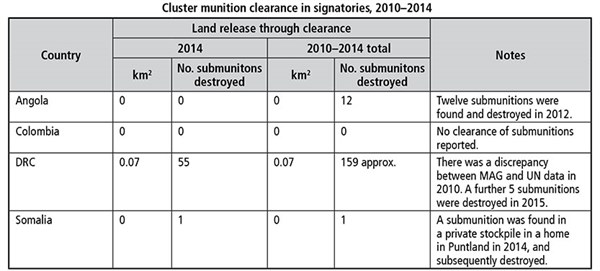

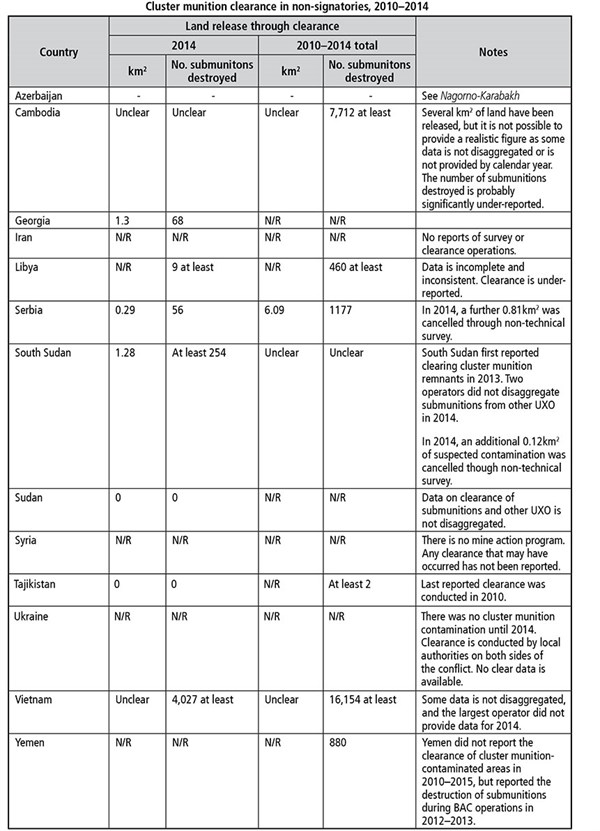

Land release statistics

The information provided in the table below draws on data provided in Article 7 transparency reports, national programs, and mine action operators. There are sometimes discrepancies between these sources. Where this is the case, the data that appears to be most reliable is used and a note has been made. Among the countries that reported clearance, those for which the results were most unclear were States Parties Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lao PDR; non-signatories Cambodia, Libya, South Sudan, Sudan, and Vietnam; as well as the area of Kosovo.

This section provides information on land release by clearance and, where data is available, land release by technical and non-technical survey (see text box for an explanation of land release terminology).

Where destruction of submunitions was reported, but no area was reported to be released, this was usually the result of BAC or roving EOD.

Note: N/R = Not reported.

Note: N/R = Not reported.

Note: N/R = Not reported.

Five-year country summaries on contamination and clearance

States Parties

Afghanistan’s cluster munition contamination dates from use by Soviet and United States (US) forces and blocks access to agricultural and grazing land.[38] Most cluster munitions used by the US in late 2001 and early 2002 were removed during clearance operations in 2002–2003 guided by US airstrike data.[39] The total area of 6.86km2 suspected to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants at of the end of 2014, is similar to the figure reported five years earlier.[40] In 2013, operators said they continued to find random submunitions during demining operations.[41] Afghanistan reported in 2014 that clearance was severely hampered by a shortage of funds and security problems.[42] Five long-established national NGOs and two international NGOs conducted clearance in 2014 and 2015.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s cluster munition contamination results from Yugoslav use in the 1992–1995 conflict after the break-up off the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Additionally, cluster munitions were used by NATO forces in Republika Srpska.[43] In 2011, the first phase of a general survey identified 12.18 km2 SHA, of which 3.23 km2 was believed to be high risk.[44] As of April 2015, BiH’s contamination is spread across 10 cantons.[45] In 2014 and 2015, land release has been conducted by the BHMAC, NPA, the Armed Forces, and the Civil Protection.[46]

Chad is believed to be contaminated by cluster munitions used by France and Libya in the 1980s, but the full extent of contamination is unknown and only a few submunitions have been found by clearance operators in the north.[47] Chad stated in 2013 that the Tibesti region in the northwest of the country was being surveyed, but has provided no further information since then.[48] The National Demining Center (Centre National de Déminage, CND) operates demining and EOD teams.[49] The only international operators that have been present in the last five years are Minetech and MAG.[50] No clearance of cluster munition remnants has been reported over the last five years.

Chile has reported three military training areas totalling 97km2 that are suspected to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants. No survey has been conducted as of June 2015.[51]

Croatia is contaminated by cluster munitions used in the 1990s conflict that followed the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia.[52] The contaminated area reduced from 9.2km2 suspected hazardous area in 2010 to 2.82km2 confirmed by the end of 2014, across five counties, although new contamination was found in the intervening period.[53] Many of the contaminated areas “are used for cattle breeding and are close to settlements.”[54] State-owned MUNGOS conducted the majority of clearance in 2014, while commercial demining companies conducted other clearance-related tasks.[55]

Germany reported in June 2011 that it had identified areas suspected of containing cluster munition remnants at a former Soviet military training range at Wittstock in Brandenburg. Non-technical survey resulted in a suspected area of approximately 11km2.[56] The area is completely perimeter marked with warning signs and an official directive constrains access to it.[57] In June 2015, Germany stated a technical survey of the area is underway, but did not provide information on the expected timeframe for survey or clearance operations.[58]

The extent of Iraq’s cluster munition contamination is not known with any degree of accuracy. As of December 2014, surveys identified 237km2 CHA,[59] but this data is probably incomplete. Heavy contamination exists in central and southern Iraq as a result of extensive use by the US in 1991 and 2003.[60] In addition, cluster munition remnants were found in 2010 from strikes launched by coalition forces around Dohuk in the north in 1991.[61] In 2010, submunition contamination was reported to be a significant problem, more so than mines.[62] Clearance is conducted by NGOs, commercial operators, the army, and the civil defence. Operations over the last five years have been hampered by insecurity and bureaucratic problems.

Lao PDR is the world’s most heavily contaminated state as a result of cluster bombs used by the US between 1964 and 1973, including more than 270 million submunitions.[63] There is no agreed estimate of the full extent of contamination, but 14 of the country’s 17 provinces and a quarter of all villages are reported to be UXO-contaminated.[64] Submunitions are reported to be the most common form of remaining ERW contamination and are responsible for close to 30% of all incidents, with a significant economic impact.[65] In 2014, submunitions accounted for 21 out of the 45 casualties reported.[66] The National Regulatory Authority (NRA) approved a new standard for evidence-based survey in late 2014 and survey is being conducted, with development and resettlement areas identified as initial survey priorities.[67] UXO Lao (the country’s biggest operator), five international NGOs, and several national and international commercial operators conducted clearance operations in 2014. Lao PDR has also been training the army for a role in mine action since 2012.[68]

Lebanon’s four southern regions are affected by contamination resulting from Israeli use of cluster munitions during the July–August 2006 conflict, while some parts of the country are also contaminated by cluster munitions used in the 1980s.[69] Cluster munition remnants continue to affect agriculture.[70] Of approximately 57.8km2 of contaminated area that has reportedly affected Lebanon as of December 2014, an estimated 17.85km2 remains to be released. Additionally, a further 8.82km2 is suspected to contain either cluster munition or mine contamination.[71] Slow clearance progress has been attributed to funding shortfalls, and the identification of previously unreported contaminated areas.[72] Since 2010, clearance has been conducted by the Lebanese Armed Forces and national and international NGOs.

Montenegro’s cluster munition contamination is the result of NATO airstrikes in 1999.[73] Montenegro initially reported in 2011 that it had no contaminated areas, but later that year confirmed that submunitions were found in 2007.[74] A non-technical survey conducted in 2012–2013 identified approximately 1.7km2 suspected and confirmed contaminated areas in two municipalities and one urban municipality.[75] The contamination mainly affects infrastructure and utilities, accounting for 63% of the affected land, with agriculture accounting for another 30%. One area remains unsurveyed as it was inaccessible due to bad weather conditions.[76] Funding has not yet been secured to undertake technical survey and clearance of the contaminated areas.[77]

Mozambique stated in 2014 that there was limited use of cluster munitions during its civil war.[78] Clearance operators have cleared and destroyed cluster munition remnants over the past five years during BAC and EOD operations. In 2014, a CHA of 0.35km2 in Cahora-Bassa district, Tete province, was identified and subsequently cleared.[79] As of May 2015 there were no known hazardous areas. In 2015, Mozambique has been undertaking a survey to confirm that areas already cleared do not contain any submunitions.[80] The completion date for this survey and clearance is 2016.[81]

United Kingdom. There may be an unknown number of cluster munition remnants on the Falkland Islands/Malvinas as a result of use of cluster bombs by the UK against Argentine positions in 1982. Most cluster munition contamination was cleared in the first year after the conflict.[82] In 2015, 19 submunitions were destroyed during mine clearance operations. The UK affirmed in 2015 that no known areas of cluster munition remnants exist outside suspected hazardous areas on the islands, in particular mined areas, which are all marked and fenced.[83]

Non-signatories with more than 5km2 of contaminated land

Cambodia’s cluster munition contamination is the result of the intensive US air campaign during the Vietnam War that concentrated on the country’s northeastern provinces along its border with Lao PDR and Vietnam.[84] In 2011, Thailand fired cluster munitions into Cambodia’s northern Preah Vihear province, which resulted in additional contamination of approximately 1.5 km2.[85] The full extent of the country’s contamination is unknown.[86] Since 2012, a baseline survey of seven eastern provinces had identified almost 217km2 of suspected cluster munition contamination by April 2015, almost half located in one province, Stung Treng. The survey was expected to be completed by the end of 2015.[87] Land release has been conducted by the Cambodian Mine Action Centre (CMAC) and international NGOs.

All 10 of South Sudan’s states experienced cluster munition use at some point, as operators have identified cluster munition remnants since 2006. As of 2015, nine states are still contaminated, particularly Central, Eastern, and Western Equatorial states.[88] Further areas of contamination were identified in 2014 from use prior to independence, as well as new use since December 2013.[89] Access to contaminated areas in Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile states has been extremely limited due to instability and fighting and this is severely impeding efforts to confirm or address contamination.[90] Four international operators reported clearing cluster munition remnants in 2014.

Syria. Syrian government forces have used cluster munitions extensively since 2012, while non-state armed group Islamic State also used cluster munitions in the second half of 2014. Cluster munitions have been used in at least 10 of Syria’s 14 governorates, but the extent of contamination is not known.[91] Prior to the current conflict, the Golan Heights was contaminated by UXO, including unexploded submuntions. There is no functioning mine action program in Syria in government- or opposition-controlled areas. In 2012, UNMAS opened and then closed an office in Damascus.[92] Government and opposition armed forces as well as civilians conduct some clearance on an ad hoc basis.[93]

Ukraine. The full extent of contamination from cluster munition rockets used by both government and pro-Russian armed opposition forces in Ukraine’s eastern provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk from mid-2014 until a February 2015 ceasefire is not known. Prior to 2014, cluster munitions had never been used in Ukraine. Both Ukrainian government authorities and opposition groups have conducted clearance of ERW including cluster munition remnants, usually reacting after attacks have taken place, or when community members notify authorities of remnants and suspected contamination.[94]

Vietnam is one of the most cluster munition-contaminated countries in the world as a result of the US use in 1965–1973 in 55 provinces and cities.[95] The US military also abandoned substantial quantities of cluster munitions.[96] There is no accurate assessment of contamination and no clear data on land release. The Army Engineering Corps has conducted most clearance in the country over the past five years, while several NGOs conduct clearance including BAC and roving EOD. According to the Engineering Command, it would need to at least double the number of clearance teams in order to meet a 2013–2015 National Mine Action Plan released in May 2013 that calls for clearance of 1,000km2 a year, prioritizing clearance of provinces with the highest levels of contamination and casualties.[97]

Yemen. Much of the contamination is in areas of ongoing conflict and the full extent is not known. There are some 18km2 of suspected submunitions in the northern Saada governorate but it has not been possible to survey other suspected areas in the northwestern Hajjah governorate.[98] Contamination results from use in 2009 and perhaps earlier. The extent of new contamination arising in 2015 has not been determined, resulting from air strikes by the Saudi-led coalition on Ansar Allah (the Houthi), most notably in Saada.[99] All survey and clearance is conducted by the Yemen Mine Action Centre (YEMAC), however it did not report results for operations in 2014. Escalating political turmoil and conflict in 2014 together with a lack of funding have impaired YEMAC’s abilities to discharge its responsibilities.[100]

Other areas with more than 5km2 of contaminated land

Kosovo is affected by cluster munitions used by Federal Republic of Yugoslavia armed forces in 1998–1999 and by a NATO air campaign in 1999.[101] After demining operations finished in 2001, the UN reported the problem virtually eliminated.[102] However, subsequent surveys since 2008 have identified uncleared areas.[103] Clearance has been conducted by NGOs, the Kosovo Security Forces, and NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR).

Nagorno-Karabakh’s cluster munition contamination dates from the conflict in 1988–1994 and affects all regions with more than 75% of the contamination located in three regions: Askeran, Martuni, and Martakert.[104] HALO has been the only operator since 2000. Cluster munition remnants contamination decreased significantly during 2014, as a result of clearance operations.[105] In 2011 it was reported that cluster munition sites run through villages and contaminated gardens and prime agricultural land.[106] Despite a clear humanitarian need, the international isolation of Nagorno-Karabakh is reported to make it difficult to raise funds.[107]

Western Sahara. Morocco used cluster munitions against Polisario Front forces from 1975 to 1991. Western Sahara was expected to complete the clearance of known cluster munition remnants outside the buffer zone with the Moroccan beam (sand wall) by the end of 2012.[108] However, the target date could not be met after the discovery of previously unknown contaminated areas.[109] Additional strike sites may be identified from information provided by the local population.[110]

[1] The Monitor acknowledges the contributions of Norwegian People's Aid (NPA), which conducted the majority of mine action research performed in 2015 and shared it with the Monitor. The Monitor is responsible for the findings presented here.

[2] See tables below for details. States Parties: Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chile, Croatia, Germany, Lao PDR, Iraq, Lebanon, and Montenegro; signatories: Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Somalia; non-signatories: Cambodia, Iran, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Vietnam, and Yemen; and other areas: Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara.

[3] See tables below for details. States Parties: Chad, Mozambique, and the United Kingdom (UK); signatories: Angola and Colombia; and non-signatories: Azerbaijan and Georgia.

[4] States Parties: BiH, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Montenegro, and Mozambique; signatory: DRC; non-signatories: Cambodia, Serbia, South Sudan, and Tajikistan; and other areas: Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara.

[5] In several countries, the amount of land cleared of cluster munition remnants has not been disaggregated from the clearance of landmines and/or other unexploded countries. As Lao PDR has high clearance rates, its total battle area clearance (BAC) has been adjusted pro rata for clearance of cluster munition remnants compared to other forms of unexploded ordnance.

[6] See, statement of Australia, “Application of all available methods for the efficient implementation of Article 4,” CCM/MSP/2011/W.P.4, 15 July 2011.

[7] Final Document, Fourth Meeting of States Parties, CCM/MSP/2013/6, 23 September 2014, p. 4.

[8] International Mine Action Standard (IMAS) 07.11 “Land Release,” First Edition (Amendment 2, March 2013), p. 3.

[9] According to IMAS, battle area clearance refers to "the systematic and controlled clearance of dangerous areas where the explosive hazards are known not to include landmines."

[10] “CMC Guiding Principles for Implementing Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions,” June 2011.

[11] International Mine Action Standard 07.11 “Land Release,” First Edition (Amendment 2, March 2013), pp. 3–4.

[12] See, Glossary of Terms, available on Monitor website, the-monitor.org/en-gb/the-issues/glossary.aspx.

[13] Ibid.

[14] States Parties: BiH, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Montenegro, and Mozambique; signatory: DRC; non-signatories: Cambodia, Serbia, South Sudan, and Tajikistan; and other areas: Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara.

[15] NPA, Cluster Munition Remnants: Methods of Survey and Clearance (August 2014); NRA Announcement No. 004/NRAB, 21 January 2015; and, interview with Phoukhieo Chanthasomboune, Director, NRA, Vientiane, 28 April 2015.

[16] For example, most clearance in non-signatory Vietnam does not appear to be based on evidence of contamination. The Army Engineering Corps reports large areas released (45km2 released in 2012, and 1,000km2 cleared in 2013), but provides no information on the numbers of submunitions or other UXO found and destroyed, nor the use of either non-technical or technical survey.

[17] “Vientiane Action Plan,” Convention on Cluster Munitions, as adopted at the final plenary meeting on 12 November 2010.

[18] Action points 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, and 19 are related to clearance. The other action points are related to risk reduction activities.

[19] Email from Miljenko Vahtarić, Assistant Director for International Cooperation and Education, Croatian Mine Action Centre, 27 April 2015.

[20] Afghanistan, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (calendar year 2014), Form F, 28 April 2015; presentation of Chad, African Union/ICRC Weapons Contamination Workshop, Addis Ababa, 3–5 March 2013; Third Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 2 May 2013, p.12; statement of Chad, Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference, Maputo, June 2014; Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC), “Mid-term Review to Strategy 2011–2020, Milestone 2013,” August 2014; and email from Darvin Lisica, Programme Manager, BiH, NPA, 3 March 2015. Article 7 reports available at bit.ly/MonitorArt7ClusterMunitions and meeting statements generally available under "Work Programme and Meetings" at www.clusterconvention.org.

[21] Interviews with Mine Action Coordination Centre of Afghanistan (MACCA) implementing partners, Kabul, May 2013; response to NPA questionnaire by Brig.-Gen. Elie Nassif, LMAC, 12 May 2015; and email, 2 July 2015.

[22] Response to NPA questionnaire by the IND, 30 April 2015; and statement by Alberto Maverengue Augusto, IND, Fifth Meeting of States Parties, 4 September 2014.

[23] BiH Mine Action Centre (BHMAC), “Revision of Mine Action Strategy in Bosnia and Herzegovina 2009-2019 (First Revision 2012),” 14 March 2013; and, UNDP, Draft Mine Action Governance and Management Assessment for Bosnia and Herzegovina, 13 May 2015, p. 17.

[24] Afghanistan, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (calendar year 2014), 28 April 2015, Form F; “Safe Path Forward II,” Lao PDR, 22 June 2012; LMAC, “Lebanon Mine Action Strategy 2011–2020,” September 2011, p. 4; response to Monitor questionnaire by Brig.-Gen. Imad Odiemi, LMAC, 2 May 2014; response to Monitor questionnaire by Amela Balik, NPA, 3 March 2014; and email from Darvin Lisica, NPA, 3 March 2015.

[25] NRA Announcement No. 004/NRAB, 21 January 2015.

[26] “Revision of Mine Action Strategy in Bosnia and Herzegovina 2009–2019 (First Revision – 2012),” Sarajevo, March 2013, p. 12; statement of Mozambique, Convention on Cluster Munitions Fourth Meeting of States Parties, Lusaka, 12 September 2013; and response to NPA questionnaire by the IND, 30 April 2015.

[27] BiH, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Montenegro, and Mozambique.

[28] Explosive ordnance disposal: the detection, identification, evaluation, render safe, recovery, and disposal of explosive ordnance.

[29] Response to NPA questionnaire by the IND, 30 April 2015; and statement by Alberto Maverengue Augusto, IND, Fifth Meeting of States Parties, 4 September 2014.

[30] LMAC, “Mid-term Review to Strategy 2011–2020, Milestone 2013,” August 2014.

[31] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (calendar year 2014), Form F, 28 April 2015.

[32] Interviews with mine action stakeholders requesting anonymity, February−June 2015.

[33] Response to NPA questionnaire by Robert Thompson, UNMAS, 30 March 2015.

[34] Revised Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 30 July 2013, pp. 28–33.

[35] OSCE, “ERW clearance in a conflict setting,” presentation by Anton Shevchenko, 16 February 2015.

[36] Available on the Monitor website at the-monitor.org/cp.

[37] Aina Ostreng, “Norwegian People’s Aid clears cluster bombs after clash in Cambodia,” NPA, 19 May 2011, http://bit.ly/MonitorCMM15Clearancef37.

[38] Statement of Afghanistan, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 15 April 2013.

[39] Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Landmine Action, Banning Cluster Munitions: Government Policy and Practice (Mines Action Canada, Ottawa, May 2009), p. 27; and interviews with demining operators, Kabul, 12–18 June 2010.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Interviews with MACCA implementing partners, Kabul, May 2013.

[42] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2014), Form F, 28 April 2015.

[43] NPA, “Implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” Sarajevo, undated but 2010, provided by email from Darvin Lisica, NPA, 3 June 2010. See also country profile for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[44] NPA, “Cluster Munitions Remnants in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A General Survey of Contamination and Impact,” 2011, p. 21.

[45] Emails from Tarik Serak, Head, Department for Mine Action Management, BHMAC, 23 April 2015; and Amela Balic, Operations Manager, NPA Bosnia, 15 April 2015.

[46] Email from Tarik Serak, BHMAC, 23 April 2015.

[47] Handicap International (HI), Fatal Footprint: The Global Human Impact of Cluster Munitions (Brussels, 2006), p. 17; HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels, 2007), p. 48; Survey Action Centre, “Landmine Impact Survey, Republic of Chad,” Washington, DC, 2002, p. 59; HRW and Landmine Action, Banning Cluster Munitions: Government Policy and Practice (Mines Action Canada, Ottawa, 2009), p. 56; and emails from Liebeschitz Rodolphe, UNDP, 21 February 2011; and from Bruno Bouchardy, MAG Chad, 11 March 2011.

[48] Statement of Chad, Convention on Cluster Munitions Third Meeting of States Parties, Oslo, 13 September 2012.

[49] ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Chad: Mine Action,” 14 August 2014, the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2014/chad/mine-action.aspx.

[50] Landmine and Cluster Munition Report 2011–2015.

[51] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, September 2012; and email from Juan Pablo Rosso, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 16 June 2015.

[52] CROMAC, “Mine Action in Croatia and Mine Situation,” www.hcr.hr/en/minSituac.asp.

[53] Emails from Miljenko Vahtarić, Assistant Director for International Cooperation and Education, CROMAC, 27 April and 10 June 2015.

[54] Ibid., 27 April 2015.

[55] Ibid., 27 April and 10 June 2015.

[56] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2014), Form F, 20 April 2015.

[57] Ibid.; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form G, 4 April 2012.

[58] Interview with Volker Boehm, Deputy Head of Mission, Permanent Mission of Germany to the Conference on Disarmament, Geneva, 25 June 2015.

[59] Data provided by Ahmed al-Jasim, Head, Information Management, Department of Mine Action, 8 July 2015.

[60] UNICEF/UNDP, “Overview of Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War in Iraq,” June 2009, p. 10.

[61] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Mark Thompson, Country Programme Manager, MAG, 23 July 2011.

[62] UNICEF/UNDP, “Overview of Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War in Iraq,” June 2009, p. 10.

[63] “US bombing records in Laos, 1964–73, Congressional Record,” 14 May 1975; NRA, “UXO Sector Annual Report 2009,” Vientiane, undated but 2010, p. 13; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2013), Form F.

[64] NRA, “UXO Sector Annual Report 2012,” undated but 2013, p. 5.

[65] Ibid.; and “Hazardous Ground, Cluster Munitions and UXO in the Lao PDR,” UNDP, Vientiane, October 2008, p. 8.

[66] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (calendar year 2014), Form H; and email from Bountao Chanthavongsa, NRA, 3 August 2015.

[67] NRA Announcement No. 004/NRAB, 21 January 2015; and interview with Phoukhieo Chanthasomboune, NRA, Vientiane, 28 April 2015.

[68] Interview with Phoukhieo Chanthasomboune, NRA, Vientiane, 28 April 2015.

[69] LMAC, “Lebanon Mine Action Strategy 2011–2020,” September 2011; and responses to NPA questionnaire by Brig.-Gen. Elie Nassif, LMAC, 12 May and 17 June 2015.

[70] MAG, “Cluster Munition Contamination in Lebanon using survey data,” September 2014, p. 4.

[71] Response to NPA questionnaire by Brig.-Gen. Elie Nassif, LMAC, 12 May 2015; and email, 2 July 2015.

[72] LMAC, “Mid-term Review to Strategy 2011–2020, Milestone 2013,” August 2014.

[73] NPA, “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, p. 21.

[74] Article 7 Report (for 1 August 2010 to 27 January 2011), Form F; and telephone interviews with Veselin Mijajlovic, Director, Regional Centre for Divers Training and Underwater Demining (RCUD), 19 and 25 July 2011.

[75] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2014), Form F; Article 7 Report (for 2013), Form F; and NPA, “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, p. 26. There is a discrepancy in the locations reported as contaminated between the Article 7 reports and NPA.

[76] Email from Veselin Mijajlovic, RCUD, 16 June 2015.

[77] Email from Darvin Lisica, NPA, 3 March 2015.

[78] Statement by Alberto Maverengue Augusto, IND, Convention on Cluster Munitions Fifth Meeting of States Parties, San José, 4 September 2014.

[79] Ibid.; and responses to NPA questionnaire by the IND, 30 April 2015; and APOPO, 15 May 2015.

[80] Response to NPA questionnaire by Afedra Robert Iga, Advisor, Capacity Building Project Mozambique, NPA, 4 June 2015.

[81] Response to NPA questionnaire by the IND, 30 April 2015.

[82] Letter to Landmine Action from Lt.-Col. Scott Malina-Derben, Ministry of Defence, 6 February 2009.

[83] Email from Jeremy Wilmshurst, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 1 July 2015.

[84] South East Asia Air Sortie Database, cited in D. McCracken, “National Explosive Remnants of War Study, Cambodia,” NPA in collaboration with Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA), Phnom Penh, March 2006, p. 15; HRW, “Cluster Munitions in the Asia-Pacific Region,” April 2008, www.hrw.org/legacy/pub/2008/arms/CMC.ClusterMunitions.Asia-Pacific.2008.pdf; and HI, Fatal Footprint: The Global Human Impact of Cluster Munitions (HI, Brussels, November 2006), p. 11.

[85] Aina Ostreng, “Norwegian People’s Aid clears cluster bombs after clash in Cambodia,” NPA, 19 May 2011, http://bit.ly/MonitorCMM15Clearancef37.

[86] South East Asia Air Sortie Database, cited in D. McCracken, “National Explosive Remnants of War Study, Cambodia,” NPA in collaboration with CMAA, Phnom Penh, March 2006, p. 15; HRW, “Cluster Munitions in the Asia-Pacific Region,” April 2008, www.hrw.org/legacy/pub/2008/arms/CMC.ClusterMunitions.Asia-Pacific.2008.pdf; and HI, Fatal Footprint: The Global Human Impact of Cluster Munitions (HI, Brussels, November 2006), p. 11.

[87] NPA Cambodia PowerPoint presentation, undated but May 2015, received by email from Jan Erik Stoa, Programme Manager, NPA, 1 June 2015.

[88] Response to NPA questionnaire by Robert Thompson, UNMAS, 30 March 2015; and email, 12 May 2014.

[89] UNMAS, “About UNMAS in South Sudan,” updated March 2014, www.mineaction.org/programmes/southsudan.

[90] Response to NPA questionnaire by Robert Thompson, UNMAS, 30 March 2015.

[91] HRW, “Technical Briefing Note: Use of cluster munitions in Syria,” 4 April 2014. The governorates were Aleppo, Damascus City and Rural Damascus, Daraa, Deir al-Zour, Hama, Homs, Idlib, Latakia, and Raqqa.

[92] The office was established in March 2012, but then closed in August 2012. Emails from Flora Sutherland, Senior Programme Coordinator, UNMAS, New York, 28 May 2013, and 9 June 2015.

[93] Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor Syria Country Profile, 2014.

[94] Side-event presentation by Mark Hiznay, HRW, in Geneva, February 2015; and interview, 18 February 2015.

[95] “Vietnam mine/ERW (including cluster munitions) contamination, impacts and clearance requirements,” presentation by Sr. Col. Phan Duc Tuan, People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), in Geneva, 30 June 2011.

[96] Interview with Sr. Col. Phan Duc Tuan, PAVN, in Geneva, 30 June 2011.

[97] Prime Minister’s Decision No. 738/QD-TTg, 13 May 2013; and interview with Sr. Col. Nguyen Thanh Ban, Engineering Command, Hanoi, 18 June 2013.

[98] Email from Ali al-Kadri, General Director, YEMAC, 20 March 2014.

[99] HRW, “Yemen: Saudi-Led Airstrikes Used Cluster Munitions,” 3 May 2015; and HRW, “Yemen: Cluster munitions harm civilians,” 31 May 2015.

[100] Interviews with mine action stakeholders requesting anonymity, February−June 2015.

[101] See UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), “UNMIK OKPCC EOD Management Section Annual Report 2005,” Pristina, 18 January 2006, p. 2; and ICRC “Explosive Remnants of War, Cluster Bombs and Landmines in Kosovo,” Geneva, revised June 2001, pp. 6 and 15, www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/misc/explosive-remnants-of-war-brochure-311201.htm.

[102] “UNMIK Mine Action Programme Annual Report – 2001,” Mine Action Coordination Cell, Pristina, undated but 2002, p. 1.

[103] HALO Trust, “Failing the Kosovars: The Hidden Impact and Threat from ERW,” 15 December 2006, p. 1.

[104] Email from Andrew Moore, Caucasus & Balkans Desk Officer, HALO Trust, 29 May 2015.

[105] Ibid

[106] Ibid., 5 March 2010, and 9 March 2011.

[107] “Were we work: Nagorno-Karabakh,” HALO website, undated, www.halotrust.org/where-we-work/nagorno-karabakh.

[108] Email from Karl Greenwood, Chief of Operations, Action on Armed Violence (AOAV)/Mechem Western Sahara Programme, AOAV, 18 June 2012.

[109] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Sarah Holland, MINURSO, 24 February 2014; and email from Gordan Novak, Senior Technical Advisor, AOAV Western Sahara, 25 July 2014.

[110] Email from Gordan Novak, AOAV Western Sahara, 25 July 2014.