Landmine Monitor 2011

Casualties and Victim Assistance

© Hafeez/SPADO, 3 January 2011

A survivor in Pakistan.

Casuaties in 2010 [1]

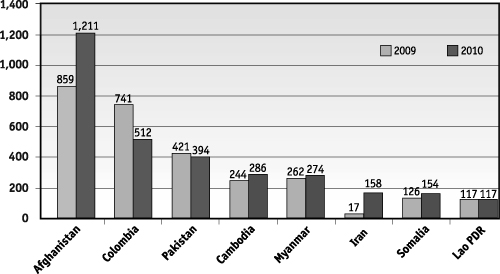

The Monitor identified 4,191 casualties occurring in 2010 that were caused by mines, victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs), cluster munition remnants,[2] and other explosive remnants of war (ERW) in 60 states and areas.[3] At least 1,155 people were killed and another 2,848 people were injured; for 188 casualties the outcome of the incident was unknown. Since 2008 the greatest number of casualties has been recorded in Afghanistan (1,211 in 2010) and Colombia (512 in 2010). The global casualty total in 2010 is almost the same as that recorded in 2009, when 4,010 casualties were identified.[4]

States with 100 or more casualties in 2010

|

State |

No. of casualties in 2009 |

|

Afghanistan |

1,211 |

|

Colombia |

512 |

|

Pakistan |

394 |

|

Cambodia |

286 |

|

Myanmar |

274 |

|

Iran |

158 |

|

Somalia |

154 |

|

Lao PDR |

117 |

As in previous years, Asia-Pacific had by far the greatest number of casualties; five of the eight countries with more than 100 casualties in 2010 were from the region.

2010 casualties by region

|

Region |

No. of casualties |

No. of states and areas in |

|

Asia-Pacific |

2,477 |

12 |

|

Americas |

524 |

3 |

|

Africa |

531 |

17 |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

427 |

13 |

|

Europe and CIS |

232 |

15 |

|

Total |

4,191 |

60 |

While the slight increase (5%) in recorded casualties from 2009 to 2010 was likely not indicative of a trend given the poor quality of casualty data in some countries, this was the first annual increase recorded by the Monitor since 2005. However, the total remained much lower than the 5,502 casualties recorded for 2008 and lower than any year since monitoring began in 1999. The small rise in recorded casualties was due in most part to increases in two countries with large numbers of annual casualties: Afghanistan and, to a lesser extent, Cambodia. In addition, significant increases in casualties were recorded in other countries with fewer casualties, such as Iran, Sudan, and Yemen. Increased casualty numbers in Sudan[5] and Yemen have been attributed to greater movement of people in hazardous areas, related to the escalation of armed violence. The increase in Iran was due to the availability of casualty data for 2010 that was not available for 2009.

These increases were somewhat offset by a continuing overall decline in annual casualty rates in most other countries, largely due to clearance and increased risk awareness. The continued trend of decreasing casualties in Colombia remained one of the major contributors to this global decline.[6] Overall, the number of states and areas recording casualties was fairly steady with a decrease of just four fewer states recording casualties in 2010 as compared with 2009, when 64 states and areas recorded casualties.[7]

It must be stressed that, as in previous years, the 4,191 figure only includes recorded casualties and, due to incomplete data collection, the true casualty total is definitely higher. Past reporting has indicated that hundreds or thousands more casualties occur, but are not captured by annual data. As in previous years, data collection in various countries such as Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), India, Iraq, Lao PDR, Libya, Myanmar, and Pakistan was believed to be incomplete due either to the lack of a functioning official data collection system and/or to the challenges posed by ongoing armed conflict.

Total mine/ERW casulaties for the most affected countries: 2009-2010

Casualty demographics

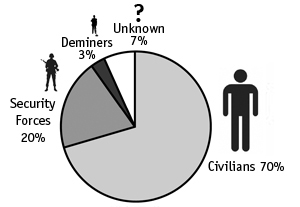

In 2010, civilians made up 75% of all casualties for which the civilian/military status was known (2,952 of 3,914).[8] This was an increase from 2009 when civilians made up 70% of all casualties. Three quarters of the military casualties recorded for 2010 were identified in just three states, where there was ongoing conflict or armed violence: Colombia (357), Pakistan (186), and Afghanistan (84).[9]

Mine/ERW casualties by civilian/military status: 2010

In 2010, the number of casualties among humanitarian clearance operators was double that recorded for 2009. There were 131 deminer[10] casualties (36 deminers killed; 95 injured) recorded in 15 states/areas[11] in 2010, compared to 67 deminer casualties in 2009. The large increase can mainly be attributed to the availability of casualty data from Iran, where there were 47 demining casualties recorded in 2010 and for which there was no data on demining casualties in 2009. However, there were also small increases in several other countries such as Germany (nine casualties);[12] Lebanon and Sudan, with seven casualties each; and Angola with six casualties. After Iran, Afghanistan recorded the second largest number of casualties from clearance accidents with 31 as compared with 34 in 2009. While most demining casualties involved nationals of the country where the demining took place, there were three casualties among British deminers working in Afghanistan (one) and Sudan (two).

As in previous years, the vast majority of casualties where the sex was known were male (88%); the other 12% were female.[13] Among civilian casualties for whom the sex was known, female casualties made up a larger proportion at 17% of the total (420 of 2,479). In 2010 there were no states where girls and/or women were the majority of casualties; for 25 states/areas with casualties in 2010, no female casualties were recorded.[14]

Mine/ERW casualties by sex: 2010

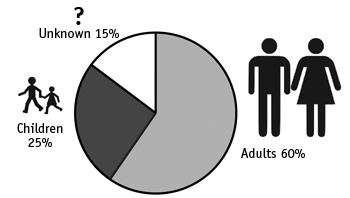

When looking only at civilian casualties for whom the age was known, children made up 43% of all casualties (1,066 of 2,497).[15] The vast majority of child casualties were boys (73%); 18% were girls.[16] In 25 states/areas, children made up half or more of civilian casualties for whom the age was known, more than double the number of states/areas where children were the majority in 2009.[17] States with the largest number of child casualties were Afghanistan (469 or 53%), Cambodia (80 or 31%), Sudan (74 or 58%), and Lao PDR (67 or 57%).

Overall, children made up 30% of all casualties for whom the age was known (1,066 of 3,564)—an increase in absolute terms from the 1,001 recorded in 2009 and similar as a proportion of all casualties in 2009.[18] For 85% of all casualties, information about their age was known (627 unknown), which was an increase from 80% in 2009 and an improvement in the age disaggregation of casualty data as called for by the Mine Ban Treaty’s Cartagena Action Plan.

Mine/ERW casualties by age: 2010

Items causing casualties

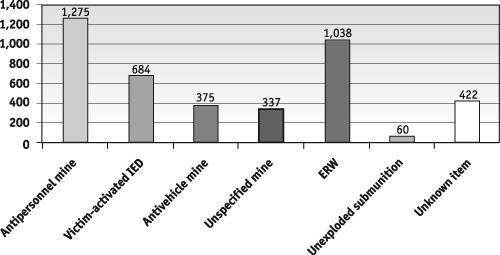

In 2010, antipersonnel mines, including victim-activated IEDs which are regarded as antipersonnel mines under the Mine Ban Treaty, caused the majority of casualties (52% or 1,959 of 3,769)[19] for which the type of explosive item was known.[20] For 3,769 casualties, or 90% of all recorded casualties, the item type that caused the casualty was known.[21] Of these:

- Mines, including antipersonnel mines, victim-activated IEDs, antivehicle mines, and mines of unspecified

type, were the most common at 2,671 (71% of the 2010 total)—an increase as compared to 2009:[22]- antipersonnel mines caused 1,275 casualties (34% of the 2010 total), an increase as compared with recent years;[23]

- victim-activated IEDs, or de facto antipersonnel mines, caused 684 casualties (18% of the 2010 total), the same percentage as recorded in 2009 but a significant increase from previous years;

- antivehicle mines caused 375 casualties (10% of the 2010 total), a slight increase from 2009; and

- mines of unspecified type caused 337 casualties (9% of the 2010 total).[24]

- ERW, including cluster munition remnants, caused 1,098 (29% of the 2010 total), a decrease compared to 38% in 2009:

Casualties by item: 2010

The most significant change in items causing casualties in 2010 was the increase in the number and percentage of casualties caused by antipersonnel mines. While this is largely due to the reclassification of casualty data in Colombia to include most casualties in this category, rather than as causalties by unknown explosive items, there was an overall increase in antipersonnel mine casualties in other states and areas.

There was also a continued increase in casualties from victim-activated IEDs, which function as de facto antipersonnel mines. Most victim-activated IED casualties were civilians (almost 70%). The two states with the highest numbers of casualties from victim-activated IEDs both saw increases in 2010: Afghanistan from 293 to 383 casualties and Pakistan from 190 to 203 casualties.[27] As in 2009, Afghanistan continued to account for the majority of casualties from victim-activated IEDs with 56% of the total in 2010. There was also an increase in the number of states and areas reporting these casualties from eight to 10.[28]

As in previous years, most casualties from antipersonnel mines, including victim-activated IEDs, were adults while children were the majority of casualties caused by ERW. In 2010, among antipersonnel mine casualties for which the age was known, 89% were adults and of these nearly all were men and 3% were women.[29] Antipersonnel mines caused 69% (or 91 of 131) of all demining casualties and 53% of military casualties (444 of 831). Among casualties caused by victim-activated IEDs, 80% were adults and, of these, most were males and 12% were female.[30] A quarter of all military casualties were caused by victim-activated IEDs.

In 2010 children constituted 59% of casualties caused by ERW where the age was known (597 of 1,015) compared to 61% in 2009; and 45% of the casualties were caused by unexploded submunitions.[31] Among those ERW casualties for whom both age and sex were known,[32] boys made up the single largest casualty group, as in 2009, with 48% or 465 of 968 of those reported. Some 34% of ERW casualties were men, 12% were girls, and 6% were women.

States/areas with casualties, by item type where known*

|

Item type |

State/area with casualties in 2009 |

|

Antipersonnel mines |

Afghanistan, Angola, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, DRC, Georgia, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kenya, Kuwait, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Panama, Russia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Yemen, Abkhazia, Somaliland, Western Sahara |

|

Antivehicle mines |

Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, BiH, Cambodia, Jordan, Lebanon, Myanmar, Niger, Pakistan, Senegal, Sudan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Somaliland, Western Sahara |

|

Unspecified mine type (antipersonnel or antivehicle) |

Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Mozambique, Pakistan, Russia, Turkey, Yemen, Western Sahara |

|

ERW |

Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Belarus, Cambodia, Colombia, DRC, Egypt, Eritrea, Georgia, Germany, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Niger, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Vietnam, Yemen, Zimbabwe, Abkhazia, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Palestine, Somaliland, Western Sahara |

|

Unexploded Submunitions |

Afghanistan, Cambodia, DRC, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon Vietnam, Nagorno-Karabakh, Western Sahara |

|

Victim-activated IEDs |

Afghanistan, Colombia, India, Iraq, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, Yemen |

Note: Other areas are indicated by italics.

* While the specific number of victim-activated IED casualties in Colombia and Myanmar is not known, there were known to have been some. Casualties from unexploded submunitions were recorded in Libya for the first time in 2011, outside the reporting period for casualty data collection for Landmine Monitor 2011.

Victim Assistance

Introduction

Victim assistance in 2010 benefited from a reoriented focus on service accessibility, availability, and some early efforts in a few states to combine the implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and the Convention on Cluster Munitions. However, these improvements were at least in part offset by increases in armed violence that eroded accessibility and availability of services in several states with significant numbers of mine/ERW survivors.

Overall, slow progress was made by states in turning the vital promises of the Mine Ban Treaty and the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 into progress in the lives of survivors on the ground. Yet despite irregular funding and challenges in sustainability, most victim assistance programs managed to hold their own and continued to provide much needed assistance to their beneficiaries.

In the first year implementing the Cartagena Action Plan, States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty mostly maintained existing coordination mechanisms and national victim assistance plans and, in a limited number of countries, began to address gaps in services in remote and rural areas. As the aspect of mine action that had been most neglected prior to the Second Review Conference in December 2009 and the area with the greatest potential to have a positive impact in the daily lives of survivors, increasing access to these services was a key action within the Cartagena Action Plan. However, the impact from the actions to provide appropriate services where and when survivors needed them was yet to reach most survivors. While the vast majority of survivors experienced little benefit during 2010 despite these activities, in some cases groundwork was laid for future progress.

The second major theme of 2010 was promoting the effective—and coordinated—implementation of victim assistance obligations and broader obligations to support persons with disabilities, across the Mine Ban Treaty, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and the CRPD in those cases where states were parties to two or more of these complementary conventions. Overall, most efforts in this area could be seen on paper, through reporting and planning, rather than in the lives of survivors. In some cases, however, the potential to combine resources and energies made some projects to benefit survivors seem more possible, especially in an environment of ever-tightening funding.

These two positive developments were clouded in many states and areas throughout 2010, and increasingly into 2011, by the challenges and obstacles to service provision that come with increased armed violence.

In this reporting period, the Monitor examined all mine and ERW-affected states and areas with mine/ERW survivors, identifying casualties in 60 states and areas,[33] and profiled changes and developments in victim assistance in 41 states and areas.[34] Of the 41 states and areas profiled, 25 are States Parties to the Mine Ban

Treaty.[35] Of the remaining 16 states and areas, 14 had not yet joined the Mine Ban Treaty and another two were areas that were ineligible to join international conventions.[36]

The Monitor measured progress in victim assistance in 2010 in four key areas that correspond to the victim assistance obligations included in the Mine Ban Treaty and its Cartagena Action Plan, which are also consistent with the Convention on Cluster Munitions and its Vientiane Action Plan:

- Victim assistance needs assessments: The completeness of information on mine/ERW casualties, the needs of survivors, and existing services is essential to planning and implementing an effective victim assistance program that addresses survivors’ real needs.

- Victim assistance coordination: This includes the planning, monitoring, and coordination of all aspects of victim assistance, with all relevant stakeholders, such as government ministries, survivors and their representative organizations, and civil society actors, and facilitated by a focal point with sufficient authority and resources to carry out the task.

- Survivor inclusion: The full participation of survivors and their representative organizations in all aspects of the Mine Ban Treaty (and other relevant legal mechanisms) and in all aspects of victim assistance decision-making, coordination, implementation, and monitoring is both their right and an important way to ensure the effectiveness of victim assistance.

- Accessibility, availability, and quality of services: Overcoming the lack of availability and the inaccessibility of appropriate services (including emergency and continuing medical care, physical rehabilitation, psychological support, and social and economic inclusion), particularly in rural and remote areas where many survivors are based, was a central action point in both the Cartagena Action Plan and the Vientiane Action Plan.

The Monitor also reviewed national policies and international legal frameworks designed to address the four key areas mentioned above, looking at ways in which different frameworks were harmonized and how they considered specific age and gender appropriate needs of survivors, guaranteed their human rights and prevented discrimination among mine/ERW survivors or between survivors and other persons with disabilities.

Assessing survivors' needs

Recognizing that data collection had presented severe ongoing challenges to providing adequate and appropriate victim assistance, under the Cartagena Action Plan, States Parties committed to “Collect all necessary data, disaggregated by sex and age, in order to develop, implement, monitor and evaluate adequate national policies, plans and legal frameworks”[37] and to be sure that such data includes information on both the needs of survivors and the availability of relevant services. This action also calls for “such data [to be made] available to all relevant stakeholders and that it contribute to other relevant, national data collection systems.”[38]

Progress in needs assessment was reported in 2010. Although data collection was not uniform or consistent, reporting indicated that information was disaggregated by sex and age in nearly every country with an official system for data collection.[39] Five States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty conducted assessments of mine/ERW survivors needs in 2010:

- In Angola, the national demining commission began a national victim survey and needs assessment in two of 18 provinces to identify and register mine and cluster munition survivors with disabilities and promote their socio-economic inclusion.

- In Chad, survivors were surveyed in the most mine/ERW-affected areas of the country to develop a national victim assistance plan. However, there was still a lack of data available to determine the scope of victim assistance needs and the information collected had not been made available to service providers.

- The DRC also carried out a national needs assessment of mine/ERW survivors in the most mine/ERW affected areas of the country through NGOs and service providers to inform the national victim assistance plan.

- Although there were no large-scale efforts to collect data on the needs of mine/ERW survivors in El Salvador, the government increased efforts to identify and register mine/ERW survivors, along with others disabled by war, including specific information about economic inclusion needs in order to develop its 2010 five-year strategic plan.

- Peru, together with NGO partners, continued to assess the needs of all survivors; and had interviewed and designed individualized social and economic reintegration plans for 70% of registered survivors by the end of 2010.

In addition, in Colombia, registering those victim assistance services provided to survivors within the national Epidemiological Monitoring System became obligatory throughout Antioquia, one of the departments with the great number of mine survivors, though this had not been replicated on a national scale. Similarly, Uganda conducted a second pilot of the national casualty surveillance system following an initial pilot in 2008. NGOs also carried out survivor needs assessments in one district of western Uganda in 2010 and the mine action center used the information to design their program.

Several States Parties used the information from past surveys. BiH (2009), Senegal (2009), Sudan (2009), and Tajikistan (2008) relied on previous assessments, while Albania and Thailand continued to update earlier data in the most affected areas. Iraq began to implement a needs assessment through its health care sector in 2011. However, half of the States Parties profiled did not carry out needs assessments in 2010 and had not reported using or sharing such information to plan or improve the provision of victim assistance services to mine/ERW survivors.[40]

Among states not parties, limited needs assessments were reported in Azerbaijan, Georgia, Lao PDR, Lebanon, in two regions of South Sudan, and in Sri Lanka. Data from previous surveys was used in Egypt (2008) and Iran (2009). No needs assessment or assessment-based planning was reported for six of the 11 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty profiled, all of them countries with high numbers of survivors: India, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Somalia, and Vietnam.

Additionally, numerous NGOs and service providers continued to collect data on survivors’ needs and the services they had received. In several countries and areas, service providers reported ongoing collection of data on beneficiaries’ needs.[41]

Victim assistance coordination

The Cartagena Action Plan underscored the importance of coordination and planning of victim assistance calling on States Parties to: “Establish, if they have not yet done so, an inter-ministerial/inter-sectoral coordination mechanism for the development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of relevant national policies, plans and legal frameworks….”[42]

Focal points and coordination mechansims

In 2010, 24 of the 25 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty profiled had victim assistance focal points; only Turkey had no focal point, but its national disability administration under the president was identified as the key body for victim assistance in 2011.[43] In two States Parties, the government focal point changed in 2010, while all others remained the same as in 2009. In the DRC, the focal point was changed from the Ministry of Health to the Ministry of Social Affairs, which was also the ministry responsible for coordinating all issues related to persons with disabilities and victims of conflict.[44] The change was seen as an improvement, moving government victim assistance responsibilities to a more appropriate ministry.[45] In Serbia, after more than a year of inactivity on victim assistance coordination by a state-run rehabilitation hospital, a new individual was named as the focal point within the hospital in the second half of 2010.

Among states not parties, seven states and one area had victim assistance focal points.[46] Of these, Lao PDR and Lebanon, as States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, were required to designate a government focal point for victim assistance in 2010; both chose the previously existing focal point from the mine action sector. India had no victim assistance focal point but did have a focal point for disability issues that was known to have included mine survivors. Six other states not parties and one area profiled had no victim assistance focal point.[47]

Among States Parties, three national victim assistance coordination mechanisms were established or began functioning in 2010 and one ceased to function. In total, at least 16 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty had functional national victim assistance coordination mechanisms during the year.[48]

- In Cambodia, the National Disability Coordination Committee (NDCC) replaced the Steering Committee for Landmine Victim Assistance and was tasked with monitoring the implementation of the National Plan of Action for Persons with Disabilities, Including Landmine/ERW Survivors 2009–2011.

- In Colombia, the Presidential Program for Mine Action convened the first meeting of the National Roundtable on Victim Assistance in June 2010 with the purpose of developing a national victim assistance plan.

- Croatia began multi-stakeholder victim assistance coordination in 2010 with regular meetings held during the year. The establishment of an official coordination body was announced in early 2011, formalizing the coordination structure begun in 2010.[49]

Yemen’s national coordinating mechanism, the Victim Assistance Advisory Committee, became inactive in 2010. In northern Iraq, there was a victim assistance coordinating mechanism facilitated by UNDP, but there was no corresponding national body for the rest of Iraq.

In early 2011, Burundi and the DRC both launched national coordinating mechanisms. In Burundi, the Interministerial Coordinating Committee for Victim Assistance convened victim assistance stakeholders in January 2011 for its first national victim assistance planning meeting.[50] In the DRC, the Interministerial Coordinating Committee for Victim Assistance, chaired by the Ministry of Social Affairs, held its first meeting in March 2011; this coordination mechanism remained dependent on support from UNDP.

Among states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, Azerbaijan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, South Sudan, and Vietnam had national victim assistance coordinating mechanisms during 2010. In post-independence South Sudan, the Victim Assistance Working Group remained active and effective though it continued to rely on support from the UN Mine Action Service. In Vietnam, a non-governmental stakeholders’ working group on mine issues was a forum to discuss the coordination of victim assistance activities. In Georgia, the Explosive Remnants of War Coordination Centre ceased to have a role in victim assistance coordination in early 2011.

In 2010, while there were some changes in which states and areas had functioning national victim assistance coordination, the total number remained very much the same as in 2009, at some 19 states.[51] However, as in previous years, the regularity and effectiveness of this coordination and the degree to which it was integrated into or harmonized with broader disability frameworks varied among the coordination mechanisms. There were improvements to coordination identified during the year, though there were also countries profiled in which the level of coordination activity was significantly reduced, decreasing effectiveness.

Decentralization of victim assistance coordination allowed for increased involvement from local authorities and survivors in locations where many survivors were based in both Angola and El Salvador.

- In Angola, workshops were held in four provinces with provincial office representatives and other governmental and nongovernmental victim assistance stakeholders to improve victim assistance planning and implementation at the provincial level. [52]

- In El Salvador, the state fund for people injured or disabled in conflict opened two regional offices as part of its decentralization campaign. The fund also held consultations in various regions of the country to familiarize and connect eligible people, including mine/ERW survivors, with the funds’ ser vices.[53]

In at least three cases, initiatives to integrate or transform victim assistance coordination into coordination for the broader disability sector were deepened in 2010.[54]

- In Afghanistan, where victim assistance coordination was included in broader disability coordination mechanisms, the Inter-ministerial Task Force on Disability was established to improve coordination between relevant ministries;[55]

- In Cambodia, the newly established NDCC, which includes victim assistance stakeholders, began its work in 2010. During the year, the NDCC strengthened and promoted its role in monitoring the implementation of the National Plan of Action for Persons with Disabilities, Including Landmine/ERW Survivors 2009–2011.

- In Mozambique, to ensure the inclusion of mine/ERW survivors and their perspectives in broader disability coordination, the victim assistance focal point as well as survivors participated in the 2010 review of the five-year national disability plan.

In at least three states, activities to coordinate victim assistance were reduced in 2010, as compared with 2009. In Yemen, as mentioned above, the Victim Assistance Advisory Committee ceased to function in 2010. In Uganda, the Victim Assistance Forum, which had been established in 2009, held just one meeting in 2010 due to a lack of funding; budget cuts in January 2011 further limited support for the activities of the Forum. In Lebanon, the National Steering Committee on Victim Assistance reduced its frequency of meetings during the year due to decreased funding levels. This was seen to have decreased the efficiency of victim assistance planning.[56]

Development of national plans

In 2010, at least 13 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty had active victim assistance or broader disability plans that explicitly included mine/ERW survivors.[57] Another two plans were developed during the year and Mozambique and Uganda developed follow-up plans. Two states, Burundi and Chad, began developing victim assistance plans for the first time in 2010. In addition, El Salvador reported having a national victim assistance plan based on the Cartagena Action Plan, but no efforts to implement or monitor the plan in 2010 could be identified.

- Croatia’s “Action Plan of Assistance to Mine and UXO Survivors 2010–2014” was developed by the newly formed inter-ministerial victim assistance coordination group, including survivors’ representative organizations. The plan was approved by the victim assistance coordination body in February 2011 and was awaiting government endorsement as of June 2011.

- The DRC’s annual national plan for victim assistance and persons with disabilities (November 2010–October 2011) was developed based on the Cartagena Action Plan and the results of a 2010 survivor needs assessment. As of June 2011, the plan had not yet been approved.[58]

- In Mozambique, a new five-year National Disability Plan, inclusive of survivors, was under development in 2010, to come into effect in 2011.

In 2010, Uganda published a new Comprehensive Plan of Action on Victim Assistance 2010–2014. Objectives from the previous 2008–2012 plan were reviewed and aligned to relevant national policies as well as to international legal mechanisms such as the Cartagena Action Plan, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and the CRPD.[59]

In contrast to the planning efforts of States Parties, among the 16 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, just two, Azerbaijan and South Sudan had victim assistance plans in 2010. Throughout 2010, victim assistance in South Sudan continued to be implemented based on the plan for Sudan, a Mine Ban Treaty State Party.[60] Lao PDR and Lebanon, both States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, reported on the development of national victim assistance plans in 2010 though neither had finalized a plan as of 1 September 2011. Nepal had previously reported having a victim assistance plan, but it was inactive in 2010. India had a disability plan that was said to include mine/ERW survivors.

Monitoring national plans

Numerous victim assistance coordinating mechanisms included within their functions the monitoring of the implementation of victim assistance and/or disability plans. However, among all 41 countries profiled, of which at least 17 had plans during 2010, just two countries, Mozambique and Uganda, where new plans were being developed, reported comprehensive efforts to monitor and evaluate their implementation.

Survivor inclusion

States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, through subsequent action plans, have made it clear that mine survivors, their families, and representative organizations should not just be recipients of assistance but active participants in all aspects of treaty implementation. Through the Cartagena Action Plan, States Parties committed to ensure the continued involvement and effective contribution of experts, including mine survivors, in their delegations.[61]

In 2010, there were some improvements on the part of states to track and share information about this inclusion. Statements made by Sudan and Uganda at the Tenth Meeting of States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty in Geneva in December 2010 and at the Mine Ban Treaty intersessional meetings in Geneva in June 2011 noted progress was made in the inclusion of survivors and their representative organizations in victim assistance. At the intersessional meetings, Colombia spoke on their efforts to increase survivor participation in planning and service provision. South Sudan reported on the involvement of disabled persons organizations in implementing victim assistance and called for funding to support the development of survivors associations.[62] However, in most cases, monitoring survivor inclusion remained difficult, particularly at the national level—the level at which survivors have the greatest impact on victim assistance.

In 2010, just four States Parties—BiH, Peru, Tajikistan, and Thailand—included a mine/ERW survivor or other person with a disability in their delegations to the intersessional Standing Committee meetings or the Tenth Meeting of States Parties. This is a reduction from the seven identified in 2009.

At the national level, in 2010, 21 profiled States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty included mine/ERW survivors, or their representative organizations, in victim assistance coordination. This includes all 16 States Parties with functioning victim assistance coordination mechanisms as well as five other states in which survivors participated in ad hoc planning meetings or within broader disability coordination structures.[63] However, in eight of the 21 states, this participation was seen to be limited, often in terms of the ability of survivors to contribute to decision-making.[64]

- In Angola, survivors’ associations and disabled persons organizations were invited to provincial victim assistance coordination meetings, but felt that the meetings were used for the dissemination of information only and that survivors and other persons with disabilities were not included in decision-making.

- In Colombia, the survivors who participated in planning meetings changed from one meeting to the next, limiting their ability to follow important decisions.

- Croatia reported that survivor inclusion in drafting action plans or implementing victim assistance was “variable” and often a “tokenism.”[65]

In general, the quality of survivor participation varied, often in correlation with the effectiveness of the coordinating mechanism itself.

Just five states not parties included survivors in victim assistance coordination in 2010 and this again included South Sudan, which remained part of Sudan throughout the year.[66] Lao PDR and Lebanon, two of the five, were obligated to include survivors through their commitments under the Convention on Cluster Munitions. In addition, India included survivors in the drafting of disability policy.

In 23 of 25 States Parties profiled, survivors were involved in the implementation of victim assistance.[67] Only in Turkey did survivors report that they were not involved in the implementation of services relevant to their needs; there was no information available regarding survivor inclusion from Eritrea. As in previous years, most often this participation was through NGOs, survivor’s associations, or international organizations, such as the ICRC.[68] However, in at least one case, Senegal reported on its efforts to build the capacity of survivors through management courses. In states where survivors were included in the implementation of victim assistance, it was not necessarily systematic or widespread.

Survivor inclusion in the implementation of victim assistance was identified in six states not parties as well as one area.[69]

Survivors were most often active in peer support, social inclusion, and advocacy on survivors’ rights, but in several states they were also active in the fields of physical rehabilitation and economic inclusion.[70] In these cases however, survivors were implementing services through NGOs or international organizations, rather than state bodies. In Angola, Chad, DRC, and Peru, survivors were involved in data collection and in assessing the needs of survivors. In Peru, survivor data collectors also worked with survivors to design individualized economic inclusion programs.

Quality and accessibility of services

A central theme of The Cartagena Action Plan is ensuring that victim assistance has a tangible impact on the daily lives of survivors. In Cartagena, States Parties agreed to dedicate efforts to improving the availability, accessibility, and quality of services by removing “physical, social, cultural, economic, political, and other barriers, including by expanding quality services in rural and remote areas and paying particular attention to vulnerable groups.”[71]

Availability

General increases in the availability of victim assistance services were identified in just three States Parties profiled. In Senegal and Thailand, increasing resources and attention dedicated to victim assistance increased the availability of a range of services, including physical rehabilitation and economic inclusion. In Mozambique, there was a slight increase in the availability of services as a result of an increased focus on disability. No States Parties reported a general decrease in the availability of all types of victim assistance.

Yemen saw an increase in emergency medical attention, largely as a result of the increased demand for such services following the increase in armed violence.

In Afghanistan, Chad, Colombia, and El Salvador, there were increases in the availability of physical rehabilitation; in all cases this was closer to where survivors were based. In Uganda, the availability increased in the western region of the country while declining in the north. At the same time, the availability of physical rehabilitation decreased in Albania, Angola, Cambodia, and Sudan due to a lack of dedicated government resources, in most cases following a transition to national management.

In Peru and Sudan, there was an increase in economic inclusion opportunities for survivors, while such opportunities decreased in Ethiopia. In Afghanistan and Albania, the availability of psychological support, including peer support, decreased during the year.

Among states not parties, increases in the availability of victim assistance were identified in five states. In Azerbaijan and Vietnam, these increases were mainly the result of greater investment in disability services, while in Egypt the increases targeted mine/ERW survivors. In Pakistan, medical attention and physical rehabilitation services increased as a result of an increased demand following an upsurge in violence. In Nepal, there was an increase in economic inclusion opportunities.

Accessibility

Recognizing the importance of improving accessibility to the physical environment, existing services, communications, and information as inextricably linked to improving access to victim assistance services, the co-chairs of the Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration dedicated the victim assistance parallel program at the June 2011 intersessional meetings to the topic. Civil society experts and representatives of States Parties shared experiences on accessibility challenges and ways to advance the Cartagena Action Plan through improved accessibility.

During 2010, actions were taken in nine States Parties profiled to improve accessibility for survivors and other persons with disabilities. In Ethiopia, Tajikistan, and Uganda, laws or guidelines on accessibility passed during the year were designed to increase access to public spaces, including sidewalks and public buildings. By the end of the year, in Ethiopia, there was evidence that the accessibility proclamation was being enforced. In Afghanistan, the survivors’ association made some 50 buildings accessible during the year and organized a multi-stakeholder conference to promote physical accessibility and peer support. As a result of the workshop, the ministry responsible for disability issues organized a training meeting in accessibility for all provincial mayors.[72] In Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Peru, and Thailand, steps were taken to decentralize health and physical rehabilitation services outside of capitals and strengthen community-based rehabilitation as a means to increase access in remote and rural areas where many survivors live. In Serbia, survivors perceived there to be a small improvement in access to services as a result of civil society efforts to increase awareness among survivors about their rights. However, not all of these efforts had an immediate impact in improving survivors’ ability to access services.

In contrast, among states not parties, improvements in access to services were only identified in Vietnam which implemented numerous programs for persons with disabilities that also benefited mine/ERW survivors, while access decreased due to environmental factors, such as increased violence and natural disasters, in India, Pakistan, Somalia, and South Sudan.

Quality

While some 15 States Parties reported having undertaken activities to develop and/or implement capacity-building and training plans for victim assistance during 2010,[73] improvements in the quality of victim assistance were only identified in four States Parties profiled. In BiH, training in physical rehabilitation, economic inclusion, and peer support improved the quality of activities in these areas. In El Salvador, increased national funding for victim assistance improved the quality of nearly all services, but especially physical rehabilitation and economic inclusion programs. In Eritrea, improvements in quality were seen as a result of the community-based rehabilitation program. Tajikistan saw small improvements as a result of ongoing efforts to implement the national victim assistance plan. Outside of these four states, in Ethiopia there were some small improvements in the quality of physical rehabilitation while this declined in Angola.

Among states not parties, improvements to the quality of victim assistance were only identified in Vietnam. However, it is worth noting that while some states not parties saw declines in the accessibility and/or availability of services, there were no states or areas where there was reporting of an overall worsening in the basic quality of victim assistance, despite numerous reports of decreased funding available for victim assistance.

Sustaining peace and rebuilding a country in the midst of conflict or emerging from conflict or post-conflict have a significant impact on States Parties’ abilities to meet victim assistance commitments under the Mine Ban Treaty. As was clear in 2010, increasing violence in several of the profiled States Parties undercut efforts to improve access and availability of victim assistance by increasing the need for emergency medical care and physical rehabilitation services, further taxing available services, and by preventing survivors from traveling to services. Service providers, such as the ICRC as well as other international and national organizations, also reported limiting their areas of service, thus inhibiting access to survivors in conflict-affected areas. Ongoing violence also prevented the rebuilding of health centers and other vital services that had been destroyed or degraded by conflict.

In at least six States Parties, the security situation had a direct impact on access to services. In Iraq, where there was decreased armed violence, access to services increased as survivors were able to move around the country with reduced threats to their safety. In some cases services did not have the capacity to keep up the new demand. Conversely, in Afghanistan, Chad, Senegal, Sudan (South Sudan), and Yemen a deteriorating security situation decreased access to services, preventing travel and limiting the availability of mobile outreach services. The same occurred in states not parties India, Pakistan, and Somalia.

Improved security conditions provide opportunities for states to rebuild with the support of the international community. By considering survivors in post-conflict development plans, victim assistance obligations can be met as part of a wider effort to develop health and rehabilitation services, especially in rural areas, or by including survivors and other persons with disabilities in job creation programs and other income generating projects.

International legislation and policies

The Cartagena Action Plan calls for a holistic and integrated approach to victim assistance that is both age and gender sensitive and in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law. Other international mechanisms with relevance to victim assistance include the CRPD, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and other frameworks such as the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW).

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

In the Mine Ban Treaty context, the CRPD is considered to “provide the States Parties with a more systematic, sustainable, gender sensitive and human rights based approach by bringing victim assistance into the broader context of persons with disabilities.”[74] The Cartagena Action Plan often refers to a rights-based approach to assistance. At an international level, to August 2011, the CRPD has remained a key focus of victim assistance discussions. During the intersessional meeting of the Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration in June 2010, the Chair of the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities presented on possible synergies in the implementation of the CRPD and the Mine Ban Treaty’s victim assistance obligations. Using the cooperation provisions of the CRPD was a central theme of the Tirana “International Symposium on Cooperation in the Pursuit of the Victim Assistance Aims of the Antipersonnel Mine Ban Convention” which was held in the framework of the newly formed Standing Committee on Resources, Cooperation and Assistance in April 2011. While supportive of and interested in seeing the coordinated implementation of both conventions benefit survivors and other persons with disabilities, the ICBL has noted that synergies between victim assistance obligations and CRPD obligations require efforts on both fronts and cautioned that mainstreaming without the championing of assistance for mine/ERW victims will likely lead to some victim assistance obligations not being fulfilled.[75]

Of the 39 states[76] with victim assistance profiles for 2010, 21 had ratified the CRPD by 1 August 2011, including 14 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty (four of these ratified the CRPD in 2010 or 2011 through August).[77] Another seven states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty had ratified the CRPD by 1 August 2011.[78] Also among those countries profiled, another five Mine Ban Treaty States Parties[79] and four states not parties had signed, but not yet ratified, the treaty as of 1 August 2011.[80] As of 15 September 2011, Afghanistan was preparing to finalize and deposit its ratification of the CRPD.[81]

Convention on Cluster Munitions

The Convention on Cluster Munitions ensures the full realization of rights of all persons in communities affected by cluster munitions by obligating states to adequately provide assistance, without discriminating between people affected by cluster munitions and those who have suffered injuries or disabilities from other causes. The principles of the convention’s Vientiane Action Plan mirror most of those of the Mine Ban Treaty Cartagena Action Plan, but unlike the Mine Ban Treaty Plan, the Vientiane Action Plan contains a range of concrete timeframes for actions. As of 1 August 2011, four profiled Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with cluster munition victims had ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[82] Afghanistan ratified in September 2011. Another eight had signed, but not yet ratified, the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[83]

Convention on Conventional WeaponsThe Plan of Action on Victim Assistance under CCW Protocol V on explosive remnants of war, adopted on 11 November 2008, contains similar provisions to the Cartagena Action Plan and the Convention on Cluster Munitions on victim assistance though without the specific and time-bound obligations for States Parties. As of 15 September, six profiled States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty and three states not parties were party to the protocol.[84] Of these nine,[85] in 2010, Pakistan used its Article 10 report to provide information about victim assistance, stating that the Military Operations Directorate of the Pakistan Army was the victim assistance focal point but not providing any other details about available victim assistance.[86] Victim assistance was also mentioned in Croatia’s transparency report as required under the protocol.[87] BiH reported on mine casualties recorded in 2010, but not on victim assistance.[88] This is in line with other years when reporting on victim assistance in ERW-affected countries under Protocol V has been intermittent, inconsistent, and incomplete. However in the past, this reporting has sometimes presented otherwise unavailable insights into victim assistance for previously profiled states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty such as Georgia and Russia.

Cross-convention synergies

In 2010, for the first time, it was possible to identify Mine Ban Treaty States Parties harmonizing their efforts to implement the Mine Ban Treaty, CRPD, and the Convention on Cluster Munitions across all three conventions, at the national and diplomatic levels. With these early efforts, it is too soon to say whether or not these harmonized efforts have raised the standards of victim assistance for States Parties, as they should, or whether there will be a direct link with a consequent improvement in the daily lives of survivors. Identifying these synergies as they develop should enable the international community to monitor their impact in future years. Each of the three conventions provides useful strategies and priorities for providing comprehensive care and promoting the full realization of human rights for all survivors and persons with disabilities. To ensure the full rights of survivors, it is imperative that all countries apply the highest possible standard set by a convention.

In at least three states, steps taken to implement the CRPD in 2010 had the potential to impact mine/ERW survivors as well. For example, in Ethiopia efforts to improve accessibility and employment of persons with disabilities including mine survivors were linked with CRPD implementation. In Mozambique, the creation of the National Disability Council and the revision of the national disability plan have been undertaken as a means to implement the CRPD. Thailand strongly connected its work on victim assistance with the implementation of its obligations under the CRPD, by including the registration of survivors within a broader disability register to ensure access to pensions and other benefits.

Some states have also begun to coordinate their implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions with their efforts under the Mine Ban Treaty. As of 1 August 2011, all States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty which had designated a victim assistance focal point under Article 5 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions had chosen the same focal point that is active under the Mine Ban Treaty. BiH, Croatia, and Iraq presented basically the same information on progress and challenges in providing victim assistance at the Mine Ban Treaty and Convention on Cluster Munitions intersessional meetings in June 2011. The DRC did the same in preparing transparency reporting for both conventions.

Finally, a handful of states have begun to consider all three conventions together when planning the provision of services and the development of policies. For example, in 2010, Croatia and Uganda both considered common obligations within all three conventions as well as obligations that were specific to each in developing national victim assistance/disability plans. Other consolidated actions could be possible, such as survivor needs assessments, Action 25 of the Cartagena Action Plan and a time-bound action with the Vientiane Action Plan, which might appropriately be combined with overall disability needs assessments, implemented under the CRPD, as long as survivors are included and questions capture their particular needs. While not yet a State Party to the CRPD, in early 2011 Iraq made the decision to combine a planned survivor needs assessment with a broader disability assessment being advanced by the Ministry of Health after being unable to secure sufficient funding for a stand-alone survivor assessment.

Promoting age and gender sensitive victim assistanceTaking age and gender into consideration is important to ensuring appropriate victim assistance services to fulfill the needs of all survivors and family members of those people injured and killed. For example, growing children require new prosthesis more often that adults, and children’s psychological, social and educational needs also vary. However, a year into the Cartagena Action Plan, states were not yet reporting on their efforts to address the specific needs of survivors according to their ages.

Only slightly more information was available regarding gender-sensitive services. Among States Parties, the DRC and Uganda had both held gender trainings for victim assistance stakeholders as of 1 August 2011. In Senegal, a new program to provide psychosocial support for female mine survivors was launched. In Ethiopia, employment regulations recognized that women with disabilities faced multiple barriers to gaining work. In El Salvador, the state fund for victims of conflict also provides social protection for family members of those killed. There was increasing recognition that services should take into account the differing needs of women, men, boys, and girls and that although the vast majority of mine survivors are male, the particular needs of female survivors and of women as secondary victims must be addressed.

Yet the principles of equality and non-discrimination were far from being fulfilled. For example, in Afghanistan and Tajikistan, there was a persistent disparity in services based on age and gender and in Yemen, the absence of female medical professionals prevented many women from seeking services. It is likely that there was age and/or gender discrimination in other States Parties from which information was not available.

[1] Figures include individuals killed or injured in incidents involving devices detonated by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person or a vehicle, such as all antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, abandoned explosive ordnance (AXO), unexploded ordnance (UXO), and victim-activated IEDs. AXO and UXO, including cluster munition remnants, are collectively referred to as ERW. Not included in the totals are: estimates of casualties where exact numbers were not given; incidents caused or reasonably suspected to have been caused by remote-detonated mines or IEDs (those that were not victim-activated); and people killed or injured while manufacturing or emplacing devices. In many states and areas, numerous casualties go unrecorded; thus, the true casualty figure is likely significantly higher.

[2] For more information specifically on casualties caused by cluster munitions, please see CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2011 (Ottawa: Mines Action Canada, October 2011), www.the-monitor.org.

[3] The 54 states and six areas where casualties were identified in 2010 are: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, Germany, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Malawi, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Senegal, Somalia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Vietnam, Yemen, and Zimbabwe, as well as Abkhazia, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Palestine, Somaliland, and Western Sahara.

[4] In 2010, the Monitor reported a total of 3,956 casualties for 2009. However, based on updated casualty data collected in 2011, this figure has been revised to 4,010.

[5] For 2010 data, all casualties occurring in both Sudan and South Sudan have been recorded as casualties in Sudan since South Sudan became independent in 2011.

[6] In Colombia, 229 fewer casualties were recorded in 2010 as compared to 2009, for a 31% overall decline.

[7] Seven countries with casualties in 2009 (Burundi, China, Cyprus, El Salvador, Mali, Syria, and Zambia) reported no casualties in 2010 and three countries (Germany, Malawi, and Panama) with casualties in 2010 did not record casualties in 2009.

[8] The category of “civilian casualties” did not include humanitarian clearance personnel, who are also civilians but were, as in previous years, recorded in a separate category for deminers, to ensure more detailed analysis.

[9] In 2009, the vast majority of military casualties were also recorded in the same three states: Afghanistan, Colombia, and Pakistan. In Colombia and Afghanistan, the number of military casualties declined in 2010 while the number increased significantly (from 103 to 186) in Pakistan.

[10] The term “deminer” is used here to refer to professional clearance operators clearing all kinds of explosive items including mines, unexploded submunitions, and other ERW.

[11] States/areas with casualties among deminers in 2010 are: Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Croatia, Ethiopia, Germany, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Mozambique, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Abkhazia.

[12] “WWII-era bomb explodes in Germany,” Al Jazeera, 2 June 2010, english.aljazeera.net.

[13] This was exactly the same division by sex as in 2009. The sex of 3,539 casualties was known and 652 casualties was unknown, 16% of the total compared to 23% for 2009, possibly indicating an increase in the disaggregation of casualty data by sex, as called for by the Mine Ban Treaty’s Cartagena Action Plan.

[14] States in which there was no sex disaggregation of casualty data (Armenia, Chad, Somalia, and Ukraine) have not been included in this total. The 25 states and areas that registered only male casualties all had relatively small numbers of casualties in 2010, with Russia with 23 casualties being the largest national total.

[15] Children are under the age of 18.

[16] The sex of 9% of child casualties was not recorded.

[17] States and areas with children as the majority of civilian casualties for which the age was known in 2010 were: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, DRC, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, India, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Lao PDR, Malawi, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Philippines, Sudan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Yemen, and Zimbabwe and Kosovo, Palestine, and Somaliland. Of the total, eight (Albania, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Malawi, Nicaragua, Philippines, Zimbabwe, and Kosovo) had five casualties or less.

[18] Children made up 32% of all casualties in 2009.

[19] This includes 505 of the 512 casualties identified in Colombia in 2010. While recorded as antipersonnel mines by the national mine action center, is it widely accepted that this figure includes casualties caused both by factory-made antipersonnel mines and by victim-activated IEDs that are antipersonnel mines but not factory-made.

[20] For all recorded casualties caused by victim-activated IEDs, the explosive item type has been considered as antipersonnel victim-activated IEDs in Monitor casualty data analysis because available information indicates that the fuze of nearly all victim-activated IEDs allows them to be activated by a person as well as a vehicle. It was not possible to distinguish between the types of victim-activated IEDs in casualty data as there is no clear means of determining the sensitivity of the fuze. Even excluding victim-activated IEDs, antipersonnel mines remain the cause of the largest number of casualties by explosive item type in 2010.

[21] For 422 casualties, the explosive item type was not known. A significant revaluation of the percentage of casualties for which the explosive item was unknown in 2009 was made in 2011. The change was largely due to the inclusion of Colombian casualties as casualties caused by antipersonnel mines (and/or de facto antipersonnel mines). Previously, these casualties had been included among those casualties for which the item was unknown because of uncertainty regarding the type of explosive items recorded. For updated data see Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, “Victim-activated IED Casualties,” Fact sheet, June 2011, www.the-monitor.org.. Of the 3,956 casualties identified in 2009, the type of explosive item was known for 3,692. In contrast, previously, in ICBL, Landmine Monitor 2010 (Ottawa: Mines Action Canada, October 2010), www.the-monitor.org, it had been reported that the item type was known for just 3,018 of the 3,956 casualties in 2009.

[22] The Monitor identified 2,548 casualties of mines for 2009; mines were defined to include antipersonnel mines, victim-activated IEDs, antivehicle mines, and mines of unspecified type. This constituted an adjustment from the way explosive items were differentiated in ICBL, Landmine Monitor 2010 (Ottawa: Mines Action Canada, October 2010), www.the-monitor.org. For updated data see Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, “Victim-activated IED Casualties,” Fact sheet, June 2011, www.the-monitor.org..

[23] Most of the increase in the number of antipersonnel mine casualties from 513 in 2009 can be attributed to the inclusion of Colombian antipersonnel mine casualties within this total. Including the casualties in Colombia, there would have been 1,187 antipersonnel mine casualties globally in 2009.

[24] Mines of unspecified types refers to reporting in which it is unclear if an explosive item is a mine or IED, if antipersonnel or antivehicle; it does not include command-detonated IEDs and mines.

[25] ERW including UXO and AXO, other than cluster munitions remnants.

[26] Much of this decrease can be attributed to a lack of casualty data disaggregated by explosive item type from Lao PDR, the country with the highest numbers of cluster munition casualties in recent years.

[27] Preliminary casualty data for 2011 showed still greater increases in victim-activated IED casualties in both Afghanistan and Pakistan as compared with 2010 and all other previous years.

[28] In 2010, victim-activated IED casualties were recorded in: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Turkey, Thailand, Iraq, India, Peru, Russia, and Yemen. No victim-activated IED casualties were identified in Russia, Thailand, Turkey, or Yemen in 2009. Victim-activated IED casualties were recorded in Cambodia and the DRC in 2009, but not in 2010.

[29] Based on information for 1,131 antipersonnel mine casualties. For 144 of the total 1,275 antipersonnel mine casualties (11%) the age was unknown.

[30] This excludes those casualties for which the age and sex was not known.

[31] Children made up 25 of 56 casualties for which the age of the casualty was known.

[32] The age, sex or both was not known for 70 of the 1,038 casualties recorded from other ERW.

[33] The 54 states and six areas where casualties were identified in 2010 are: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, Germany, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Malawi, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Senegal, Somalia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Vietnam, Yemen, Zimbabwe, as well as Abkhazia, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Palestine, Somaliland, and Western Sahara.

[34] Sudan and South Sudan have been profiled separately. While South Sudan was part of Sudan for most of the reporting period, information collected for 2010 will serve as a baseline for future reporting. Not all states and areas profiled registered casualties in 2010; some, such as El Salvador and Serbia, had significant numbers of survivors but no confirmed casualties during the year. The 41 states and areas profiled are: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, India, Iraq, Iran, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Vietnam, and Yemen, as well as Abkhazia and Western Sahara.

[35] The 25 states parties to the Mine Ban Treaty profiled were: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, and Yemen (States in bold had also signed or ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions as of 15 September 2011). Two others, Lao PDR and Lebanon, are States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and Somalia is a signatory to that convention.

[36] The 14 states profiled that remained outside the Mine Ban Treaty were: Azerbaijan, Egypt, Georgia, India, Iran, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Somalia, South Sudan (part of Sudan, a State Party, for much of the reporting period), Sri Lanka, and Vietnam, as well as the areas of Abkhazia and Western Sahara.

[37] “Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014: Ending the Suffering Caused by Anti-Personnel Mines,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 25, (hereafter referred to as the “Cartagena Action Plan”).

[38] “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 25.

[39] Disaggregated data for Chad and Somalia was not available at press time.

[40] Afghanistan, Algeria, Burundi, Cambodia, Croatia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Serbia, Turkey, and Yemen, as well as Colombia and Uganda which implemented limited or partial surveys.

[41] Such data collection occurred in several States Parties including: Afghanistan, Albania, Cambodia, El Salvador, Iraq, Mozambique, Serbia, Sudan and Uganda, but this list cannot be considered exhaustive as Monitor research did not explicitly request information about efforts by service providers to collect data on survivors’ needs.

[42] “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 24.

[43] The 24 States Parties with a victim assistance focal point in 2010 were: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uganda, and Yemen.

[44] Statement of the DRC, Tenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 1 December 2010.

[45] Interview with Jean Marie Kiadi Ntoto, Victim Assistance Officer, UN Mine Action Coordination Center (UNMACC), Kinshasa, 17 April 2011.

[46] States not parties and areas with victim assistance focal points: Azerbaijan, Egypt, Iran, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Nepal, South Sudan, and Abkhazia.

[47] States not parties and areas and areas without victim assistance focal points or disability focal points inclusive of survivors in 2010 were: Georgia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and Western Sahara.

[48] States Parties with national coordinating mechanisms in 2010 were: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Peru, Senegal, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Uganda. There was no functioning coordinating mechanism in: Algeria, Burundi, DRC, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Serbia, Turkey, and Yemen.

[49] Croatian Mine Action Center (CROMAC), “1st Coordination Meeting of State Administration Bodies and Non-Governmental Organizations in MVA Programmes Held,” 15 April, 2010, www.hcr.hr; CROMAC, “1st Meeting of MVA Coordination Held,” 3 February 2011, www.hcr.hr; and statement of Croatia, Tenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 1 December 2010.

[50] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Désiré Irambona, Coordinator, Humanitarian Department for Mine/UXO Action, 10 March 2011; and statement by Burundi, Tenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 1 December 2010.

[51] South Sudan has not been included in this total since it remained part of Sudan throughout 2010 though it did operate a separate coordination mechanism. Vietnam has also not been included since victim assistance coordination is not carried out by the government. There was also known to be victim assistance coordinating mechanisms in at least two states not profiled in 2010, Jordan and Guinea-Bissau, but with low but steady levels of activity.

[52] Interview with Nsimba Paxe, Victim Assistance Specialist, Inter-sectoral Commission on Demining and Humanitarian Assistance, Luanda, 16 June 2011.

[53] Interview with Marlon Mendoza, General Manager, Protection Fund, San Salvador, 3 March 2011.

[54] In the cases of Afghanistan and Cambodia, national disability plans were explicitly developed as part of efforts to implement the Mine Ban Treaty and its action plans, with the development process led by victim assistance stakeholders.

[55] Statement of Afghanistan, Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration, Geneva, 22 June 2010.

[56] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Khaled Yamout, Mine Risk Education/Victim Assistance Program Coordinator, Norwegian People’s Aid, 15 May 2011.

[57] State parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with active victim assistance plans in 2010 were: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Eritrea, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Uganda.

[58] Jean Marie Kiadi Ntoto, UNMACC, in Geneva, 20 June 2011.

[59] Statement of Uganda, Tenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 1 December 2010.

[60] As of June 2011, South Sudan expected to continue to develop victim assistance activities based on the components of the Sudanese victim assistance plan that were relevant to the situation in the newly independent country.

[61] “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 29.

[62] Ministry of Gender, Child and Social Welfare (MGCSW), “Victim Assistance Report Southern Sudan for the years 2010 and 2011. Southern Sudan Presentation, On States Party Meeting As From 20 To 24th June, 2011,” provided by Nathan Wojia Pitia Mono, Director General, MGCSW, in Geneva, 24 June 2011.

[63] States with survivor inclusion in coordination in 2010 were: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Uganda.

[64] States with limited survivor participation in coordination were: Angola, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, Iraq, and Uganda.

[65] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, (for the period 1 August 2010 to 1 January 2011), Form H.

[66] Azerbaijan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, South Sudan, and Vietnam.

[67] Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, , Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uganda, and Yemen.

[68] Most information on survivor inclusion in the implementation of services was provided by NGOs, not governments.

[69] Azerbaijan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Nepal, South Sudan, and Abkhazia. There was no information available regarding survivor inclusion in the implementation of victim assistance in Egypt, Iran, or Pakistan.

[70] Some examples of States Parties where survivors were involved in providing physical rehabilitation include: Afghanistan, DRC, El Salvador, and Iraq; and in economic inclusion activities include: BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, and Senegal.

[71] “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 31.

[72] ICBL-CMC, “Connecting the Dots Detailed Guidance Connections, Shared Elements and Cross-Cutting Action: Victim Assistance in the Mine Ban Treaty and the Convention on Cluster Munitions & in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,” Geneva, April 2011, p. 16.

[73] UN, “Achieving the aims of the Cartagena action plan: The Geneva progress report 2009–2010,” Geneva, 29 November–3 December 2010, APLC/MSP.10/2010/WP.8, 16 December 2010, p. 22.

[74] UN, “Cartagena Review Document,” Cartagena, 30 November–4 December 2009, APLC/CONF/2009/WP.2, 18 December 2009, pp. 54–55.

[75] Statement by ICBL, Standing Committee on Resources, Cooperation and Assistance, Geneva, 24 June 2011.

[76] Of the 41 states and areas profiled, two areas are not recognized by the UN and cannot join international conventions; therefore, they have not been included in this count.

[77] The Mine Ban Treaty States Parties profiled that have ratified the CRPD are: Algeria (2009), BiH (2010), Colombia (2011), Croatia (2007), El Salvador (2007), Ethiopia (2010), Peru (2008), Senegal (2010), Serbia (2009), Sudan (2009), Thailand (2008), Turkey (2009), Uganda (2008), and Yemen (2009).

[78] The states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty profiled in the Monitor that have ratified the CRPD are: Azerbaijan (2009), Egypt (2008), India (2007), Iran (2009), Lao PDR (2009), Nepal (2010), and Pakistan (2011).

[79] Albania, Cambodia, Burundi, Malta, and Mozambique.

[80] Georgia (2009), Lebanon (2007), Sri Lanka (2007), and Vietnam (2007).

[81] Email from the Afghanistan Disability Support Programme, UN Office for Project Services, 15 August 2011.

[82] Mine Ban Treaty States Parties: Albania, BiH, Croatia, and Mozambique. States not parties also profiled: Lao PDR and Lebanon.

[83] Mine Ban Treaty States Parties: Angola, Chad, Colombia, Republic of the Congo, DRC, Iraq, Peru, and Uganda. All except Colombia and Peru have cluster munition casualties.

[84] Mine Ban Treaty States Parties: Albania, BiH, Croatia, El Salvador, Peru, and Tajikistan. States not parties also profiled: Georgia, India, and Pakistan.

[85] Four of the ten, BiH, Croatia, India, and Pakistan submitted Article 10 reports for 2010. India indicated that victim assistance for ERW survivors in India was not relevant.

[86] Pakistan, CCW Protocol V Article 10 Report, 15 March 2011, Form C.

[87] Croatia, CCW Protocol V Article 10 Report, (for calendar year 2010), March 2011, Form C.

[88] BiH, CCW Protocol V Article 10 Report, 31 March 2011, Form C.